Cognitive Analytic Therapy - its influence on my practice in the Occupational Health Speciality within a Clinical Psychology and Counselling Service

Appleby, K., 2003. Cognitive Analytic Therapy - its influence on my practice in the Occupational Health Speciality within a Clinical Psychology and Counselling Service. Reformulation, Spring, pp.18-24.

Karen Appleby

Introduction to the service

The Occupational Health Psychology speciality provides a range of services to NHS and other staff groups, The main aspects of the service are individual assessment and therapy; training; and consultancy to managers or groups of staff. The service is organisationally part of a multi-speciality Psychology and Counselling service within a specialist Healthcare Trust itself providing services in Mental Health, Learning Disabilities and Older Adults Psychiatry. Under the umbrella of a range of service agreements and contracts Staff Support can be directly accessed by staff from our own trust, and also from Acute Hospital and Community healthcare providers and the purchasers in our ‘ District’. Additionally any Doctor or Dentist in the NHS in the Region can also access a service under a special arrangement. There are services to employees of public sector organisations locally, but the main focus here will be the application of CAT interventions and ideas for the benefit of Healthcare Staff.

Where I fit in

My role covers direct service provision to clients, developing and providing appropriate training packages, “consultant/advisor” to managers; and as speciality head I have responsibility for managing staff, for service development and evaluation, and for general guidelines and liaison about the operation of the service. As CAT has come into my thinking about my work with individuals, and indeed about myself, it has also led to a better integrated understanding about the inter- and intra-relationships within the whole service – not unlike the way specific procedures and role relationships are addressed in personal therapy in relation to target problems but gradually a whole person perspective is gained.

The work we do with the staff

We provide a range of assessment and therapeutic interventions for individuals with a “flexible guideline” of 16 sessions. Many interventions relate to:

- Screening and fitness for work

- Aftermath of work related specific trauma and distress

- Support during disciplinary or investigatory processes

- Aftermath of “institutional” problems e.g. bullying

- Work with Clients presenting depression, burnout, anxiety related to personal and work circumstances.

It is clear however that many of the specific problems for individuals exist within the context of an organisation which itself is an active partner in both the problems and the capacity to change them. Having an input via training and consultancy gives the opportunity for dialogue with parts of the organisation, which we hope in the longer term will do more towards resolving the difficulties of individual staff members.

Communicating with clients about sensitive issues

Historically in Occupational Health we have been open with our clients about sharing any letters we may write or conversations we have about them to other parties and about seeking consent for this. The NHS is both our and our client’s employer and it must be clear who the client is, at any given time. In therapeutic interventions with individual clients the prose and diagrammatic reformulations are clear and agreed representations of exactly what seems to be going on, be it about pain and the avoidance of it, about risk to the client or the patients they are caring for, or even about their capacity to be un-caring. This has proved helpful on some occasions as a basis for discussion of “third party” issues with the client and led to clearer and much more collaborative decisions about what to do about them, keeping more equality in the therapy and often moving a difficult therapy on to be more productive.

Fitness for work

In assessing fitness for work it has to be recognised that this is not an all or none state! On occasions a staff member apparently dissociates from seemingly overwhelming pain (physical or psychological), neediness and depression apparently able to continue functioning at work. Staff clients may plead not to go off sick, as the job may be the only part of their life that affords them any value, and yet concentration and judgement may be significantly impaired and when things finally fall apart they do so disastrously. Our clients may be adopting generally chaotic means of coping with neediness – such as uncontrolled eating, shopping and relationship patterns; and with overwhelming feelings by self harming, and use of alcohol and drugs. It has been helpful to use the tools and the containment of CAT to work with some clients on how they get from one state to another, describing the procedure in use and the core pain that it may be attempting to avoid.

A staff client who is self-harming will panic anyone in management who knows, since the revelation that Beverley Allit had such a history. It is important to try to see where risk to staff and patients may exist, and how to monitor the situation supportively. For example there may be a very specific pattern aimed at dealing with unbearable anger and tension which occurs when the client is alone and ruminating after feeling let down/ neglected /rejected in personal relationships. This may be based on the client’s belief that it is their fault, that they are inherently bad or valueless having been told this frequently in the past. In this respect the work by Cowmeadow (1994) has been illuminating as she talks of “establishing the nature of the emotional state associated with the self harming act” when working with self-harming patients. In the workplace the staff client may feel of value, that the work being done is good and the unbearable feelings are not present in this environment nor are triggered by it. If so there may not be any risk to patients and the client may be best staying at work.

However it may be damaging for the client if they have a tendency to allow themselves to be put upon by others in order to stay in a “valued/special” state. If the client frequently feels devalued, angry, envious of their patients’ care and needy at work then risk to patients or to themselves from the job may be present. If decisions can be made collaboratively and owned by the appropriate parties then this must auger well for the future working relationships A future possibility, provided that trust is established, may be to help the client and manager construct a diagram in order to explore the possibility of their staying at work but in a more protected environment.

The Role Relationships on offer to therapists

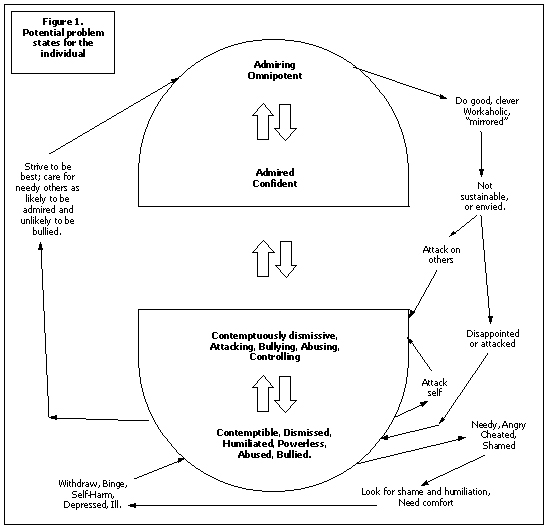

There are very strong pressures on therapists in the field of occupational health to be collusive, either with the employer, breaching confidences and seeing problem staff as unmotivated and uncaring … or there is the invitation to protect the client and sympathise with them as victim, abused, and overloaded by management. We have tended to handle this by using different staff to handle each “side”. However this keeps the “sides” split –making it difficult to see what can be owned and what is projected by each. The use of CAT tools seems to make it easier, looking at reciprocal roles to help the client see those most likely to be enacted with and by them. Many health care staff operate a split not dissimilar to that in figure 1. The need to stay in the top part – admired, special and omnipotent, well away from the perceived only alternative at the bottom – humiliated and powerless, can make it difficult for a striving, caring person to accept that in some stressful circumstances, their efforts may be damaging or alienating to patients or colleagues. This can result in the client being the subject of a complaint or worse an investigation or disciplinary action, which is utterly humiliating and will bring about collapse, cutting off and acting out; or will provoke a defensive counter attack. I have known how important it is not to collude but not always had the means to discuss what is happening with the client.

The links between personal and organisational psychology

The commonest problems we see are anxiety states and depression, sometimes a first episode, but often a reoccurrence. Whilst the main precipitant may be a recent work related problem (for example a complaint, an assault or a distressing incident) or a personal issue (quite often related to physical health, or relationship breakdown) there are generally links with much earlier pain. I had been aware of common therapeutic themes for healthcare staff from similar clinical specialities and professional groups, and whilst it is important not to generalise, CAT has assisted in thinking about these themes. Staff clients from the acute health services often describe in therapy early losses and overwhelming demands with limited chances to learn to self-care and reflect. They talk about how they coped by becoming as self-sufficient as possible, often becoming lifelong carers for others. There is often remembered shame – of poverty, neediness, feeling powerless, valueless and different from peers.

Doctors, Dentists and Senior Nurses in particular tend to describe high family expectations and levels of criticism; experience of childhood and teenage bullying is reported by many Doctors. Although it seems that having good academic skills, a good income, the power to heal, and often (but not always) very positive family encouragement and admiration would provide the escape route from powerlessness and humiliation, in fact it often doesn’t. It can lead to a blind alley of overwhelming responsibility in work and family roles – with workaholic levels of striving, fear of being exposed as a failure, and even to impatient, dismissive and bullying attitudes to colleagues and patients. The presenting problems to our service reflect this background. Perhaps not so surprising that Doctors and Dentist have such high levels of drug and alcohol abuse and high suicide rates!

Ryle (1999) discusses the split nature of borderline and narcissistic personality disorders – with the “good enough” bit in the middle being empty. He suggests that the narcissistic personality differs to borderline in that the weak and destructive aspects of the self are defended against by either grandiosity or admiration seeking from idealised others or by dismissing others as weak and contemptible. Figure 1 is based on this and has been my way of trying to think why the medical hierarchy in particular seems to permit so much bullying.

Jellema (1999) argues that it is particularly important to retain the clear procedural link to pain for narcissistic clients, who may “think but not feel” and I have found this suggestion useful with my health carer clients as a reminder that avoidance of pain is something they often excel at, particularly in therapy sessions.

An additional role pair for the acute service carers can be “abandoning to abandoned/parental child”. A commonly marked “trap” is placation to avoid confrontation and disappointing others. Self-management through self-attack and criticism is commonplace and problematic when working in hopelessly overloaded patient services.

Caring for Patients with special needs makes particular demands on the personal resources of staff possibly because of the gap between their own levels of health, ability and independence and that of their patients. This is particularly the case in providing care for people with learning disabilities, for children and for very elderly or disabled patients. However therapeutic interventions with staff clients often reveal a background of early abuse, neglect, deprivation and rejection. There may be unrealistic expectations of personal care from the workplace.

Golding (2002) reviews the problems of abuse of clients with a learning disability by paid care staff. She suggests that the type of work encourages the blurring of client/carer boundaries, because of the multiple caring, homemaking, protecting and skill development roles given often to unqualified care staff. She also notes the evidence that people with learning disabilities experience higher levels of abuse from others and may tend to “abuse provoking characteristics”. In other words there may be an “invitation” to the staff to behave abusively. This puts the onus on managers to ensure that unqualified staff in particular receive effective training, leadership, role definition, and help in managing carer/client boundaries. Kerr (1999) describes the difficulties a borderline client precipitated within a mental health team.

There appears (tentatively – this does not amount to research!) to be a slightly different emphasis in the role pairs for some of the staff from the specialist services for more psychologically or cognitively damaged clients. The “top” pair tend towards giving or getting “ideal, magical, rescuing care” with the split off lower end being about neglect, control and abuse. The low self-esteem trap features as a common procedure, many clients reporting very poor educational opportunities and fearing exposure of poor skills. A few staff clients present with clear features of borderline personality disorder and have extreme difficulties keeping patient/carer boundaries.

CAT and its relevance to Organisations

The advantages of working from within organisations are the opportunities for intervention into systems. There is a better chance of the problems and strong emotions arising in the field of healthcare being recognised, talked about and better contained within systems designed to help this- rather than a staff support service only picking up the pieces.

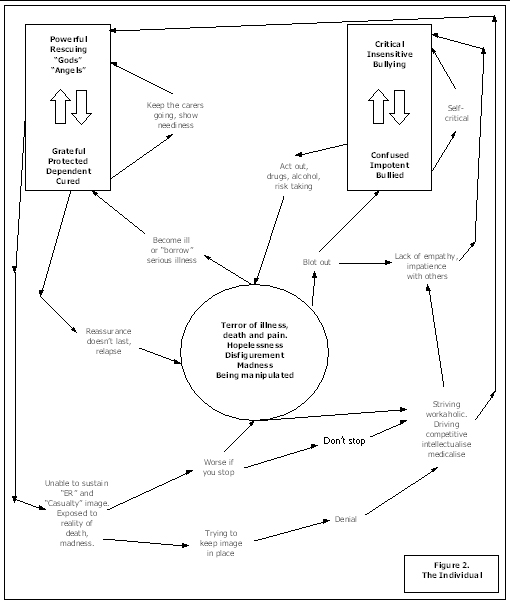

Core pain is a major concept from the early development of CAT with procedures seen as the client’s means of avoiding unbearable pain. Hale (1992) writes about the anxieties doctors experience in practising medicine. He suggests that in the general hospital setting they relate to coping with disease and death; in the psychiatric hospital coping with fears of insanity and falling apart psychologically; and in the forensic setting there is anxiety associated with patients “ who are corrupt and corrupting – of being coerced, seduced or taken for a ride”. This is shown in the centre of figure 2 along with the individual roles from figure 1 in an attempt to depict the way pain and fear might be dealt with within healthcare institutions by both staff and patients.

Main (1985) writes about projection in large groups and suggests that in an acute hospital there are only health or illness roles. Hence the staff are “healthy, knowledgeable, kind, powerful and active”; whilst the patients are “ill, suffering, ignorant, passive, obedient and grateful” He suggest that each group not only project these roles onto each other but that the projection may be “accepted” by members of the group making these individuals strive to be even more like their image.

He suggests that this temporary collusion is not problematic in, for example, a surgical ward setting, as it allows patients to get care they need, but that in longer term care settings it may lead to an unproductive split. Where there have been early life experiences of trauma in healthcare staff he believes that this will lead to the needy and uncared for parts of themselves being projected on to patients, whilst they continue as carer. If the carer breaks down eventually then the experience will be especially humiliating.

Main’s work helps in understanding what can happen in institutions if members of large groups become unable to “ reality check” whether the roles they are offering/offered actually match the skills they have. If they don’t there will be inevitable losses in job satisfaction, communication problems, blaming, paranoia, and difficulties in exercising moral responsibility and remaining logical.

Ryle (1994) proposes that projection can be seen as occurring within reciprocal roles, which, shown diagrammatically, seems to enable the explanation and prediction of projection to be done by the client as well as the therapist. In the hospital setting a staff member can be accepting the projection of the omnipotent carer role on a regular basis from many patients. If in some cases the carer is also needing to keep this role pair split from roles that connect with unbearable neediness and fear of their own, then the CAT model would suggest we look for an unhelpful procedure linking the roles and their associated feelings. When we observe bullying amongst the staff, see patients treated without empathy by impatient staff, or staff become repeatedly ill, or fearful that they are ill (figure 2) then we are probably seeing such a process.

The potential for similarity between the pain, procedural coping strategies, and roles of patients, staff, and managers and the projection of these onto each other and into the culture sometimes throws light on how the whole system is behaving.

Some research seems to support the idea of dynamic personal and systems links. Firth Cozens (1992) in her longitudinal study of junior doctors found that the main predictors of job stress were self -criticism and fathers’ age. Although there are small numbers, doctors who had suffered parental loss and separation when young were more likely to be highly stressed. She also suggests that there is preliminary evidence that poor relationships with fathers (seen as powerful, strict, intolerant and unsupportive) may predict transference onto relationships with senior doctors.

Keeping role pairs split

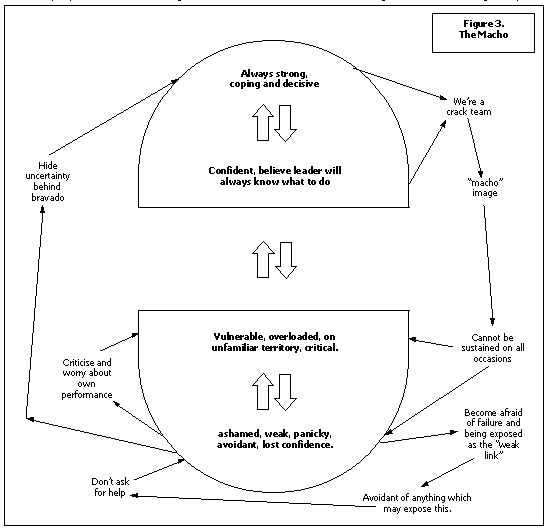

Acute Mental health and Accident and Emergency services can both require staff to react very quickly according to protocols to save life or protect safety. Some staff say that they thrive on the “adrenaline factor”! Getting caught up in a “crash” team incident or the restraint of a disturbed patient can both be frightening situations during which less experienced staff can believe their own feelings of tension detracted from their performance. Some team managers do an excellent job of normalising this, however in less sympathetic areas staff may find themselves trying to hide behind a “macho” image whilst fearing that at any time their true weakness will be exposed. (See fig 3). Things worsen as the individual becomes more senior in the team, less frequently exposed to crisis, able to dismiss their own feelings and those of their more junior colleagues. In our dialogue with the organisation for example through staff training it is vital to promote sympathetic discussion of events that may affect learning and confidence. A key element may be to look at how individuals “manage” themselves.

Walsh (1996) describes the use of CAT to look at dysfunctional relationships in a general hospital surgical theatre unit. Using evidence derived from observation and from semi structured questionnaires she produced an SDR of some common procedural loops and role relationships linking the individual staff and the organisation. This has helped me in thinking about how occupational health staff are often handed a series of “dysfunctional individuals” along with accusations and counter accusations of abuse, incompetence and poor patient care.

Walsh emphasises the importance of gathering data organisationally if it is to be used to derive an understanding of that organisation, and of being very clear about who is the client, and who has both the willingness and the position to be able to own and tackle any organisational problems.

It is unpalatable for either carers or managers to think of themselves as abusive or neglectful. Working with two individual CAT clients (highly qualified NHS Staff) who both complained of bullying and humiliation at work (as well as in their past personal lives) it became clear how they had both developed similar strategies for coping with this. The first was to strive to be perfectly caring and knowledgeable which generally brought envious counter attack and left them feeling disappointed in others who didn’t seem to try so hard. The second was to “snag” better relationships with suspicion and avoidance. Both were appalled at any suggestion that they were in any way critical of others. Looking with them at their “ self management” proved to be a first step to recognising the level of abuse and criticism to which they subjected themselves and making the connection that this was how they behaved towards others followed a bit more easily. At follow up one has reported improved relationships at work, raising some hope that work through key individuals may have some effect on the system.

When things go wrong in healthcare

The appreciation of dialogue has helped me in recognising that whole cultures are built over time in particular work areas, and are handed on to new staff. When a problem arises it is easy to look for a recent specific event or individual failure, however this can be very misleading and create a culture of blame. Investigations of clinical errors generally look at individuals not systems. This takes no account of inter or intra- personal dialogue such as “ staff who go off sick are loading their colleagues further” or “ a good surgeon is one who can work two shifts with no sleep” – which create the context in which errors generally occur.

In “problem” areas in healthcare we often see that communications have broken down, staff meetings or training events no longer happen, allegedly because there isn’t time or no one turns up. In fact it may be to avoid pain, helplessness and conflict, which could be seen procedurally as diminishing any possibility of teamwork and support, possibly promoting attack and splitting, thereby leaving even more helplessness and conflict amongst the staff.

A tragic example of there being no formal forum for discussion is quoted in the Allitt Enquiry (1991) which looked into the circumstances in which nurse Beverley Allit was able to make so many attacks on children in her care before anyone

These are probably the hardest investigated clear indications of foul play. They note that colleagues on the ward had begun to discuss informally their worries about the number of deaths on the ward but that there was no forum at which it could be raised formally. Likewise senior staff members had made individual attempts to clarify circumstances but never worked together on this.

The Harold Shipman story - Whittle & Ritchie (2000) illustrates how a person of apparently extremely grandiose and contemptuously dismissive personality, and with a background of drug abuse, was able to get into an isolated and powerful position where he could believe that he would get away with murder. Those around him appeared either to believe his grandiosity or to be suspicious but expect their ideas to be contemptuously dismissed.

At the other end of the scale there can be overuse of disciplinary procedure with staff. In our learning disabilities service the number of cases of disciplinary action against staff is far higher than in any other area, and it is linked with long periods of sickness and high referral rates to us. Some of the difficulties facing managers were noted above; they often complain that training and supervision is avoided and viewed as attacking and critical by untrained staff members. Figure 4 was produced to help ourselves think about what seemed to be presented to our service by the two “sides” and was derived from commonly described problems.

Menzies Lyth (1997) in her classic work on hospital nursing problems, notes how unrewarding the management role may be – directing insufficient resources but removed from positive feedback from the patients, possibly envying the more straightforward and protected role of the junior staff. CAT has made me think about how “Middle managers” may be feeling. They may find that their middle ground is untenable and have to choose one side of a split, identifying either with a management side or a staff/patient side. In parts of our learning disabilities service the division seems to have come in between the trained and untrained staff. Ways to improve the situation may be about more senior managers helping middle managers to occupy “good enough” middle ground and to look at alternative solutions to the disciplinary route – involving more education and support.

Where do I go next with CAT?

The experience of the course as a whole has provoked much thought about myself as an individual, a therapist, a manager, and a member of a large institution. What comes next is about matching my own zone of proximal development with those who may find the approach helpful. CAT isn’t the only therapy or the answer to all problems. – indeed it is important to remember that there are plenty of healthy procedures around that must be integrated into the picture.

CAT seems to be offering some new ways of collaborating with individual and organisational clients to develop clear, shared views of difficulties in the management of risk, pain and conflict; and to explore potential exits. It is very easy to adopt the dismissively critical position: - “fancy managing a staff member like that!” I think I am now more respectful of why problem procedures develop – that there was often no alternative, or no one to help in a dialogue about containment of difficult feelings and development of exits.

Karen Appleby

Acknowledgement

I would like to acknowledge the helpful and encouraging contribution of Val Crowley.

References

The Allit Enquiry (1991) HMSO London

Cowmeadow P. (1994) Deliberate self-harm and CAT. International Journal of Short Term Psychotherapy. 9, 2/3. 135-150

Firth-Cozens J.(1992) The role of early family experiences in the perception of organisational stress. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology. 65, 1,61-75

Hale R & Hudson L (1992) The Tavistock study of young doctors: report of the pilot phase. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 47(6) 452-464

Jellema A (1999) Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Developing its theory and practice via Attachment theory. Clinical psychology and Psychotherapy. 6, 16-28

Kerr I. (1999) CAT for borderline personality disorder in the context of a community mental health team. In CAT papers collection. Vol 2, ACAT

Main T. (1985) Some Psychodynamics of large groups. In Colman A.D. & Geller M.H. Group Relations reader 2. A.K. Rice series.

Menzies Lyth I. (1997) The functioning of social systems as a defence against anxiety. In “Containing anxiety in institutions” vol 1, Free Association Books London.

Ryle A (1994)

Projective identification: A particular form of reciprocal role procedure

. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 47, 107-114

Ryle A (1999) Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Active Participation in change. John Wiley and sons. Chichester

Whittle B. and Ritchie J. (2000) Prescription for Murder. Warner books, London

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

Appleby, K., 2003. Cognitive Analytic Therapy - its influence on my practice in the Occupational Health Speciality within a Clinical Psychology and Counselling Service. Reformulation, Spring, pp.18-24.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

CAT as a model for development of leadership skills

Mel Moss and Claire Tanner, 2013. CAT as a model for development of leadership skills. Reformulation, Winter, p.11,12,13,14.

Collaborating with Management in the NHS in difficult times

Carson, R. Bristow, J., 2015. Collaborating with Management in the NHS in difficult times. Reformulation, Summer, pp.30-36.

Thoughts on the Rebel Role: Its Application to Challenging Behaviour in Learning Disability Services

Fisher, C., Harding, C., 2009. Thoughts on the Rebel Role: Its Application to Challenging Behaviour in Learning Disability Services. Reformulation, Summer, pp.4-5.

CAT Skills Training in Mental Health Settings

Freshwater, K. and Kerr, I., 2006. CAT Skills Training in Mental Health Settings. Reformulation, Summer, pp.17-18.

Paper 1. ‘Infamy, Infamy, they’ve all got it in for me.’ 1 Exits in Organisationally Informed CAT Supervision

Sue Walsh, 2019. Paper 1. ‘Infamy, Infamy, they’ve all got it in for me.’ 1 Exits in Organisationally Informed CAT Supervision. Reformulation, Summer, pp.6-8.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

ACATnews: ACAT Virtual Office Update and ACATonline

Sloper, J., 2003. ACATnews: ACAT Virtual Office Update and ACATonline. Reformulation, Spring, p.7.

ACATnews: News from ACAT North

Bennett, D., 2003. ACATnews: News from ACAT North. Reformulation, Spring, p.7.

ACATnews: Oxford

Burns-Ludgren, E., 2003. ACATnews: Oxford. Reformulation, Spring, p.6.

ACATnews: Report from the UKCP NHS Committee

Knight, M., 2003. ACATnews: Report from the UKCP NHS Committee. Reformulation, Spring, p.6.

CAT CPD in the North of England: Some Reflections on Organising Events

Lucas, S., 2003. CAT CPD in the North of England: Some Reflections on Organising Events. Reformulation, Spring, pp.9-10.

CAT CPD Update - May 2003

Buckley, M., 2003. CAT CPD Update - May 2003. Reformulation, Spring, p.10.

Cognitive Analytic Therapy - its influence on my practice in the Occupational Health Speciality within a Clinical Psychology and Counselling Service

Appleby, K., 2003. Cognitive Analytic Therapy - its influence on my practice in the Occupational Health Speciality within a Clinical Psychology and Counselling Service. Reformulation, Spring, pp.18-24.

Developing and Promoting CAT in the NHS - Problems and Possibilities

Jellema, A., Crowley, V., Griffiths, T., Twist, G. and Gray, S., 2003. Developing and Promoting CAT in the NHS - Problems and Possibilities. Reformulation, Spring, pp.13-15.

Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought

Beard, H., 2003. Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought. Reformulation, Spring, pp.11-12.

Editorial

Nuttall, S., 2003. Editorial. Reformulation, Spring, p.3.

Evaluation of CAT in GP Practice

Baker, J., 2003. Evaluation of CAT in GP Practice. Reformulation, Spring, pp.16-17.

Initial experience of a CAT skills certificate level training for a community mental health team working with complex and ‘difficult’ mental health problems (including personality disorders).

de Normanville, J. and Kerr, I., 2003. Initial experience of a CAT skills certificate level training for a community mental health team working with complex and ‘difficult’ mental health problems (including personality disorders).. Reformulation, Spring, pp.25-27.

Letters to the Editors: Appeal for a New Treasurer for ACAT

Potter, S., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Appeal for a New Treasurer for ACAT. Reformulation, Spring, p.4.

Letters to the Editors: CAT Videos

Elia, I., 2003. Letters to the Editors: CAT Videos. Reformulation, Spring, p.4.

Letters to the Editors: Email Correction

Sutton, L., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Email Correction. Reformulation, Spring, p.4.

Letters to the Editors: Improve Your Reformulation and Contribute to Research - Try the States Description Procedure (SDP)

Ryle, T., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Improve Your Reformulation and Contribute to Research - Try the States Description Procedure (SDP). Reformulation, Spring, p.5.

Letters to the Editors: Setting up a CAT Group - Advice Welcomed

Shannon, K. and James, A., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Setting up a CAT Group - Advice Welcomed. Reformulation, Spring, p.5.

Review:

Aitken, G., 2003. Review:. Reformulation, Spring, p.30.

The ACAT Practice Research Network: What are ACAT Members' Views About What Constitutes a Minimum Dataset?

Pantke, R., 2003. The ACAT Practice Research Network: What are ACAT Members' Views About What Constitutes a Minimum Dataset?. Reformulation, Spring, p.28.

Update on the Melbourne Project

Burns-Lundgren, E., 2003. Update on the Melbourne Project. Reformulation, Spring, p.8.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.