The Impact of Different Views of God in Therapy: Healing or Perpetuating the Split in the Split Egg

Melton, J., 1995. The Impact of Different Views of God in Therapy: Healing or Perpetuating the Split in the Split Egg. Reformulation, ACAT News Spring, p.x.

THE OMNIPOTENT OTHER AND THE FALSE SELF

In the larger than life borderline scheme of things, God fits the role of the omnipotent other - either as the indulgent grandfather in the sky (complete with ruddy cheeks and long beard) in relation to the indulged darling, or else as the harsh and enraged judge in relation to the unspeakable worm. With the borderline the positive and negative attributes are similarly never held in balance, but always separated off. So that when God is experienced as wonderful. omnipotent creator with whom the admired or adored creature is in favour, the relationship is on a high and problems are excluded. When God is experienced as the punishing omnipotent destroyer, the relationship would be abandoned but for the hold that is felt over the squirming abject. victim. God is readily incorporated into the extremities of borderline constructions. In relation to divine omnipotence, the roles assumed are either sinner or saint. This supposes God to have no depth or warmth of personality. He is either for you or against you. There is no place for the biblical concept of God loving the sinner and providing a way of reconciliation.

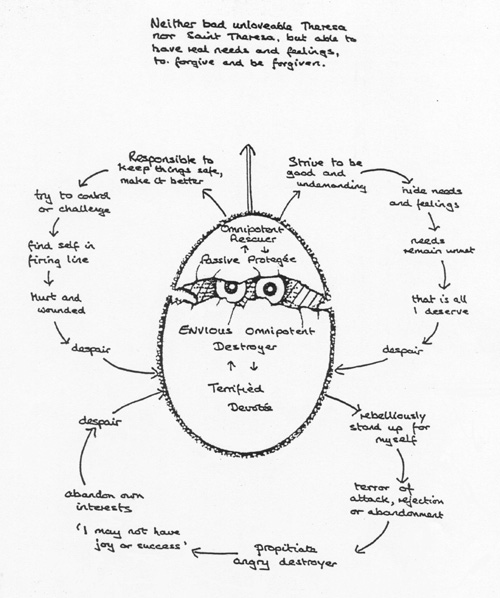

The following vignettes illustrate how God figured in the diagrams of two clients and how shifting this conception, or not, caused growth or maintained splitting. (Identifying details have been obscured.)

Theresa was a vicar's wife and the child of strictly religious parents. Her mother was experienced as cold, rejecting, critical and terrifying. (Her father was insignificant and impotent in the family.) In relation to this mother, Theresa had never been good enough, no matter how hard she tried. In reflection of the mother, God was understood emotionally as a demanding, merciless, critical judge. The fantasy that enabled her to survive but which, in constantly eluding her, brought her into despair, was that if only she could be quiescent and good enough she would be rescued from her despair and brought into symbiotic, fused bliss. Understanding how she was relating to God enabled Theresa to compare this with what she consciously believed about God, which was that, because atonement was possible, she could be just as she was before God and be loved and accepted.

Struggling with separating the myth she had been operating by from her faith, enabled her to begin to separate God from her mother, thence to separate herself out from a mother who had never allowed her acknowledgement as an individuated person with her valid needs and feelings. The shift in her relationship with God and her perceptions of herself in relation to God caused a domino effect in her other relationships and she became able to recognise herself as someone who could exist in her own right without having to be subsumed by another, and consequently she could choose to give and receive voluntarily, to respect and expect respect in return, to forgive and be forgiven. This was also worked on in the transference which provided an initial human relationship in which to try out a new scheme.

Graham was the child of critical, cold, dismissive and withholding parents, in relation to whom he was bitter, unconfident, frustrated, needy and envious. His alter persona which made life apparently bearable was as the entertainer, musician, life and soul of the party .He was acutely aware how fragile this deception was and was furious witl1 God for not magically turning the image into a reality. He could not bring himself to take responsibility for pain he caused in relationships by - his contemptuous dismissal and could only blame others in general and God in particular for his misfortune. As long as he insisted on holding God responsible for what unhappiness he experienced in relationships, he was unable to shift his procedures. He perceived God as cruelly oblivious of his pain, demanding that he should suffer, as if it would spoil God's fun to allow him to be happy. Any kind of submission to what he believed God required of him was resisted as if it would crush him totally. He could only conceive of being totally crushed or playing out an admired, successful fantasy which he couldn't believe convinced God. He was locked in position by his vying for the powerful, rejecting and contemptuous position and his inability to contemplate being vulnerable to a powerful God.

ILLUSION OR REALITY?

In the vignettes discussed above, God is cast in the role of the internalised parent, writ large, or else in a compensatory role, or both. Freud (1927) understood religion as nothing more than an illusion. Guntrip places this attitude in counterbalance to Freud's view of science as 'the fruit of man's attempt to master his universe and make himself self- sufficient', and he places the tension Freud saw between science and religion in the context of the struggle for self-sufficiency. Guntrip sees the differentiation implied by Freud's view between 'religion as infantile and science as adult' as simplistic, and suggests that dependence is, in fact an ineradicable element of human nature and the whole development of love and the affections arises out of our needs for one another' .He views religion as being 'concerned with the basic fact of personal relationship and man's quest for a radical solution to the problems that arise out of his dependent nature'.

The success or otherwise of a person's embrace of religion as 'a radical solution' perhaps depends upon whether his religion is in the fonn of a system or of a relationship, whether he is subsumed as a helpless pawn or responded to as a person making choices. I would suggest that the vignettes demonstrate that where the person feels himself to be a helpless pawn in relation to God, religion is counter-therapeutic and far from being a radical solution. In the case of the borderline split this kind of religion merely maintains the faulty conceptualisation of the world and relationships. However, where the person experiences himself to be in relationship with a loving, forgiving, fair and firm God, this can be reparative in providing better parenting than he may have had from his human parents, and can be helpful to the therapeutic process. Guntrip suggests that 'the fundamental therapeutic factor in psychotherapy is more akin to religion than to science, since it is a matter of personal relationship ...religion has always stood for the good object relationship'.

CAT theory neither denies nor asserts the existence of God but rather offers a framework of object relations in a procedural sequence model which accounts for personal variations in attitudes to and perceived relationships with God. Ry1e does not subscribe to Freud's instinct theory, but rather uses Bowlby's attachment theory as the basis of the object relations on which CAT is built. He sees attachment object relations in terms of 'inborn biological programming' of attachment behaviour which are 'designed' and 'intended' to elicit care from the mother (caretaker). He postulates sensorimotor intelligence which is involved in elaborating role procedures. There are subtle assumptions which arc not addressed. If there is programming, a programmer is suggested who can order things in accord with an intention. If there is an intention or a design, an intender or designer is suggested. It requires greater faith to believe that the sensorimotor intelligence of a newborn baby can postulate the possibility of care and devise appropriate elicitations, than it does to believe that there may be a creator God, whose intention was the surviva1 and welfare of the infant.

It then makes sense that the ultimate expression of good parenting is in the relationship of God to his creatures, which is reflected only partially in the earthly parents, since the 'image of God' in which they were created, according to Genesis, was distorted by the 'fall' from grace as man challenged God for the power to know best. The image of God in the mind of the child then becomes distorted to the degree that the parent fails to reflect the image of God in terms of love, appreciation, fairness and mercy .

Without the security which these conditions allow, it is excruciatingly difficult for the narcissist to confront his own realistic faults and limitations, also for the borderline to confront his own abusiveness. Jung comments that 'the patient does not feel himself accepted unless the very worst of him is accepted too'. This is hard for both the borderline and the narcissist to tolerate. It is far less painful in the short term to prolong and preserve the illusion of perfect care or muttJa1 admiration.

The need for the worst to be accepted is as fundamental as the need for joyful appreciation and it is necessary for these to be woven together. Unless the child gains these from the mother, it remains unable to develop an internalised self object which allows 'healthy self-assertiveness' or 'healthy admiration' without subsequent corrective experiences. The relationship with God can begin to make amends for what was missing in the empathic responsiveness of the mother. The fundamental premise of Christianity is a realistic assessment of the state of humankind - that it is in the nature of being human to have limitations, to fail in the attainment of ideals, to have needs and weaknesses which cause problems in relationship. It is precisely this failure to live up to the aspired-to image of a holy and perfect God that is met by the concept of atonement, substitution and covering through the role of Jesus. For the Christian, a denial of what would be termed sinfulness is a denial of the relevance of Jesus. So it can have a positive benefit in therapy if a person's functioning concept of God can be set alongside his belief for re-examination.

An adjusted understanding of God's unconditional love and capacity to forgive can enable a patient to accept his own painful reality and forgive himself and others.

Without the 'background of safety' that Sandier describes, or the 'environment mother' of Winnicott's, religion can render terrifying the prospect of confronting the dark areas of reality, offering only condemnation and rejection as might have been experienced from a much less than 'good enough' mother. If God is conceived of as a terrible judge waiting to pounce and punish, it is necessary to preserve the illusion of one's own and the other's goodness. for self-protection. This, I believe. is why many people have rejected what they see as the hypocrisy of the church, when they have seen legalistic religion maintaining self congratulatory smugness which overlooks the reality that is all too painfully experienced by those who are not convinced by the illusion. This is religion where the Law has been substituted for God, so that the mirror in which the person sees himself is that of unrealistic expectations.

So, if the image of God experienced from outside is harsh, legalistic, demanding and punitive, the early intemalised non-empathic, non-responsive self- object remains unmodified by the experience of religion, which reinforces the damage underlying the borderline and narcissistic disturbances. However, if the God one relates to in the outside calls out a self who can be wholly accepted, including the worst, there is bound to be a corresponding response in the background self inside, and a shift in assumptions, self-concepts, fears and ideation becomes possible. The 'false self' can be adapted.

For this reason I have begun to use the split-egg diagram as shown in the sequential diagrammatic representations accompanying the vignettes. The pictorial image suggests that the inner object relations. as described by the reciprocal roles which are written in, are actually imprinted on the personality rather than constituting the inner self. Just as the newly hatched duckling, brought up by a hen, will have a concept of itself as a chick, so the borderline brought up by an abusive parent will have a concept of himself as unlovable and have internal reciprocal roles of abusive-abused imprinted on his personality .So also the narcissist will have internal reciprocal roles of contemptuous - contemptible imprinted. The false self develops in relation to role requirements arising not from the child but from the carer. Winnicott describes how the false self emerges in adaptation to the mother who responds to her own fantasy rather than the child's need. so that the child learns to adapt to be more in tune with the mother's response than with his own inner needs.

We may conceptualise the true self as the core of one's being, whose eyes are seen in the gap of the broken egg: the primary centre or essential being of transpersonal psychology or the soul of religion. (This, I believe, goes beyond Ryle's observing eye or observing 'I', which seems to me to have more in common with transpersonal psychology's secondary centre. the personality, ','the everyday 'I'). The reciprocal roles are then not at the deepest core, but imprinted on the personality. So if the soul is accessible to a God who is warmly and deeply responsive, able to forgive the worst and delight in the response of the child/soul/person within, the false self and distorted reciprocal roles are more available for adaptation since they are not the structure of one's being, but rather the strategies of survival. These strategies are needed less if there is the security of belonging rather than being possessed, and the security of being accepted in entirety and in truth, without a false self having to intervene.

The God who is realistic about human fallibility, but merciful, is a far cry from both the harsh and punitive judge feared by both the borderline and the narcissist (and many others) and also from the benevolent Providence which is only seemingly stern' of Freud's narcissistic illusion, which is more like the idealised object favouring the special one in the fantasy side of the split egg. Where God is perceived to operate within the prescribed reciprocal roles as either abusive or in blissful fusion, or as either indulgent or contemptuous, it reinforces the borderline or narcissistic procedures. If there is a shift in the perception of God, this will encourage shifts in the procedures.

A religion that is based on the idea of being measured against a law and of having to earn conditional acceptance reiterates the experience of the abused borderline or the dismissed narcissist, that of never being good enough, never being loved I and accepted for who they are. In the Bible, Paul, in his discussion of law in Romans, says, 'Therefore no-one will be declared righteous in his sight by observing the law; rather through the law we become conscious of sin', underlining that a religion of law merely demonstrates the impossibility of the narcissistic illusion of perfection now. Instead. Paul asserts a different kind of 'righteousness' which 'comes through faith in Jesus Christ to all who believe. There is no difference no-one is better than anyone else] for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified freely by his grace through the redemption that came by Christ Jesus'. (Romans 3 v. 20-24) Jesus said, 'For I did not come to judge the world, but to save it' (John 12 v. 47), and 'I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners'. This attitude to God and to religion facilitates the borderline or the narcissist to be able to face the 'chaos and darkness' inside without such fear of condemnation or punishment, and by acceptance of his own reality and lack of perfection, to set goals, or an ego ideal, which will lead to development.

Freud saw religion as an illusion conditioned by and perpetuating neurotic infantile dependence. My own position is that God is real and a reality-based relationship with him is possible. In CAT terms, every relationship is affected by the reciprocal role procedures derived from early experience. Relationships which, by elicitation of the expected reciprocal role, confirm the early experience, tend to reinforce the faulty reciprocal role procedures which begin as strategies for surviving, making sense of and coping with less than ideal experience of childhood. Relationships, such as the CAT therapist attempts to provide, which do not conform to expectations, offer alternative experience which undermines established reciprocal role procedures and opens up the possibility of adapted and more effectively functioning role procedures.

The cognitive technique used in CAT, of testing out the reality of assumptions can be used in checking out whether the image of the God one relates to, in terms of expectations of his response, is consistent with the image of God held in conscious belief and origins of understanding. The same process of checking out, as is used in other relationships, can operate to challenge counterproductive assumptions which maintain reciprocal role procedures split between an idealised fantasy and a polarised painful replaying of damaging early experience.

Correction of faulty assumptions and development of reality- based procedures is nurtured in relationships that begin to shift towards realistic expectations and aspirations and acceptance of 'good enough' responses. The degree of change effected by the different experience of relationship within and outside of therapy depends on the significance of the relationship to the patient. If the relationship with God has significance, the effect of a shift towards a more accurate perception of God's responses can be profound, particularly because that relationship is all pervasive. In just the same way, the persistence of faulty perceptions that reflect the damaging early experience can sabotage the effectiveness of therapy if this relationship remains unattended to. For that reason, for the person who has any concept of God, it is important that his place on the SDR and the significance of the relationship with him is acknowledged.

The impact of the relationship with God can best be explained by Anna (in Mister God this is Anna): "But Mister God is different. You see. Fynn, people can only love outside and only kiss outside, but Mister God can love you right inside, and Mister God can kiss you right inside, so it's different. Mister God ain't like us, we are a little bit like Mister God, but not much yet. ...Mister God can know things and people from the inside too. We only know them from the outside, don't we? So you see, Fynn, people can't talk about Mister God from the outside; you can only talk about Mister God from the inside of him."

This paper was delivered at the 3rd ACAT Conference February 1995

References

The Bible, New International Version, Hodder and Stoughton

Bowlby, J. 1969. Attachment and Loss. Vol 1: Attachment. New York. Basic Books.

Frank. J. 1961. Persuasion and Healing, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press.

Freud, S., 1927. The Future of an illusion, Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, Hogarth Press

Fynn, 1977. Mister God this is Anna. Collins, Fount Paperbacks.

Guntrip, H., 1961. Personality Structure and Human Interaction, Hogarth Press.

Jung. C.G., 1933. Modem Man in Search of a Soul, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Mahler, M. 1968. On Human Symbiosis and the Vicissitudes of Individuation. N. Y., International University Press.

Mollon, P. 1993. The Fragile Self, Whurr Publishers

Ryle. A. 1985.

Cognitive Theory, Object Relations and the Self

, Br Journal of Medical Psychology 581-7.

Ryle. A. 1990.

Cognitive Analytic Therapy - Active Participation in Change: New Integration in Brief Psychotherapy

, Wiley Series in Psychotherapy and Counselling.

Ryle. A. 1991.

Object Relations Theory and Activity Theory: A proposed link by way of the Procedural Sequence Model

, Br. Journal Med. Psychology. 64 307-316.

Ryle, A. The Concept of Projective Identification - a clarification.

Sand1er, J. 1960. The background of safety, Intemationa1 Journal of Psychoanalysis 41 352-356.

Winnicott, D. 1965. The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment, New York. International University Press

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

Melton, J., 1995. The Impact of Different Views of God in Therapy: Healing or Perpetuating the Split in the Split Egg. Reformulation, ACAT News Spring, p.x.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Narcissism: From Kohut to CAT

Pollard, C., 1997. Narcissism: From Kohut to CAT. Reformulation, ACAT News Winter, p.x.

Nacissism - A CAT Perspective

Tanner, C. and Webster, P., 2003. Nacissism - A CAT Perspective. Reformulation, Summer, pp.16-18.

Reflections on a Dilemma in a Supervision group: Caught between a Rock and a Hard Place

Gil-Rios, Dr. C., M., and Blunden, Dr. J., 2012. Reflections on a Dilemma in a Supervision group: Caught between a Rock and a Hard Place. Reformulation, Summer, pp.23-25.

Family Constellations and CAT: Reciprocal Roles Through The Generations?

Bancheva, M., 2006. Family Constellations and CAT: Reciprocal Roles Through The Generations?. Reformulation, Summer, pp.15-17.

Some Subjective Ideas on the Nature of Object

Dunn, M., 1993. Some Subjective Ideas on the Nature of Object. Reformulation, ACAT News Autumn, p.2.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

A Study of Birth Stories and Their Relevance for CAT

Wilton, A., 1995. A Study of Birth Stories and Their Relevance for CAT. Reformulation, ACAT News Spring, p.x.

The Impact of Different Views of God in Therapy: Healing or Perpetuating the Split in the Split Egg

Melton, J., 1995. The Impact of Different Views of God in Therapy: Healing or Perpetuating the Split in the Split Egg. Reformulation, ACAT News Spring, p.x.

The Therapeutic Relationship and Therapy Outcome

Gopfert, M. and Barnes, B., 1995. The Therapeutic Relationship and Therapy Outcome. Reformulation, ACAT News Spring, p.x.

The Use of Transference in CAT: Refinement of a Proposed Model

Bennett, D., 1995. The Use of Transference in CAT: Refinement of a Proposed Model. Reformulation, ACAT News Spring, p.x.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.