A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities

Wells, S., 2009. A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.21-23.

Introduction

There is increasing research on the use of CAT with clients with learning disabilities (LD) (Collins, 2006; David, 2009; Moss, 2007; Psaila & Crowley, 2006). Studies have shown that with modifications, reformulations which describe complex psychosocial concepts and processes, can be conveyed in a way suitable for this population (e.g. King, 2006). There remains a dearth of research however, looking at the impact of CAT on these clients from their own perspectives. This is especially so, given the importance of service user experiences in evaluating service delivery and the explicitly collaborative nature of CAT. A study was therefore conducted to evaluate CAT from the perspective of five clients with LD. The participants for this study were recruited from a Community Learning Disability Team in the West Midlands.

The key questions for this study were:

- How did the client come to receive therapy?

- What do clients with learning disabilities recall of their experience of receiving CAT?

- What are client’s general feelings about receiving therapy?

- Have things changed since clients received therapy?

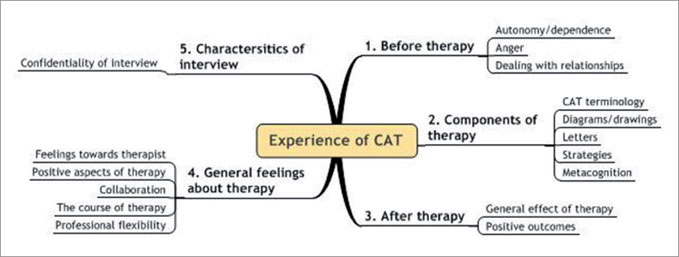

A semi-structured interview schedule was developed around these open-ended questions, supplemented by prompts (Lofland & Lofland, 1995). The five resultant transcripts were subjected to a theoretically-based thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) which resulted in 167 initial codes. Following inter-rater coding and refinement, the collation of codes resulted in five main themes and sixteen sub-themes (figure 1):

The main findings of this study will be discussed in accordance with these five main themes:

Before Therapy

All of the clients were able to talk about what life was like for them before attending therapy and were able to identify the main problems with which they presented. These ranged from low or changeable mood, anxiety, relationships with others, offending behaviour and aggression. One of the main sub-themes to emerge was anger, experienced to a problematic degree by a majority of the participants. It is interesting to note that the clients who identified anger as a specific issue were less likely to be able to identify their emotional state prior to therapy. These clients were also less likely to identify specific thought patterns, but instead described sequences of behaviour in more concrete terms. With regards to the efficacy of CAT in helping clients to deal with issues related to anger, for all of the clients who identified anger as a target problem, associated behaviours had reduced following completion of therapy.

The other major theme that all of the participants identified as a problem was dealing with relationships. In a large-scale meta-analysis, Kavale and Forness (1996) found that around 75% of clients with learning disabilities displayed social skills deficits and that the majority experienced significant difficulties in dealing with relationships. In the present study, although there was no formal record taken of social skills, anecdotal evidence would suggest that relationship difficulties did not increase with the degree of learning disability, perhaps only providing further evidence for one of the central tenets of CAT: that patterns of relationship are at the root of [all] human distress (Ryle and Kerr, 2002).

Components of Therapy

Most of the participants in this study used terminology specific to CAT. This is in itself a positive outcome, given that one of the stated aims of CAT is to make the language of therapy more understandable for clients (Llewelyn, 2003). Perhaps more importantly however, was that a majority of clients spoke about working on their difficulties in a way that it implied the incorporation of CAT reformulation methods (e.g. RRPs). On the limited basis of this study, this internalisation did not appear to be related to participants’ diagnoses, but did appear to be directly related to participants’ ability to recollect the diagrams produced in therapy and participants’ tendency to use metacognition in their account. It is perhaps the nature of pictures that complex information can be described in an eloquent and memorable form (Ryle & Kerr, 2002) and evidence from this study suggests that diagrammatic formulations were substantially more memorable than when in letter form. In fact only a minority of participants remembered using or receiving letters during therapy. This does not in itself suggest that reformulation letters had no effect, but that they were not explicitly incorporated as were diagrammatic reformulations. In addition, although no formal measures of participants’ prior tendency to use metacognitive appraisals was made; the widespread use of these during interviews could also be an outcome of therapy. The fact that most of these statements were not made explicitly, would suggest that participants were not simply recalling information in response to direct questions, but that specific components of CAT had been internalised and were being utilised independently.

After Therapy

The results of this study would indicate that all of the participants were independently using techniques or ‘strategies’ directly related to their experience of CAT. One participant, whose relationship to his therapist mirrored previous close relationships in which he felt dependent, made explicit statements regarding ‘pushing for independence’ in applying the coping strategies he had learned. Similar statements by other participants suggested that not only were the core components of CAT internalised, but so was a sense of autonomy in applying them to one’s life independently. These two elements may well explain the positive outcomes for all five of the participants in this study. Not only could participants give examples of how their lives had changed in concrete observable terms, but they could all relate this directly to changes within themselves. For one client in particular, the reduction in self-injurious and previously incapacitating obsessive-compulsive behaviours had enabled him to travel independently to a nearby city and marked a radical change in his life. This was all the more significant given the social presentation of this client (Aspergers Syndrome) and the repeated bullying that he had received from local youth.

General Feelings About Therapy

In general, the participants in this study were very positive regarding their experience of therapy. One of the most important aspects of therapy for several of the clients was to be able to speak to someone in confidentiality. Given that dependency is a frequently occurring issue for people with learning disabilities (Hollins & Sinason, 2000; Morrison & Cosden, 1997) it is perhaps not surprising that clients often wanted to talk about their relationships with their family or staff members. The participants from this study came into contact with a large range of services and with many of these, they did not feel that the information they relayed was confidential. Having a professional who was primarily concerned with supporting the client was therefore felt to be a very significant relationship.

The results of this study would also suggest that most of the participants felt that CAT was a collaborative experience. The type of questions used in the interviews clarified that for these participants they felt listened to and that reformulations were arrived at with equal input from client and therapist.

Conclusions

This study adds to the growing literature which shows that CAT can be effectively used with clients with learning disabilities, and produces valuable outcomes for clients. This is despite continued pessimism regarding the efficacy of psychotherapy with this population (Hollins & Sinason, 2000; Wilner, 2005).

This study also provides preliminary evidence that learning-disabled clients who receive CAT view this form of therapy positively, feel that they are engaged in a collaborative process and incorporate the core components of CAT into their own conceptualisation of their problems. This conceptualisation and the resultant strategies gained are applied independently by clients after therapy has finished.

The results of this study appear to indicate that the internalisation of CAT is most effectively achieved through the use of diagrams and not by letters. This conclusion is based however upon the explicit recall of participants and therefore the more implicit effect of letters could thus be under-represented. Further research could clarify the relative effectiveness of the reformulation methods (e.g. letters and diagrams etc) and their relationship to metacognition and internalisation in people with learning disabilities.

Finally, there still exists a relative paucity of research into the experiences of people with learning disabilities from their own perspectives. As Gerber and Reiff (1991) point out, ethnographic research is invaluable in hearing the voices of this marginalised population. This study has sought to add to this under-represented and much needed area of research.

I would like to thank Dr Nichola Murphy and the clinicians and participants who kindly agreed to help me with this study. Thank you.

References

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

Collins, S. (2006). “Don’t dis me!” using CAT with young people who have physical and learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter (2006), 13-18.

David, C. (2009). CAT and people with learning disability: Using CAT with a 17 year old girl with disability. Reformulation, Spring (2009), 8-14

Gerber, P. J. & Reiff, H. B. (1991). Speaking for Themselves: Ethnographic Interviews with Adults with Learning Disabilities. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Hollins, S. & Sinason, V. (2000). Psychotherapy, learning disabilities and trauma: new perspectives. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 32-36.

Kavale, K. A. & Forness, S. R. (1996). Social skill deficits and learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29 (3), 226-237.

King, R. (2000). CAT and learning disability. Association of Cognitive Analytic Therapy News, Spring (2000), 3-4.

Llewelyn, S. (2003). Cognitive analytic therapy: time and process. Psychodynamic Practice, 9 (4), 501-520.

Lofland, J. & Lofland, L. H. (1995). Analysing Social Settings (3rd Edition). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Morrison, G. M. & Cosden, M. A. (1997). Risk, resilience and adjustment of individuals with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 20 (1), 43-60.

Moss, A. (2007). The application of CAT to working with people with learning disabilities. Reformulation, Summer (2007), 20-27.

Psaila, C. L. & Crowley, V. (2006). Cognitive Analytic Therapy in people with learning disabilities: An investigation into the common reciprocal roles found within this client group. Mental Health and Learning Disabilities: Research and Practice, 2 (2), 96-108.

Ryle, A. & Kerr, I, B. (2002). Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Principles and Practice. Chichester: Wiley.

Wilner, P. (2005). The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for people with learning disabilities: A critical overview. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. Special Issue: Mental Health and Intellectual Disability: XVI, 49 (1), 73-85.

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

Wells, S., 2009. A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.21-23.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Cognitive Analytic Therapy in People with Learning Disabilities: an Investigation into the Common Reciprocal Roles Found Within this Client Group

Psaila, C.L. and Crowley, V., 2006. Cognitive Analytic Therapy in People with Learning Disabilities: an Investigation into the Common Reciprocal Roles Found Within this Client Group. Reformulation, Winter, pp.5-11.

Relational patterns amongst staff in an NHS Community Team

Staunton, G. Lloyd, J. Potter, S., 2015. Relational patterns amongst staff in an NHS Community Team. Reformulation, Summer, pp.38-44.

Capturing Service Users’ Views of Their Experiences of Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT): A Pilot Evaluation of a Questionnaire

Phyllis Annesley and Alex Barrow, 2018. Capturing Service Users’ Views of Their Experiences of Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT): A Pilot Evaluation of a Questionnaire. Reformulation, Winter, pp.14-21.

Exploring whether the 6 Part Story Method is a valuable tool to identify victims of bullying in people with Down’s Syndrome

Pettit, A., 2012. Exploring whether the 6 Part Story Method is a valuable tool to identify victims of bullying in people with Down’s Syndrome. Reformulation, Winter, pp.28-34.

Editorial

Lloyd, J., and Pollard, R., 2014. Editorial. Reformulation, Summer, pp.3-4.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

A Brief Survey of Perceptions of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Within Local Mental Health Systems

Turley, A., Faulkner, J., Tunbridge, V., Regan, C. and Knight, E., 2009. A Brief Survey of Perceptions of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Within Local Mental Health Systems. Reformulation, Winter, p.26.

A Call For Papers On The 3rd International ACAT Conference

Elia, I., 2009. A Call For Papers On The 3rd International ACAT Conference. Reformulation, Winter, p.25.

A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities

Wells, S., 2009. A Qualitative Study of Cognitive Analytic Therapy as Experienced by Clients with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.21-23.

Chair’s Letter, October 2009

Westacott, M., 2009. Chair’s Letter, October 2009. Reformulation, Winter, p.3.

Cognitive Analytic Therapy, or Can You Make a Mad Man Sane?

Anonymous, 2009. Cognitive Analytic Therapy, or Can You Make a Mad Man Sane?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.11-13.

Darwin and Psychotherapy

Elia, I., 2009. Darwin and Psychotherapy. Reformulation, Winter, p.9.

Dialogue and Desire: Michael Bakhtin and the Linguistic Turn in Psychotherapy by Rachel Pollard

Hepple, J., 2009. Dialogue and Desire: Michael Bakhtin and the Linguistic Turn in Psychotherapy by Rachel Pollard. Reformulation, Winter, pp.10-11.

International ACAT Conference “What Constitutes a CAT Group Experience?â€

Anderson, N., M., 2009. International ACAT Conference “What Constitutes a CAT Group Experience?â€. Reformulation, Winter, pp.25-26.

IRRAPT 2007-9 Research Projects

McNeill, R., 2009. IRRAPT 2007-9 Research Projects. Reformulation, Winter, p.26.

K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple. Stupid) - Reflections on Using CAT with Adolescents and a Couple of Case Examples

Jenaway, A., 2009. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple. Stupid) - Reflections on Using CAT with Adolescents and a Couple of Case Examples. Reformulation, Winter, pp.13-16.

Letter from the Editors

Elia, I., Jenaway, A., 2009. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Winter, p.3.

Letter to the Editors

Anonymous, 2009. Letter to the Editors. Reformulation, Winter, p.6.

Measurements of change and their relationship to each other in the course of a CAT therapy

Gallagher, G., Inge, T., McNeill, R., Pretorius, W., O’ Rourke, D. and Wrench, M., 2009. Measurements of change and their relationship to each other in the course of a CAT therapy. Reformulation, Winter, pp.27-28.

Recieving a CAT Reformulation Letter: What Makes a Good Experience?

Newell, A., Garrihy, A., Morgan, K., Raymond, C., and Gamble, H., 2009. Recieving a CAT Reformulation Letter: What Makes a Good Experience?. Reformulation, Winter, p.29.

Research Into the Use of CAT Rating Sheets

Coombes, J., Taylor, K. and Tristram, E., 2009. Research Into the Use of CAT Rating Sheets. Reformulation, Winter, pp.28-29.

The Big Debate - Health Professions Council

Jenaway, A., 2009. The Big Debate - Health Professions Council. Reformulation, Winter, p.7.

Threats to Clinical Psychology from the CBT Stranglehold

Lloyd, J., 2009. Threats to Clinical Psychology from the CBT Stranglehold. Reformulation, Winter, pp.8-9.

Using what we know: Cognitive Analytic Therapy's Contribution to Risk Assessment and Management

Shannon, K., 2009. Using what we know: Cognitive Analytic Therapy's Contribution to Risk Assessment and Management. Reformulation, Winter, pp.16-21.

When Happy is not the Only Feeling: Implications for Accessing Psychological Therapy

Lloyd, J., 2009. When Happy is not the Only Feeling: Implications for Accessing Psychological Therapy. Reformulation, Winter, pp.24-25.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.