CAT and People with Learning Disability: Using CAT with a 17 Year Old Girl with Learning Disability

David, C., 2009. CAT and People with Learning Disability: Using CAT with a 17 Year Old Girl with Learning Disability. Reformulation, Summer, pp.21-25.

Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) is a brief, time-limited therapy designed to address the needs of the large numbers of people presenting to NHS Services with psychological distress (Llewelyn, 2003, Ryle & Kerr, 2002). Over time it has been applied to an increasing range of problems, such as severe and enduring mental illness (e.g. Kerr, Crowley & Beard, 2006) personality disorder, anorexia nervosa, and organisational/staff group difficulties (Llewelyn, 2003). Whilst there is little research into use of CAT with clients with learning disability, anecdotal reports from clinicians and single case studies indicate that with some adaptations (e.g. symbolised SDR), CAT can be effective with this client group also (Clayton, 2001; Lloyd, 2007; King, 2000, Psaila & Crowley, 2006).

This case study, my first using CAT, describes work with a client in an inpatient setting for people with learning disabilities. It was completed as part of a CAT Skills course run within my employing Trust. All identifying information has been removed or changed to maintain the client’s anonymity.

Referral Information

Amy was referred for therapy by her nurse. She was described as displaying a pattern of challenging and self-injurious behaviour. She had previously attended 20 CAT therapy sessions with a different clinician. It was reported that these had been helpful. Following an initial assessment and discussion within my supervision group, it was felt appropriate to offer 16 sessions, rather than the 24 suggested by Ryle (2004), as Amy was already familiar with this way of working.

Background information

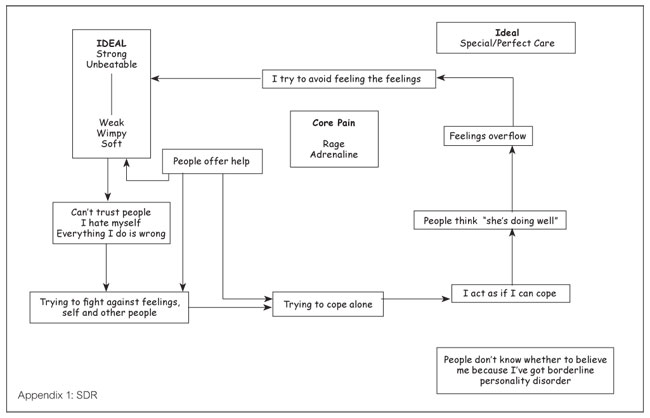

Amy was 17 years old, with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and borderline learning disability. Amy did not see herself as having a learning disability or mental health problems, but described herself as ‘troubled’ and ‘disturbed’ with anger and behaviour problems.

Amy’s parents separated when she was a child. Her mother was the victim of domestic violence, and Amy often witnessed this. She felt guilty about being unable to stop it.

She recalled her parents being very critical and leaving her ‘to her own devices’ as she was growing up. She felt betrayed, let down, and uncared for by them. In contrast Amy had a very close relationship with her granddad who had passed away when she was still a child, leaving her feeling very alone.

She described having been bullied for most of her life, but as a teenager she began to fight back. She spoke of wanting respect and believed fighting was the only way to achieve that.

Amy had made numerous attempts to take her own life and had been admitted to hospital for mental health reasons on various occasions. During her most recent admission, she had continued to self-injure and damage property when distressed and was often physically restrained by staff to prevent further injury to herself and other people.

Pre-therapy

An initial 4 assessment sessions were arranged to discuss what CAT would involve and gather background information. I was advised in supervision that CAT therapy proper could begin when I was certain the client was giving informed consent and was able to provide a narrative. In hindsight, this was apparent within the first session. I believe it was my own anxiety, stemming from my inexperience with the CAT model that led me to suggest these initial sessions. I was unsure how Amy’s learning disability would impact on her ability to engage in therapy and of my ability to identify whether the CAT model would be suitable for her, despite her having worked in this way before.

Reformulation

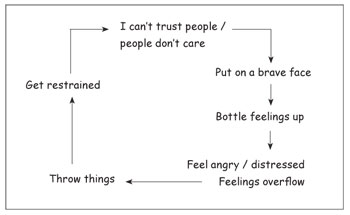

During the pre-therapy sessions, it became apparent that Amy was seeking perfect/special care (her ideal) (e.g. when staff were not immediately available to her, she felt that they did not care). However, her past experiences led her to believe that she was not deserving of care and that those who offered care would betray her. Consequently, she kept her feelings ‘bottled up’. This was not sustainable and inevitably the feelings overflowed. This trap (figure 1 – identified during pre-therapy sessions) gave us two clear, but inextricably linked, target problems that we agreed to focus on: ‘Not trusting people to share thoughts and feelings’ and ‘bottling feelings up until they overflow’.

Figure 1: Trap

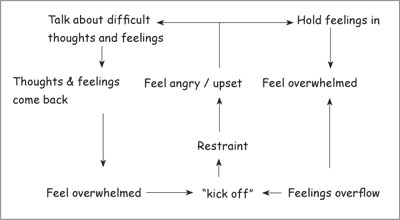

Using Amy’s description of what happened between sessions, her brief reports of her early experiences, and our relationship within the session, a dilemma (figure 2) and a reciprocal role of ‘strong/unbeatable to weak/wimpy/soft’ (Amy’s words) were quickly identified. These indicated very black and white thinking on Amy’s part. She believed that she could either hold everything in and be strong or show emotion, but either way she would end up feeling overwhelmed and weak.

Figure 2: Dilemma

Whilst the psychotherapy file was offered to Amy on a number of occasions, she chose only to complete the different states questionnaire. Her responses centred on feelings of agitation, confusion, rejection, abandonment, humiliation, and cutting off from feelings. All of which were reflected in her target problem procedures.

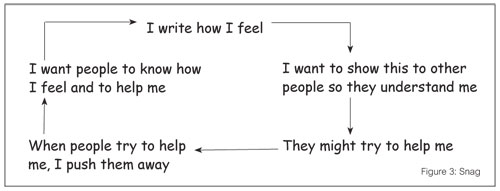

I worried that without completing the psychotherapy file, we would struggle to develop an SDR. Furthermore, Amy had clearly said she wanted support, but when I offered the psychotherapy file as part of this process, she dismissed it. This pattern emerged on a number of occasions throughout therapy and characterised a snag (Figure 3) that sabotaged attempts to support Amy. On reflection, I do not believe anything was lost by Amy not having completed the psychotherapy file, but it did help to identify the ‘dismissing—dismissed’ RR.

I was aware that developing the SDR should be a collaborative venture. However, Amy did not seem to value it. She was reluctant to look at it, often preferring to turn her back on me when I brought it out. On one occasion, she snatched it from me and said she ‘hated it’. However, towards the end of our work together, she described the ‘patterns and circles’ as being the most useful aspects of our work together. It seemed that the diagram triggered painful feelings for her (perhaps vulnerability and shame, although she did not state this); Amy worried she might lose control if she focused on her feelings. However, it also felt containing in its ability to predict what might happen in situations.

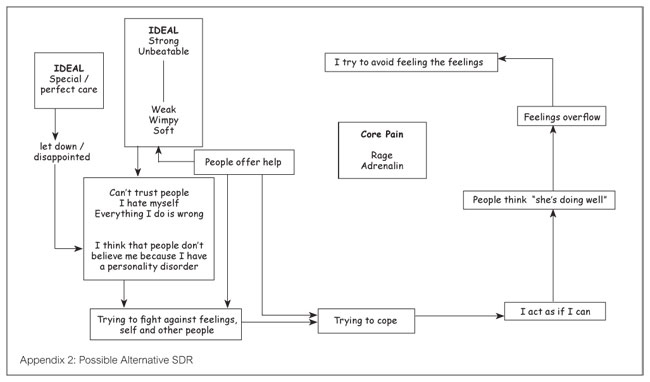

On the SDR (Appendix 1), Amy’s idealised situation was placed outside the trap that she found herself stuck in. This made sense to Amy and seemed to illustrate that it felt out of reach. On reflection, it might have been appropriate to put the idealised position, or situation, alongside the reciprocal role, with a second ideal being the strong/unbeatable position. This possible alternative SDR is illustrated in appendix 2.

When I shared my reformulation letter with Amy (session 7), she chose to read it herself. She masked her feelings about the letter with nervous giggles and refused to discuss them with me. She was concerned that discussing the letter would trigger strong feelings that would overwhelm her and push her into the ‘wimpy’ position and that I would be unable to cope. I secretly worried how I would cope if she became overwhelmed, but I was also aware that she had few other opportunities to express her emotions in a containing environment. I reflected on a previous session when she had been upset, but we had coped together. She was adamant that this was different and changed the subject. This was a clear example of her ‘bottling feelings up’ trap; Amy described it as ‘blocking out’.

Over time it became clear that ‘blocking out’ occurred when Amy had something to look forward to (e.g. a visit home) or was working towards (e.g. tribunal). She worried that if she expressed her feelings, they would overwhelm her and she would jeopardise the event. I believe this recognition indicated progress in Amy’s journey towards managing her emotions in a more helpful way. She was beginning to verbalise the thoughts behind the ‘blocking out’, which helped carers support her more effectively.

Recognition and Revision

Session 7 felt like a turning point. Amy had been reluctant to discuss whether she recognised her trap, dilemma, or snag occurring. I struggled to see how we could begin to revise these patterns without Amy recognising and reporting them. Having shared my reformulation letter, I was persistent in my attempts to persuade Amy to reflect on the points in her diagram where I believed she was stuck (pushing help away, bottling feelings up). Amy responded by beginning to write about her life on the computer during our sessions. She felt that I had not been listening to her and that other people did not listen. She believed that by writing, people would hear her story.

Amy’s previous accounts of her early experiences had been told in a way that felt rehearsed and without much expression of feeling. What followed felt much more personal. I would read the story as she typed and shared my reflections about what she had written. At times, this led to discussion about her experiences. On other occasions, she simply continued to write and did not respond to my comments. It was unclear why on one occasion she would discuss what she had written and on another she chose not to

Amy used writing on the computer to talk about her difficult past and how this left her feeling. She remained composed whilst doing this and seemed to find this a more comfortable way of sharing her thoughts and feelings. She also did not appear to ‘block things out’ as much as she had done in previous sessions. Over time she moved from talking about her earlier experiences to her current thoughts and feelings. Towards the end of our work together, she began to share some of what she had written with the care staff to help them understand what she was feeling.

Exits were not addressed formally in sessions as this seemed to be outside of Amy’s zone of proximal development. Time was therefore used to work towards recognition. However, on one occasion, Amy described being able to talk herself down from feeling angry during a disagreement with a member of staff. This was an important step forward for Amy who at other times had hit out or hurt herself in similar situations.

Rating sheets were introduced in session 9 and we agreed Amy would try to record, between sessions, examples of the trap we had identified earlier in our work together. However, she chose only to complete one rating during our work together and had no interest in the forms. I was frustrated that she again seemed to be pushing away the help that was offered, and I got a sense of what it might be like to be in the weak/wimp position of her RRP.

Termination and Follow up

From the very first session we discussed that therapy would be time-limited. After our pre-therapy sessions we agreed on 16 sessions and, as is common practice with my learning disability clients, Amy was given a written timetable so she could tick these off as she attended them. From session 12, I reminded Amy that our sessions were coming to an end and encouraged her to reflect on what this meant for her. She described feeling that she had been left to fight a war on her own by other professionals who had moved jobs. My suggestion that she also felt I was leaving her alone to fight was affirmed.

Gradually, over the final four sessions Amy began to ‘block off’ from her feelings and talked about situations at a more superficial level or avoided topics of conversation altogether. Furthermore, from session 13 she sought to finish the sessions early. When I challenged her on these points she acknowledged that she was weaning herself off the sessions and was protecting herself against feelings of being left alone. Previously she would have become irritated by these challenges. She was clearly at the point of trying to cope alone, and in characteristic fashion she chose not to look at the diagram when I suggested this to her.

I shared my ending letter in session 16. In this I reflected on my frustration when the help I offered was pushed away. However, I also acknowledged the brave step Amy took in sharing aspects of her life with me on the computer and how this strategy had allowed her to retain control of her feelings. I was aware that Amy might feel let down if she felt that all her goals had not been achieved. I therefore included reflections on what had been achieved and how she could carry this on once therapy ended. As with the reformulation letter, Amy chose to read it herself and again made no comment about it. She described feeling ‘not bothered’ that our sessions were ending and I was left feeling dismissed. She seemed to be striving for the ‘strong/unbeatable’ position. I wonder if this protected her against the vulnerability of feeling abandoned. Although invited, Amy chose not to write a goodbye letter.

I was sad that our sessions had ended, but was aware of the importance of maintaining boundaries and consistency when many other areas of Amy’s life felt unsafe or uncontained. I was tempted to continue with sessions, but felt that this sudden change of rules would add to her confusion and insecurity. My supervision group provided invaluable support and guidance in making and keeping to this decision.

With Amy’s permission I shared her SDR with her named nurse. It was evident that staff on the unit felt pushed into ‘weak/wimpy/soft’ position and they struggled to know how to help Amy when she appeared to ‘throw it back at them’ by harming herself or damaging property. The SDR helped the staff to understand Amy’s position. Nevertheless, they felt that the unit was not a suitable environment for Amy and shortly after our sessions ended she was moved to another unit. I reflected with staff on how this could leave Amy feeling rejected and confirm her belief that no one could cope with her, but also that it may impact on her ability to develop trust with the new staff team. Discussions with staff on the new unit indicated that Amy settled in very quickly. Whilst there were some episodes of self-harm, staff felt able to support her at these times.

At the review session some two months later Amy reported feeling more settled and pleased with the increased independence that she was beginning to have on the new unit. However, she also found this difficult to adapt to and felt that staff were less available to her, which she perceived as their abandoning her. She refused to look at her diagram and seemed to be in the position of trying to cope alone. However, the member of staff who accompanied her reported that there were some anxieties that she was now willing to discuss and only occasionally became unsettled (e.g. upset, self-harming) to the point where she required physical intervention or medication to help her calm down. As no new problems had emerged it was agreed that Amy would be discharged.

Reflections on the Process of Therapy

Although Amy had a learning disability, I did not need to adapt the tools of therapy to any significant extent. She was able to read and had a good level of understanding of the written word. To have used symbols on the SDR would have felt insulting as she clearly understood what was illustrated, although at times she chose not to use it.

When discussing difficult issues, Amy would often giggle in a childlike way but could also become quite dismissive of the therapy and its tools. This was reminiscent of Ryle’s (2004) observation that when individuals with borderline personality disorder are faced with unmanageable emotions, or the prospect thereof, they dissociate or switch between states. As a result, I was left feeling powerless and annoyed that she would not accept the help I was offering. I also felt very deskilled at a time when I was already anxious about learning how to apply a new therapeutic model. Over time I became more able to recognise that Amy was replaying patterns illustrated on her SDR, which in turn enabled me to recognise that her behaviour did not necessarily indicate a deficit in my therapeutic skills.

Conclusions

CAT was new to me. Although I read about the model and its tools I sometimes struggled to translate this into practice. For example, to start with, I found it quite difficult to identify TPPs from what Amy said. Discussion and guidance within my supervision group was invaluable in helping me to develop these skills. In addition, I was used to working cognitively and the group helped me to think more analytically and to use the relationship with Amy as a therapeutic tool.

I now feel more confident in my ability to use a CAT informed approach with other clients. I found the idea of TPPs particularly helpful and these ideas have already begun to inform my other work.

Claire David, Clinical Psychologist, Brooklands, Birmingham

would like to acknowledge the support and guidance of her supervisor, Val Crowley, as well as the support provided by her supervision group whilst working on this case.

References

Clayton, P. (2001). Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy in an institution to understand and help both client and staff. G. Landsberg & A. Smiley (Eds). In Forensic Mental Health: working with offenders with mental illness. New Jersey: Civic Research Institute.

Kerr, I.B., Crowley, V. & Beard, H., (2006). A cognitive analytic therapy-based approach to psychotic disorder. In J.O. Johannessen, B.V. Martindale & J. Cullberg (eds). Evolving psychosis: different stages, different treatments. East Sussex: Routledge.

King, R. (2000). Cognitive analytic therapy and learning disability. ACAT news.

Llewelyn, S (2003). Cognitive analytic therapy: time and process: Psychodynamic Practice, 9, 501-520.

Lloyd, J. (2007). Case Study on Z: Not as impossible as we had thought. Reformulation, Summer, 2007, 31-39

Psaila, C.L & Crowley, V. (2006). Cognitive Analytic Therapy in people with learning disabilities: an investigation into the common reciprocal roles found within this client group. Reformulation, Winter 2006, 5-11

Ryle, A. (2004). The contribution of cognitive analytic therapy to the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(1), 3-35.

Ryle, A. & Kerr, I.B. (2002). Introducing cognitive analytic therapy: principles and practice. Chichester: Wiley.

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

David, C., 2009. CAT and People with Learning Disability: Using CAT with a 17 Year Old Girl with Learning Disability. Reformulation, Summer, pp.21-25.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually

Murphy, N., 2008. CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually. Reformulation, Summer, pp.26-30.

CAT and Learning Disability

King, R., 2000. CAT and Learning Disability. Reformulation, ACAT News Spring, p.x.

Creatively Adapting CAT: Two Case Studies from a Community Learning Disability Team

Smith, H., Wills, S., 2010. Creatively Adapting CAT: Two Case Studies from a Community Learning Disability Team. Reformulation, Winter, pp.35-40.

Tyler's Story. Cognitive Analytic Informed Therapy within a Secure Care Setting

Dr Kim Liddiard, 2020. Tyler's Story. Cognitive Analytic Informed Therapy within a Secure Care Setting. Reformulation, Summer, pp.31-34.

Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities

Frain, H., 2011. Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

A Little Italian Story – Service Development

Fiorani, C., Poggioli, M., 2009. A Little Italian Story – Service Development. Reformulation, Summer, pp.13-14.

Aims and Exits from Self-Defeating Procedures

Toye, J., 2009. Aims and Exits from Self-Defeating Procedures. Reformulation, Summer, pp.26-29.

Book Review of: Beatrice Beebe and Frank Lachmann (2002). Infant Research and Adult Treatment: Co-constructing Interactions. Published London: Analytic Press.

Lloyd, J., 2009. Book Review of: Beatrice Beebe and Frank Lachmann (2002). Infant Research and Adult Treatment: Co-constructing Interactions. Published London: Analytic Press.. Reformulation, Summer, pp.34-35.

Book Review of: How Infants Know Minds. Reddy, V. (2008). Harvard University Press.

Ryle, T., 2009. Book Review of: How Infants Know Minds. Reddy, V. (2008). Harvard University Press.. Reformulation, Summer, pp.33-34.

CAT and People with Learning Disability: Using CAT with a 17 Year Old Girl with Learning Disability

David, C., 2009. CAT and People with Learning Disability: Using CAT with a 17 Year Old Girl with Learning Disability. Reformulation, Summer, pp.21-25.

CAT Effectiveness: A Summary

Quraishi, M., 2009. CAT Effectiveness: A Summary. Reformulation, Summer, pp.36-38.

Letter from the Editors

Elia, I., Jenaway, A., 2009. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Summer, p.3.

Meeting with Older People as CAT Practitioners: Attending to Neglect

Sutton, L., Gaskell, A., 2009. Meeting with Older People as CAT Practitioners: Attending to Neglect. Reformulation, Summer, pp.6-13.

Obtaining Consent to Publish – Further Thoughts

Toye, J., Lloyd, J., Jenaway, A., 2009. Obtaining Consent to Publish – Further Thoughts. Reformulation, Summer, p.3.

Reflections on Our Experience of Running a Brief 10-Week Cognitive Analytic Therapy Group

John, Dr C., Darongkamas, J., 2009. Reflections on Our Experience of Running a Brief 10-Week Cognitive Analytic Therapy Group. Reformulation, Summer, pp.15-19.

State Regulation of Psychotherapy: Protecting the Public or ‘Professionalising’ Psychotherapy at the Expense of Therapeutic Integrity, Creativity and Diversity?

Pollard, R., 2009. State Regulation of Psychotherapy: Protecting the Public or ‘Professionalising’ Psychotherapy at the Expense of Therapeutic Integrity, Creativity and Diversity?. Reformulation, Summer, pp.29-31.

The CAT Articles Review

Knight, A., 2009. The CAT Articles Review. Reformulation, Summer, p.32.

Thoughts on the Rebel Role: Its Application to Challenging Behaviour in Learning Disability Services

Fisher, C., Harding, C., 2009. Thoughts on the Rebel Role: Its Application to Challenging Behaviour in Learning Disability Services. Reformulation, Summer, pp.4-5.

Update on Statutory Regulation

Westacott, M., 2009. Update on Statutory Regulation. Reformulation, Summer, p.20.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.