Reformulating the NHS reforms

Jones, A. and Childs, D., 2007. Reformulating the NHS reforms. Reformulation, Summer, pp.7-10.

Dear Staff,

You have come for help because you feel a lack of enthusiasm for your work. You’ve told me that you find the new proposals for Foundation Trust status result in feelings of apathy, disinterest, and despair or that they are clinically irrelevant. Although you used to care about how best to organise a service fair, accessible to everyone and free; now you feel you cannot rouse the interest or motivation to bother about yet another change.

You have told me how, in the past, your work used to inspire you. You had a lot more freedom in those days, to work as you felt was helpful, to take work in new and innovative directions, to feel valued, in return for what you had to offer. You and your colleagues had time for training and supervision, and you never reckoned the hours of overtime you put in, and weren’t being paid for. Giving felt good and being supported, you wanted to give.

It’s hard to say exactly when things first started to change for the worse, especially as many of the organisational changes seemed to have a positive slant to them too, like being clearer about defining services, or making sure people with the greatest need had their fair share of time. So it was hard to notice at first the shift that was happening. But gradually, over the last decade, you have noticed the whole quality change, as if the heart has gone out of the work you do. You now feel that you are no longer trusted simply to get on with your job, but need to be checked and controlled like an errant child. There has been more and more concern about money. It’s been harder for managers to run the service within budget, and there have been cuts in services that seem not to fit an overall plan, or make much sense. This creates uncertainty and an apparently irrational working environment that must be faced every day. You can’t see things getting better, and feel that they are likely to get worse, because the criteria for Foundation Trusts are largely commercial. Already, you have told me that your Trust has put an embargo on externally funded supervision, and that you can no longer obtain funding for training that you need, or time off to go to it. You worry a lot about the future of your own service and your own job.

In the light of the above we have agreed the target problem to be;

I don’t know how to understand or put right my relationship with the NHS A number of procedures relate to this;

The ‘It’s pointless so why bother?’ Trap Believing that I am a useless pawn, or that the NHS reforms are driven by a logic unrelated to clinical reality, I feel it’s pointless for me to try and make any difference to plans. Consultation feels like an empty exercise, so I don’t take part, go to meetings or try to have a voice. This means I’m even more outside of changes when they happen, increasing my belief that I really am ineffective, and my sense of worthlessness.

Uneasy conformist or marginalised rebel Dilemma Either I try to express and protect the values I believe in but sound archaic and get ignored Or I go through the motions, do the minimum possible but feel uncomfortable and alienated in my role at work.

Striving to meet demands Feeling uncertain about my value in the organisation, I attempt to meet demands put on me. But the more I try, the more demands are made, and eventually I feel overwhelmed and exhausted. I become demoralised and this increases my sense of worthlessness

As you are hearing this you may feel like withdrawing and not getting involved in any exploration of this kind, perceiving it to be pointless. You might feel it’s better to get on with the way you have been coping already, but feel that something vital has been left out. Alternatively, you might feel that by getting involved in exploring this, others will see you as ‘not on board’ with the way that changes are happening. I hope we can find a way of working with these painful issues in the weeks ahead.

Comment This letter is an attempt to explore some of the issues arising from the introduction of Foundation Trusts in the NHS. This move will, in effect, mean that each Trust will be expected to ‘modernise’ by becoming a business in its own right, competing for patients with other Trusts instead of working together to provide a National Service. Patients will be encouraged to ‘choose’ which hospital they consider best, and money will ‘follow the patient’.

We see a number of difficulties with this model, as well as the effect on staff we have described above.

Firstly, Trust income will reflect individual treatment episodes but few existing contracts are written in this way.

Moreover mental health work is generally hard to lump into units of standard cost.

Secondly, people want to choose their treatment or their clinician rather than decide between health providers. For complex problems, choice of a distant health provider would raise questions of travel, liaison and contact with family and carers. If we, for a moment, consider the financial and time costs of extra contractual placements under the present system, we can see the reasons for keeping such treatment exceptional.

Thirdly, there is little scope for a market: “independent providers…generally only provide certain specialist services for which there are no market alternatives” (Dept of Health 2006). Secondary mental health services have been restricting work to the severely mentally ill, already excluding the very people and the types of work which best suit a health market.

Because of this we are concerned that there may be a perverse incentive for Foundation Trusts to develop the types of services that attract discreet patient monies, to the detriment of other mental health services. This may result in the wealth of one Trust being enhanced, and others, who fail to keep afloat financially, being reduced to ‘core services’.

The new local membership of Foundation Trusts will have very little effective influence and the requirements of financial survival will move from being a heavy constraint on core clinical purposes to becoming the ultimate organisational logic. New Foundation Trusts may indeed find that they have a relative advantage in relation to other members of what was known as the local health community, but over time we believe the advantage will be trivial by comparison with what is sacrificed.

Strikingly the immediate effect on the organisation working toward this extra ‘freedom’ is an imposed conformity. The criteria for qualification are primarily to do with being able to trade; (the ability to price, financially balance, and manage accounting for professional practice). So the organisation has to be reviewed and changes made for business rather than clinical reasons. For example, the aim of competing by cost of episode may require a shift to management by care group rather than by locality, straining partnerships with social care.

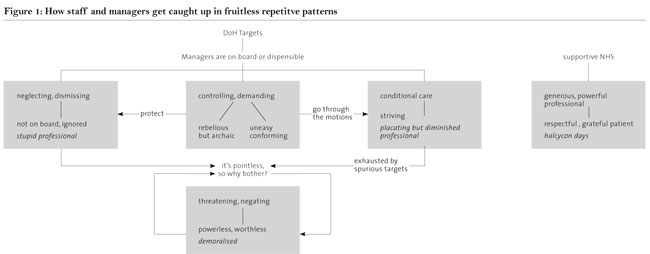

Because such changes are not clinically justifiable, there is a tendency toward pseudo-consultation with staff. In our diagram (Fig 1), we have attempted to show how managers are often under considerable pressure to implement directives from above.

They may feel that if they are not ‘on board’ with changes, they can be replaced by someone who is. This can result in controlling and demanding behaviour and communication with clinicians through hasty and sham consultation processes implemented in often clumsy and insensitive ways. We have described how clinicians can either attempt to buckle under and conform to demands (Placating but diminished professional), or, try to protect the values they believe to be important, ending up ignored and seen as archaic (‘stupid’ professional). Both these states lead into a position where management becomes increasingly threatening and negating of professionals, resulting in feelings of powerlessness and worthlessness in the professionals. The placating professional becomes burdened by spurious targets, sheer volume of work, and an overwhelming sense of futility; the ‘stupid’ professional experiences a sense of exclusion from the organisation. We have represented earlier experiences of working in the NHS as a split off, idealised state in which patients were grateful and respectful to the generous and powerful professional (Halcyon Days).

In terms of CAT theory, what we observe is a tightening of magistral scaffolding for forward thinking and change within the organisation, albeit one presenting itself through an apparent dialogue and in the interest of a future carnival of local opportunity. This is of course not true.

We hope that by understanding these pressures, staff would be better placed to support managers to question the very changes they are attempting anxiously to impose.

What can a few psychotherapists do about all this? We would suggest that we can demonstrate and insist on dialogue. We consider that an exit has to be discovered through a working expression of dialogue.

We use the word dialogue in two senses. First, it describes an active linking with other groups and colleagues from other Trusts in order to give more weight to the emergent opinions or advice. Secondly, it is a new way of relating to managers, involving them in a more ‘Socratic’ interchange. We know that managers in applicant Trusts are in the position of having to prove their Trusts fit for foundation status rather than being able to negotiate sensible conditions for change. This makes it hard for them to talk about the dangers and disadvantages of the application for foundation status. These can be raised in the consultation process by other staff (and stakeholders) who may be able to bring up points that are obvious but unmentionable by those most closely involved. Comment from staff which could, for example, include a reformulation for managers alongside organisational proposals, may allow them to recognise their own position and consider a different sort of dialogue as a choice after all.

As the application process tends to isolate Trusts from the local health community and from other specialist providers, groups of applicant Trusts may eventually, through these processes of dialogue, be able to raise common concerns. These may perhaps first have been articulated through contacts between their respective professionals and may result in applicant Trusts being in a stronger position to alter the local and national planning ‘scaffolding’.

CAT Council can be asked to make it clear that there must be no restriction on free circulation of any knowledge that may improve services or clinical practice. Also, CPD standards for training and supervision for CAT and other therapists are a condition for safe practice not a soft saving. Currently we know that it is the practice in some Trusts to make this ‘saving’ already, by putting an embargo on training and externally funded supervision.

It is worth remembering that the government put Local Authorities in a position of choosing between three ways of no longer being responsible for their housing stock. In response a number have identified a ‘fourth way’, keeping the option for public housing (Centre for Public Services 2004). There is silence on what happens if NHS Trusts do not accept the government’s invitation to bend themselves toward becoming Foundation Trusts. We need a respectable option as Health Trusts in order to remain part of a local health and social care public service community with a first duty to provide equitable health care. Let’s put our theory into practice within our Trusts and begin the dialogue!

Alysun Jones is a CAT psychotherapist working part time in the NHS in Bristol.

David Childs is a clinical psychologist. We gratefully acknowledge help and advice with this article from Barbara Williams.

References

Centre for Public Services (2004) The case for the fourth option for council housing. Sheffield. CPS. available at www.european-services-strategy.org.uk

Dept. of Health (2006) Applying for NHS Foundation Trust Status. A Guide for Mental Health NHS Trusts. London. available at www.dh.gov.uk

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

Jones, A. and Childs, D., 2007. Reformulating the NHS reforms. Reformulation, Summer, pp.7-10.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Anonymous Letters

Anonymous, 2012. Anonymous Letters. Reformulation, Winter, pp.22-23.

Letters to the Editors: Association of Adult Psychotherapists (AAP)

Webster, M., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Association of Adult Psychotherapists (AAP). Reformulation, Autumn, pp.3-4.

CAT in the NHS: Changes as a result of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the future of CAT

Vesey, R., 2012. CAT in the NHS: Changes as a result of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the future of CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

Letters to the Editors: Agenda for Change and Psychotherapy

Nield, C., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Agenda for Change and Psychotherapy. Reformulation, Autumn, p.3.

Editorial

Lloyd, J. and Pollard, R., 2012. Editorial. Reformulation, Winter, pp.3-4.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

Book Review: Just War. Psychology and Terrorism

Collins, S., 2007. Book Review: Just War. Psychology and Terrorism. Reformulation, Summer, pp.18-19.

Case Study on Z not as Impossible as we had Thought

Lloyd, J., 2007. Case Study on Z not as Impossible as we had Thought. Reformulation, Summer, pp.31-39.

Generating Practice-Based Evidence for CAT

Marriott, M. and Kellett, S., 2007. Generating Practice-Based Evidence for CAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.40-42.

Keeping cat alive

Ryle, A., 2007. Keeping cat alive. Reformulation, Summer, pp.4-5.

Reformulating the NHS reforms

Jones, A. and Childs, D., 2007. Reformulating the NHS reforms. Reformulation, Summer, pp.7-10.

The Application of CAT to Working with People with Learning Disabilities

Moss, A., 2007. The Application of CAT to Working with People with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-27.

The Inner Voice Check

Elia, I., 2007. The Inner Voice Check. Reformulation, Summer, pp.28-29.

Using CAT in an assertive outreach team: a reflection on current issues

Falchi, V., 2007. Using CAT in an assertive outreach team: a reflection on current issues. Reformulation, Summer, pp.11-17.

You’re driving me insane: Literature, Lyrics and Drama through CAT eyes for clients and students

Elia, I. and Jenaway, A., 2007. You’re driving me insane: Literature, Lyrics and Drama through CAT eyes for clients and students. Reformulation, Summer, pp.43-44.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.