Using a template to draw diagrams in Cognitive Analytic Therapy

Jenaway, Dr. A. and Rattigan, N., 2011. Using a template to draw diagrams in Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Reformulation, Summer, pp.46-48.

Introduction

Given that many of the training cases now taken on in mental health services are actually quite difficult patients, often with a diagnosis of personality disorder, we have found ourselves using a template for CAT diagrams to help trainees in their initial attempts to develop simple, working diagrams. Several people have requested that we write something about it for Reformulation. In his article in the last issue of Reformulation, Steve Potter (2010) describes how to start “mapping while talking” early on with the client and to work collaboratively towards a usable diagram. However, this can be hard for trainees who are fairly new to CAT and who are feeling anxious to get it right. We have found that, paradoxically, having a template in mind can help trainees to relax and be more collaborative when faced with a blank sheet of paper and a patient who finds it difficult to understand, or even describe themselves. It means that you have some idea of where to put the reciprocal roles or states of mind, that the client is describing, making it less likely that you both end up with an incomprehensible muddle. We have also used it, on occasion, with clients who are struggling to understand the point of a diagram, or why we keep sketching things. Teaching the client the template, drawing it out as a general description of how people develop their procedures, and then encouraging them to think about how their own issues, roles and behaviour would fit on to the template can be very helpful (see case example below). The template we have developed was first suggested by Michael Knight (personal communication) and so we are reluctant to claim credit for it. However, Michael has been reluctant to write about it so here goes……

A Developmental Model of Reciprocal Roles, leading to a template

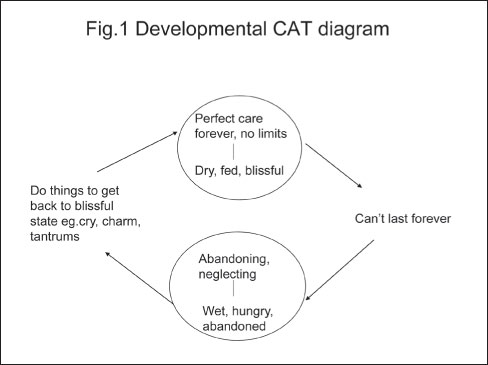

We all start life completely dependent on those caring for us, we are vulnerable and powerless and must start to make sense of the world and try to find ways of getting our needs met. We can think about this beginning as two extreme states, either I am warm, fed and loved, feeling blissful, all desires met, or things are not quite right and I am wet, cold, hungry, feeling abandoned and alone. In these extreme states, our carer is either totally caring and in tune or abandoning and rejecting. In the ideal world, the baby is only made to wait for tiny amounts of time until it’s needs are met again and the blissful state is reached once more, but no parent is totally in tune. Quickly, the baby starts to develop ways of getting their needs met, or at least signalling that they are not being met. Thus, on the left hand side are the procedures which the healthy baby develops to try and get it’s needs met – crying, smiling, temper tantrums etc. On the right hand side are the things which go wrong or interrupt the state of bliss and send the baby back down to the unwanted state at the bottom of the diagram. A.J. has used this developmental model with parents to try and explain personality development in their struggling child or adolescent (2009). (Fig 1)

The Adult Version

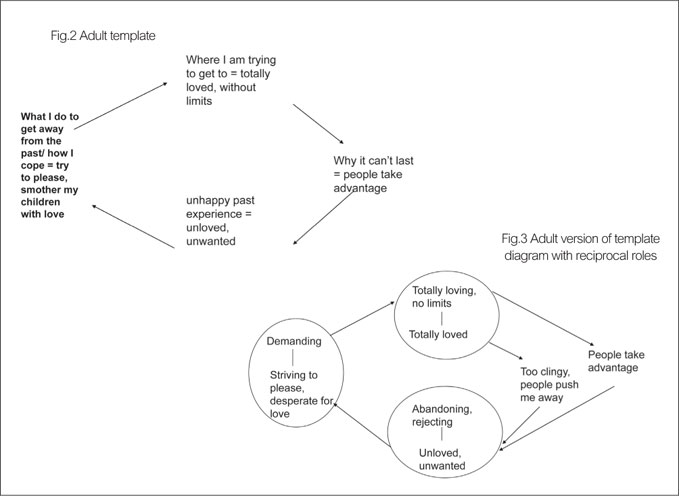

The explanation when working with an adult may be similar to the developmental one, explaining that we all start as a tiny baby trying to work out how to get our needs met in the environment we find ourselves in. Most adults are able to describe what was difficult for them in their childhood, either in terms of a feeling state, such as constantly feeling “unwanted” or “unloved”, or in relational terms, such as “my mother never wanted me, she rejected me from the start”. These difficult states or relationships are put at the bottom of the diagram as the difficult place, or state which I try to get away from (see fig 2). They can be written initially as feeling states and the reciprocal roles added later if this is appropriate (see fig 3). On the left hand side are “the things I do to try and get away from that horrible place/relationship role. Again this might be a procedure, such as placation or “trying too hard to please”, or it could be written as reciprocal roles. At the top of the diagram is the state or relationship that the client is constantly striving for, for example “totally loved” or “constant approval”, this is usually the opposite extreme to the feared state. It is quite straightforward at this stage to point to the empty middle of the page and say something like “It’s not surprising that you were so overprotective with your own children as you had never experienced the “middle ground” of good enough care. The final place on the right of the template is the reason why things go wrong and the longed for state cannot last, such as “people take advantage” or “I get too clingy and people push me away”, thus leading to the person crashing back down to the feared state yet again.

Clients seem to find it very easy to see the circular nature of their problems when drawn out in this way and very quickly start saying things like “but I don’t know how to be in the middle”, or start using the diagram to make sense of other issues not yet talked about.

Case Example

John was a 54 year old, single gentleman. He was retired, lived alone and spent all his time caring for his elderly and demanding parents. He described a 25 year history of recurrent depression. He had been admitted to psychiatric hospitals on three occasions in the previous 15 years and had also undergone several alcohol detoxes. He had attempted to take his own life in 2000 when he lost his job, his house and a long-standing relationship. He had been prescribed a wide range of psychotropic medications and a course of ECT, none of which had been particularly effective.

Prior to his referral for C.A.T. he had engaged well with professionals and valued Art Therapy which he had found challenging but had made him look at himself and think about what had gone wrong.

At the start of therapy, John described himself as having nothing in his life apart from his dog of whom he was extremely fond; he was suffering from chronic low mood and felt that he had “lost his nerve” around people. He was socially isolated and felt that his life was totally boring. He had been abstinent from alcohol for 10 years; looking back he thought he had used alcohol to boost his confidence and to manage low mood. He described having been a “rising star” early in his career in management but he had been “a total perfectionist” and had driven himself too hard. He had always felt out of his depth and that he could never achieve what was expected of him.

John likened his childhood to an emotional desert; neither of his parents ever showed him affection and only “A1” achievement could ever gain him praise. His exuberant and exploratory temperament regularly brought him into conflict with his parents who valued the quiet studiousness of his elder brother. He learnt to give in for a quiet life. Family lore had it that he had nearly killed his mother who had experienced complications during his birth and he thus grew up under a cloud of blame.

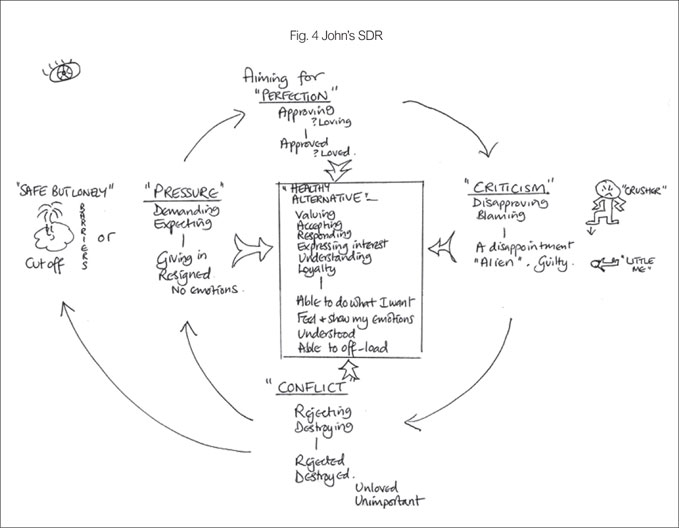

It was only when he got to University that John enjoyed a social life for the first time but though socially skilled in making conversation (and later in dealing with people at work), he remained mystified and scared by expressions of affection, sadness or vulnerability. He had lived his life as though he must either stay disconnected (safe but lonely) or else he would have to give in to other people’s demands, striving for their approval but inevitably experiencing criticism and ultimately rejection. In therapy, we identified a harshly critical, inner voice that John named “Crusher”.

The Mother – Infant template and explanation of how reciprocal roles develop was introduced in session 2. John readily understood the concept and appeared to find this way of thinking about himself helpful. We were able to immediately locate key problematic roles to the four positions on the diagram. The aim of achieving perfection had been expressed at our first meeting when John was talking about his job but, as we talked about his experience of being parented, John was able to link this to longing for affection (or even acceptance) from a very early age. It proved invaluable to John to see that the pressure to get things right and the sense of never being good enough had started in his childhood, as had his aim of avoiding conflict by giving in. Later additions to the basic 4 positions were the safe but lonely “island” and the cartoon drawings of “Crusher” and “Little me”. The limited description of healthier, less extreme reciprocal roles that would characterize “good enough” relationships is unusual and reflects the difficulty John had in identifying and articulating these due to a lifetime of social isolation (his first attempts were drawn from his relationship with his dog). Although the healthy alternative reciprocal role position is drawn in the middle of this diagram, in therapy we constantly talked about the need to be able to move, flexibly between reciprocal roles. By the end of therapy John had determined to become a better parent to his inner child but there was insufficient room on the diagram to add all of these roles.

Conclusion

We would like to thank, Michael Knight for inspiring us to think about using a template to explain the development of reciprocal roles to our clients. It is a simple but powerful teaching aid which introduces the client to the CAT model and can lead seamlessly into the construction of a diagram. In so doing, we have discovered that an additional benefit of the template is that it empowers trainee CAT therapists who are often scared of “drawing” in general or CAT diagrams in particular. Feedback from our trainees suggests that they hold the 4 positions in mind and that this is a useful tool in getting started, even if they end up jointly creating a unique and more creative version of an SDR with their client.

References

Potter, S. (2010) “Words with arrows. The Benefits of Mapping Whilst Talking.” Reformulation, issue 34, p37 – 45.

Jenaway, A. (2009) “Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy with parents: some theory and a case report.” Reformulation, issue 29, p12 - 15

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

Jenaway, Dr. A. and Rattigan, N., 2011. Using a template to draw diagrams in Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Reformulation, Summer, pp.46-48.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Change your Parenting for the Better - exploring CAT as a parenting intervention

Dr Alison Jenaway, 2013. Change your Parenting for the Better - exploring CAT as a parenting intervention. Reformulation, Winter, p.32,33,34,35,36.

Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy with parents: some theory and a case report

Jenaway, A., 2007. Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy with parents: some theory and a case report. Reformulation, Winter, pp.12-15.

Split-Egg Fantasies: Incorporating Fantasy into a Developmental Model of CAT

Dr Lawrence Howells, 2019. Split-Egg Fantasies: Incorporating Fantasy into a Developmental Model of CAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.36-40.

An Alternative Psychotherapy File

Alison Jenaway, 2017. An Alternative Psychotherapy File. Reformulation, Winter, p.48.

K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple. Stupid) - Reflections on Using CAT with Adolescents and a Couple of Case Examples

Jenaway, A., 2009. K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple. Stupid) - Reflections on Using CAT with Adolescents and a Couple of Case Examples. Reformulation, Winter, pp.13-16.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

Aim and Scope of Reformulation

Hepple, J., Lloyd, J., Shea, C., 2011. Aim and Scope of Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, p.56.

An audit of Goodbye Letters written by clients in Cognitive Analytic Therapy

McCombie, C., Petit, A., 2011. An audit of Goodbye Letters written by clients in Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Reformulation, Summer, pp.42-45.

Book Review: Lacanian Psychoanalysis, Revolutions in Subjectivity

Pollard, R., 2011. Book Review: Lacanian Psychoanalysis, Revolutions in Subjectivity. Reformulation, Summer, pp.23-28.

Book Review: The Mindfulness Manifesto

Wilde McCormick, E., 2011. Book Review: The Mindfulness Manifesto. Reformulation, Summer, p.28.

CAT, Metaphor and Pictures: An exploration of the views of CAT therapists into the use of metaphor and pictorial metaphor

Turner, J., 2011. CAT, Metaphor and Pictures: An exploration of the views of CAT therapists into the use of metaphor and pictorial metaphor. Reformulation, Summer, pp.37-41.

Dear Reformulation

Hughes, R., 2011. Dear Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, p.22.

Flowers by the Window: Imagining Moments in a Culturally and Politically Reflective CAT

Brown, R., 2011. Flowers by the Window: Imagining Moments in a Culturally and Politically Reflective CAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.6-8.

Is CAT in danger of being squeezed out of the NHS?

Waft, Y., 2011. Is CAT in danger of being squeezed out of the NHS?. Reformulation, Summer, pp.18-21.

Is three a crowd or not? Working with Interpreters in CAT

Emilion, J., 2011. Is three a crowd or not? Working with Interpreters in CAT. Reformulation, Summer, p.9.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Hepple, J., 2011. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.4-5.

Letter from the Editors

Hepple, J., Lloyd, J. and Shea, C., 2011. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Summer, p.3.

Memoirs, Myths and Movies: Using Books & Film in Cognitive Analytic Therapy

Jefferis, S., 2011. Memoirs, Myths and Movies: Using Books & Film in Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Reformulation, Summer, pp.29-33.

Six-Part Storymaking – a tool for CAT practitioners

Dent-Brown, K., 2011. Six-Part Storymaking – a tool for CAT practitioners. Reformulation, Summer, pp.34-36.

The Effectiveness of Standard Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) with people with mild and moderate acquired brain injury (ABI): an outcome evaluation.

Rice-Varian, C., 2011. The Effectiveness of Standard Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) with people with mild and moderate acquired brain injury (ABI): an outcome evaluation.. Reformulation, Summer, pp.49-54.

The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview

Hepple, J., 2011. The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview. Reformulation, Summer, p.55.

Using a template to draw diagrams in Cognitive Analytic Therapy

Jenaway, Dr. A. and Rattigan, N., 2011. Using a template to draw diagrams in Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Reformulation, Summer, pp.46-48.

What are the most dominant Reciprocal Roles in our society?

Ahmadi, J., 2011. What are the most dominant Reciprocal Roles in our society?. Reformulation, Summer, pp.13-17.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.