Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes. Reformulation, Winter, pp.53-55.

Introduction

Over the last three years I have been working in the liaison psychiatry team at Addenbrooke’s hospital in Cambridge. The team takes referrals from the general hospital of a wide range of patients who are presenting with physical illness and trauma. There was already an experienced Cognitive Behaviour Therapist on the team, and so we have had to think about which patients might be better suited to a CAT approach. This has often been determined by patient preference but I have tended to see those whom the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist felt would be less suitable for CBT. This includes those patients who have a past history of relationship difficulties, severe childhood abuse or trauma, or a history of behaviours that indicate some kind of personality difficulty, such as self harm. One group that I have become particularly interested in working with are patients who present to the general hospital with physical symptoms that cannot be explained, and do not seem to fit with any known medical condition. This has included patients with non-epileptic seizures (fits which look a bit like epilepsy but do not show up on the electrical tests on the brain which demonstrate epilepsy), and other neurological disorders such as paralysis, loss of voice, tremors, and spasms. Some other specialities also refer patients, particularly the gastroenterology team (problems with the gut, such as persistent unexplained vomiting) and other doctors who are known to be good at diagnosing rare or complicated disorders and so are the last port of call if no diagnosis has been found yet! These patients often seem to be out of touch with their feelings and find it difficult to make any link between their symptoms and stress so it is quite difficult to use a standard CBT approach. CAT can also be useful as a way of offering contextual reformulation to medical teams, where the patient is not interested in engaging in therapy.

Medically unexplained symptoms

Around 25% of consultations in a GP practice are for symptoms that turn out to have no significant physical explanation, and this is even higher in hospital outpatient clinics. The term has become a bit trendy recently and is now being used to cover a very wide range of disorders, from syndromes that are thought to have a significant psychological component such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, to disorders of somatisation. Some of these appear more like old fashioned conversion disorder, where psychological conflicts are expressed through the body, and in some patients, there may be a suspicion that they are causing their own illness, for example by taking non-prescribed medication or by infecting wounds. Some of these patients attend very frequently and through their distress, or through direct demands, push doctors into doing more and more tests, some quite invasive. The tests can cause anxiety and have side effects themselves, thus generating even more symptoms. Some patients, who are convinced they are seriously ill, give up certain activities and become more and more dependent on their family or friends, leading to even more problems and further distress and anxiety. The recommended approach from doctors, when they see this pattern emerging, is to limit tests and referrals, offering a psychological explanation, and referral for psychotherapy in mild to moderate cases (Gill & Bass, 1997). A CAT contextual reformulation can help doctors to see the relationship roles that they are being pulled into – perhaps rescuer to rescued? This can make it easier to stand back and set limits around referrals or investigations.

It is important not to take a stance of no further investigations ever though, as often symptoms are only currently medically unexplained and occasionally further tests, or a new doctor, does come up with a physical diagnosis. Also, I believe that psychotherapy, in helping resolve some of the psychological distress, or the minimisation or exaggeration of symptoms, can help doctors see more clearly what the problem really is and make a better physical diagnosis.

What can CAT offer?

This depends a bit on how patients are thinking about their symptoms when they are referred, some have accepted the idea that the illness has something to do with their experience of childhood abuse, for example, even though they cannot see any connection themselves. Others come with an open mind, thinking that there may be some connection and not particularly wedded to the idea of a physical cause for the symptoms. A third group seem to come only to keep the physicians happy and are pretty convinced that the illness is physical despite what they have been told. This third group are difficult to engage and the prognosis for change is poorer. The advantage of the CAT model, and it’s complexity, is that I can honestly say that I am not too bothered about whether the illness is a genuine physical one or a psychosomatic one as your relationship with yourself, your symptoms, your body and the clinicians looking after you, are just as important whatever the cause of your illness. To me, all illnesses are both physical and psychological. Even if you have a broken leg, the way you react to it, whether you are able to rest and recover, how you respond once the plaster is taken off, are all dependant on your relationship patterns. We know from Jackie Fosbury’s research in diabetes that CAT can be very helpful for patients struggling with serious illness (Fosbury et al, 1997). I will explain a bit more about what I am listening out for in the next section, but what I am offering the patient is a chance to explore what their early relationships were like and how these have influenced their personality and their current relationship patterns. Also, how their current relationship patterns affect their symptoms. In terms of engaging those who are not quite on board, I have developed a stock of various stories about the link between feelings and physical symptoms. Making links about the meaning of the symptoms, such as “I wonder if this pain could be the pain of losing your mother?” or “your body seems to be saying – no, I can’t do this any more – even if you can’t say no verbally”. Stress has a lot to answer for and can be called upon as a direct link with muscle tension, tiredness, the immune system etc. Shellshock, the physical symptoms presented by soldiers in the first world war can be used to explain how severe some psychosomatic reactions can be. One patient I discussed this with was amazed, she said “I have been telling my friends for years that I was shell-shocked by my childhood”. The CAT approach, which focuses more on the story of the patient’s whole life, rather than on their current symptoms, also seems to allow the possibility of links to emerge between the psychological and the physical more easily.

It is often worth asking to see the person with their partner as part of this initial assessment. The partner may be more psychologically minded than the patient, and more aware of the stress the patient is under. There have been several patients for whom it felt vital to have the partner in as part of the therapy, doing a kind of hybrid between individual therapy informed by the presence of the partner, and couple therapy.

Reciprocal Role Relationships with the body

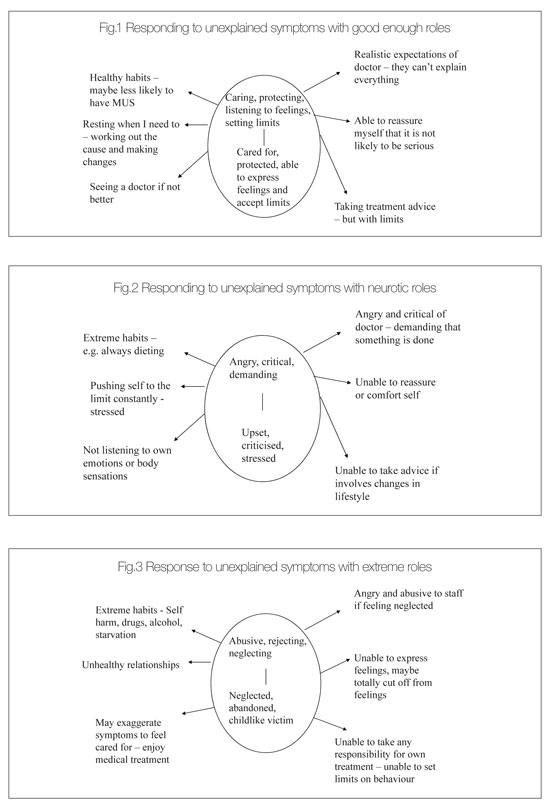

One way of thinking about physical symptoms is that they are a message from the body that something is not quite right. If we have a good relationship with ourselves, including our body, then we will pay attention to these messages. Hopefully, we will spend a bit of time and attention trying to figure out what we may have done to cause the symptom – did I sit for too long in one position/ push myself too hard at the gym/ wear those new shoes for too long? We may talk about the problem to our nearest and dearest and get their ideas, which may well be more honest and objective than our own. Because we care about ourselves, we will try and make small changes so that our body has a chance to recover. If we still cannot figure it out, we may go and see a doctor, but with good enough reciprocal role patterns, we will have a realistic expectation of what can be done and a willingness to take responsibility for the advice we are given (see fig 1).

If we have more of a neurotic pattern of reciprocal roles, for example a strong streak of critical and demanding to criticised and not good enough, we may have a different reaction to our symptoms. We may already be pushing ourselves very hard, constantly dieting, constantly exercising, which may lead to an increasing number of physical problems. It may be impossible to think calmly and compassionately about the cause of our symptoms as we are just cross with our body for letting us down. I had one patient who said “I hate my body, it always lets me down. Once it starts behaving itself, then I will take care of it better!” Such a patient may be very demanding and critical of health staff and so not get the help or advice they need. They may find it very hard to rest for long enough to fully recover, or to pace their activity during their recovery, doing too much and so relapsing every time (see fig 2).

The third group of patients are those who have more extreme reciprocal roles, particularly those of abuse, neglect and rejection. These patients may treat themselves very badly indeed, not eating properly, self harming, and generally punishing and abusing themselves. They may find it very hard to be honest about these behaviours and so avoid doctors, or tell only half the story so the clinicians are left feeling confused and suspicious. For these patients, getting attention and care in hospital may feel like a dream come true when their other relationships are so full of conflict. When they are criticised or confronted with certain behaviours, they may react with extreme emotions and become distraught or very angry with the treating team. Having never had an early relationships in which their thoughts and feelings were listened to or valued, they may have no way of doing that for themselves and may genuinely feel emotions only as bodily sensations (see fig 3).

Thus in assessing patients, I am constantly listening out for these kind of relationships with the body, the symptoms, with the patient’s carers or their clinicians and offering up possible links for reflection. I will aim to include these in the reformulation letter and also in the diagram.

Initial Outcomes

I decided as my initial measure of effectiveness that I would use before and after CORE scores. Of my first 10 patients (9 female, 1 male) with medically unexplained symptoms of a mixture of types, who engaged in individual CAT, 3 dropped out of therapy (30%). This feels like quite a high drop out rate and I think reflects partly the ambivalence these patients have about a psychological treatment for physical symptoms, but also the very real practical difficulties for disabled patients have in terms of being able to travel, in terms of their finances, and just being able to get to the therapy.

If we look at the results for those patients who did complete a 16 session CAT, one patient had a CORE score which was unchanged at the end of therapy. The other 6 patients all had CORE scores which were reduced at the end of therapy (average CORE score at start of therapy 53.8, average CORE score at completion of therapy 23).

Conclusion

Cognitive Analytic Therapy appears to be an acceptable therapy for people who are presenting with medically unexplained symptoms and this early work indicates that it may be effective. It offers an alternative to CBT for patients who wish to look at their past life experiences as part of making sense of their current symptoms, and for patients who present with significant relationship difficulties as part of the picture.

References

Fosbury, J. et al (1997) A trial of CAT in poorly controlled type 1 diabetes patients. Diabetes Care, 20, 6, pp 959-964.

Gill, D.& Bass, C. (1997) Somatoform and Dissociative disorders: assessment and treatment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, vol.3, pp 9-16.

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes. Reformulation, Winter, pp.53-55.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Audit of Factors Predicting Drop Out from Cognitive Analytic Therapy Kerrie Channer and Alison

Channer, K., Jenaway, A., 2015. Audit of Factors Predicting Drop Out from Cognitive Analytic Therapy Kerrie Channer and Alison. Reformulation, Winter, pp.33-35.

Words for Feelings

Elizabeth Wilde McCormick, 2019. Words for Feelings. Reformulation, Summer, p.32.

The Launch of a new Special Interest Group

Jenaway, Dr A., Sachar, A. and Mangwana, S., 2011. The Launch of a new Special Interest Group. Reformulation, Winter, p.57.

Psycho-Social Checklist

-, 2004. Psycho-Social Checklist. Reformulation, Autumn, p.28.

What’s in a name? The power of power, narrative, and naming things that are so numerous we no longer see them

Louise Kenward, 2020. What’s in a name? The power of power, narrative, and naming things that are so numerous we no longer see them. Reformulation, Summer, pp.35-37.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

Aims and Scope of Reformulation

Lloyd, J., Ryle, A., Hepple, J. and Nehmad, A., 2011. Aims and Scope of Reformulation. Reformulation, Winter, p.64.

Black and White Thinking: Using CAT to think about Race in the Therapeutic Space

Brown, H. and Msebele, N., 2011. Black and White Thinking: Using CAT to think about Race in the Therapeutic Space. Reformulation, Winter, pp.58-62.

Book Review: "Why love matters – How affection shapes the baby’s brain" by Sue Gerhardt

Poggioli, M., 2011. Book Review: "Why love matters – How affection shapes the baby’s brain" by Sue Gerhardt. Reformulation, Winter, p.43.

CAT, Metaphor and Pictures

Turner, J., 2011. CAT, Metaphor and Pictures. Reformulation, Winter, pp.39-43.

Comment on James Turner’s article on Verbal and Pictorial Metaphor in CAT

Hughes, R., 2011. Comment on James Turner’s article on Verbal and Pictorial Metaphor in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.24-25.

Compassion in CAT

Wilde McCormick, E., 2011. Compassion in CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.32-38.

Equality, Inequality and Reciprocal Roles

Toye, J., 2011. Equality, Inequality and Reciprocal Roles. Reformulation, Winter, pp.44-48.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Hepple, J., 2011. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Winter, p.4.

Letter from the Editors

Lloyd, J., Ryle, A., Hepple, J. and Nehmad, A., 2011. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Winter, p.3.

Supervision Requirements across the Organisation

Jevon, M., 2011. Supervision Requirements across the Organisation. Reformulation, Winter, pp.62-63.

The Chicken and the Egg

Hepple, J., 2011. The Chicken and the Egg. Reformulation, Winter, p.19.

The Launch of a new Special Interest Group

Jenaway, Dr A., Sachar, A. and Mangwana, S., 2011. The Launch of a new Special Interest Group. Reformulation, Winter, p.57.

The PSQ Italian Standardisation

Fiorani, C. and Poggioli, M., 2011. The PSQ Italian Standardisation. Reformulation, Winter, pp.49-52.

The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview

Yabsley, S., 2011. The Reformulation '16 plus one' Interview. Reformulation, Winter, p.67.

Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy for Medically Unexplained Symptoms – some theory and initial outcomes. Reformulation, Winter, pp.53-55.

What are the important ingredients of a CAT goodbye letter?

Turpin, C., Adu-White, D., Barnes, P., Chalmers-Woods, R., Delisser, C., Dudley, J. and Mesbahi, M., 2011. What are the important ingredients of a CAT goodbye letter?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.30-31.

Whose Reformulation is it Anyway?

Jenaway, Dr A., 2011. Whose Reformulation is it Anyway?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.26-29.

Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities

Frain, H., 2011. Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

"They have behaviour, we have relationships?"

Greenhill, B., 2011. "They have behaviour, we have relationships?". Reformulation, Winter, pp.10-15.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.