The Application of CAT to Working with People with Learning Disabilities

Moss, A., 2007. The Application of CAT to Working with People with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-27.

CAT has provided a usable working model for clinicians in a variety of settings. This article illustrates the application of CAT within the context of working with people with learning disabilities and their support system. It explores the theoretical underpinnings of how CAT can be applied within this context, and provides clinical examples and ref lections of the use of CAT within an individual and systemic framework.

Introduction

CAT as a model for addressing psychological distress is a flexible model which has been applied to a range of clinical problems and within different settings. Whilst the application of CAT within learning disability settings is a fairly new occurrence, it has provided a framework within which to develop interventions at an individual and systemic level. Currently, the model’s application is being applied largely through individual clinician’s creativity, and has shown some promising indicators, proving to be an effective method of intervening. The model’s application in this setting still requires formal evaluation, and is therefore an area for future research.

This article will aim to look at how the theoretical understandings of CAT underpin common themes in the presentation of people with learning disabilities, particularly looking at the development of the self. Following this, I aim to address how CAT can be used on both an individual and contextual level. My own clinical examples on working at these different levels will be used to illustrate the benefits of using a CAT approach as well as identifying some barriers to it’s effectiveness.

The development of the self

CAT thinking regarding how individuals’ internalise and fully adopt patterns of being, (in CAT terms, reciprocal roles) has largely been informed from Kleinian Object Relations and Vygotskian activity theory. Ryle (1991) explained how these two schools of thought could be integrated in the idea of multiple roles which arise initially from the primary carers’ relationships with the infant. Ryle drew from Kleinian thinking in how the infant relates to the mother in terms of ‘objects’. However, in CAT, these objects are more than mental representations for the child, the child’s sense of self is actually constituted by these early socially meaningful experiences. The child learns to predict the responses of the caregiver as a consequence of his/ her actions, and as a result begins to generate a number of reciprocal responses to their caregiver (i.e. compliant child to controlling mother, neglected child to neglecting mother). Consequently, the child learns both poles of the reciprocal relationship, i.e one self and one other (parental) derived. Eventually the child internalises both these roles, ie. in Vygotskian thinking, this relationship is internalised by the infant in the form of ‘voices’. Consequently, as the child develops into adulthood they learn to inhabit and shift between the two roles, thus creating their own reciprocal role procedures. Bakhtin (1986) adds to this concept in elaborating how these voices form dialogues between actors. These include the voice of the child and the parental voice and a third voice which represents the views of the wider cultural and societal beliefs and values, the parental voice being in effect the conduit for this.

The context in which the individual resides is of particular relevance in how individuals with learning disabilities develop their sense of self and the reciprocal roles they find themselves operating within. The history of how people with learning disabilities have been regarded and treated as a distinct group must be taken into account when attempting to understand the origins of their reciprocal role repertoires. These repertoires can be clearly linked to the historical legacy of marginalizing such people through fear and ignorance. The pejorative names used to refer to people with learning disabilities and their experience of being shut out of society in institutions, is a clear sign of how they were regarded by their immediate families and wider communities. Their vulnerability has often led them into reciprocal roles of being abused by those with greater power.

Whilst overtly abusive experiences are increasingly challenged, more subversive roles still exist as people continue to struggle to value and respect people of differing abilities. The often observed interactions of not being heard or understood, being infantilised and overprotected, all emphasise a continued inhibition of healthy relating.

The reciprocal roles which emerge from this form of relating are supported by King (2005) and Psaila & Crowley (2005), who found in working with this client group, recurrent roles of contemptuous to contemptible, neglecting to deprived, rejecting to rejected, abandoning to abandoned.

Through my own CAT training, I have begun to reflect on the experience of people with learning disabilities’ often restricted and at times punitive interactions as inhibiting a lack of mutually beneficial reciprocation which will inhibit the individual’s sense of self and social identity. I have often seen in clinical practice how the individual with learning disabilities often fails to be offered meaningful interaction which inhibits the development of healthy dialogues. Those around them are often out of the individual’s ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD), (Vygotsky, 1978), in how they interact. Other’s communication can show ignorance of the individual’s cognitive abilities, making the assumption, “they understand everything I say”, or “they understand little”. This can be observed in either failing to adjust the method or complexity of the communication or in avoiding communication. CAT theory explains how our sense of self is mediated by the actions of others, so if the individual’s relational context is impoverished or overly restrictive, it is easy to understand how the individual with learning disabilities develops a restricted sense of self. This has been termed as a ‘false self ’ (Ryle and Kerr, 2002, p57), as the individual becomes overly dependant on the responses of others through not being given adequate scaffolding for personal development. A common legacy of the deprived and emotionally neglectful learning disability institutions is reflected in the ‘institutional smile’, as the individual presents a mask-like happy front in order to comply with social norms. Here the individual has become ‘out of dialogue’ with their authentic feelings.

Using dialogical understandings in relation to working individually with people with learning disabilities

For a number of individual’s with learning disabilities their internal dialogues are readily accessible, as they speak openly in dialogue with themselves, for instance in speaking in the third person as they comment on their own behaviour. Vygotsky may have understood this as a reflection of beginning the process of internalizing an external/social dialogue, as he regarded such ‘ego-centric’ speech in children as ‘thinking aloud by talking to oneself ’ (thus taking a developmental approach to how we internalize diaologue). Such a process plants the seeds for being able to think abstractly (and self reflect) rather than merely react to our immediate environment. In CAT terms, this is described as ones ability to self reflect and other reflect rather than purely ‘being in’ the states and reciprocal relationships. This ability to self reflect is stated by Ryle and Kerr (2002), to result in an, “empathic, imaginative understanding of others, a theory of mind by the age of three to four years”. Developmentally people with learning disabilities may not fully attain such a theory of mind, and the absence of such is indeed one of the cornerstones for a diagnosis of autism. They may appear ‘stuck’ in engaging in the development phase of thinking aloud, and can often be witnessed to lack self reflection. This deficit can often be seen to be accompanied by a poor emotional vocabulary, which begs the question, “does increasing an individual’s emotional vocabulary and understanding, increase their ability to be in dialogue with themselves and self reflect?”

Whilst anecdotally those involved in the lives of people with learning disabilities readily accept the individual with overt selftalk, as merely engaging in verbal commentating, this behaviour can sometimes be misconstrued as a symptom of psychosis. A clinical example of my own illustrates this point in working with a young female who was withdrawing from those around and queried to be engaging in self harm. Initially it was felt by the referrer that her mental health was deteriorating as she would be found to speak openly to a non-existent other, and would injure herself on occasion by hitting hard surfaces. Through assessment, it was hypothesized that due to the dynamic readily acknowledged by even her mother, she was engaged in a reciprocal role of being controlled in relation to a controlling mother. Reports from the day service she attended were able to support this in her frequent retiring to a locked cubicle toilet where she would engage in ‘angry conversations’ with herself, taking the dominant role in reprimanding herself. At such times, her agitation in this dialogue could reach such a pitch where she began to hit or kick out. Interestingly, in her interactions with others she could be seen to display a controlling dynamic by withholding her input, (one of the few methods of control she had at her disposal given her disempowered status). She did this by failing to respond to questions it was clear she knew the answer to, or resisting activities she was encouraged to do. Clearly the concept of ‘control’ was in her dialogue as she could verbalise it and take it’s role when alone or present a ‘controlling’ stance in her resistance. It was understood that this was a response to the controlling environment she had been subjected to, in order to retain a sense of self. Unfortunately, her sense of self had not been able to develop sufficiently to overcome the controlling dynamic she experienced, such that she found it incredibly difficult to make choices or assert her wishes. She showed this in her frequent statements of, “mum won’t let me”.

I saw her use of withdrawing interaction as a primitive expression of disavowed feelings of autonomy. In addition, I understood her physical aggression whilst on her own, as disavowed expressions of anger. Whilst her support network saw these expressions as problematic, it is often more useful to view such behaviours as merely symptoms of problematic experiences. These problematic experiences can be seen to emerge from what Stiles (1997) termed ‘suppressed voices’ which can only gain expression through primitive expressions.

The use of words as therapeutically enabling

Therapy was aimed at creating a new dialogue for her where she was encouraged to assert her wishes in open dialogue. The client during assessment was found to struggle with a consistent understanding of basic emotions, teaching an emotional vocabulary was therefore imperative in beginning to develop a narrative. Work then progressed to encouraging expressions of autonomy and choice and developing a sense of self, by expressing personal preferences. In doing this, the Vygotskian understanding of scaffolding was used to help her internalise more adaptive voices. Initially her actions were labeled, i.e. “you’re looking at your watch, it seems you want to finish our session”, to her being encouraged to state the words, “please leave now”. Through therapeutic relating, the suppressed dialogue was brought into conscious dialogue, between therapist and client, but this reflective activity eventually becoming intrapersonal, and adapted to provide a new dialogue of selfassertion and control.

In my work, I have become increasingly conscious of the words I use to signify the various roles an individual may be reflecting in their presentation and what appears to be elicited in others. Often individuals with learning disabilities cannot provide their own words for the roles they are engaged in. When identifying words for roles, they may seem harsh or unconfirmed. It has been important to retain the ‘hypothetical’ or debatable nature of the chosen roles particularly when sharing reformulations with those who are involved in reciprocating or identifying with such roles with the client, as they may appear punitive and blaming. The collaborative stance CAT encourages is therefore brought to the fore in deciding on such roles and resultant procedures, and thus guards against distancing the ‘client’ (i.e the individual or the system they’re involved in) from the therapist, thus maintaining the alliance.

It is important to emphasise a non-blaming stance towards those who may appear instrumental in the development and maintenance of maladaptive roles and voices which the client has internalized. This was particularly relevant in the above case so as not to alienate the mother, and to create an ally to maintain and develop the work already begun. Leiman (1993), assists this approach in stating that the internalized roles/ voices are not merely a reproduction of the external figures but “a joint creation of two interacting subjects”. In the process of internalization, the individual has created a ‘new’ voice, carrying with it the meanings ascribed by how the individual experienced the relationship. In this way, we can see that a ‘controlling mother’ does not exist without the individual who is being ‘controlled’, and so the voice does not exist outside of the ‘controlled relationship’ which has been created. This enables the individual not to be seen as ‘controlling’ per se, merely the relationship as controlling. Onus for the maladaptive dynamic is therefore given to both parties in an externalizing way which avoids blaming and personalising.

In order to transform maladaptive patterns it is necessary to begin somewhere and so words are offered as a way of beginning the dialogue. It is up to the parties involved to engage in the dialogue and adapt words as they resonate more fully with their felt experience. Here the work of Hobson (1985) appears useful, as a conversational approach can be seen as an exploratory dialogue which facilitates change. Hobson however not only advocates the use of the spoken word to uncover the felt experience but also gesture, drawing, and other non-verbal signs as a ‘way in’ to the individual’s subjective experience. This is of particular relevance when working with people with learning disabilities who may have limited verbal expression.

The benefits of CAT principles to guide individual/direct working

Personal experience of using CAT individually with clients has revealed an understanding of it’s ability in empowering the individual. This occurs through a jointly created understanding of problematic procedures through their active participation. This is enabled by CAT’s use of transparent methods of reformulation – only that which has been discussed or expressed is used to inform an understanding of how the problems have been created and are maintained. The use of diagrams and pictorial representations further adds to the transparency as it overcomes any barriers in language.

People with learning disabilities often struggle with a lower attention span and memory. The use of a mutually understandable sequential diagrammatic reformulation (SDR) means the most important aspects are focused on and revisited thus becoming incorporated into long term memory. The ability to use the ‘here and now’ therapeutic relationship to inform patterns of how the client relates to others, further reduces the load on memory. This additionally avoids the need for more abstract or hypothetical discussions which may be out of the client’s ZPD.

Due to the collaborative nature of the therapeutic encounter, the client can engage in more adult relationships, warding against the therapist taking the ‘rescuing’ or ‘all powerful/ knowing’ role, regularly elicited from clients in disempowered roles.

In discussing difficulties, the use of relating these in nonblaming ways (i.e via the SDR, and as an understandable response to negative experiences), can further encourage more adult relating, as the individual is likely to have an entrenched experience of feeling shamed and in a powerless role as they have repetitive experiences of failure.

The nature of termination is addressed at an early point. This is particularly relevant for people with learning disabilities who are often excluded from preparations to loss, (i.e. from engaging fully in grief and mourning rituals) and who experience repeated losses, (i.e. from transitory staff groups, and moving living arrangements), having little control on how these are managed. CAT allows clear opportunities to allow the client to explore their feelings in relation to ending therapy, and can be made concrete by naming and even crossing out the sessions diagrammatically each time. In this way the client has a reparative experience of preparing and successfully negotiating an ending.

The role of context

Individual CAT may sometimes be inappropriate when a working alliance cannot easily be achieved. The working alliance being the joint ability between therapist and client to set goals, agree on tasks and develop a human relationship or bond (Bordin, 1979). This can often be overcome by ensuring the work is within the clients ZPD, which can include adapting the CAT tools as described by King (2002).

If it is not possible to use direct CAT with a client, CAT principles can still be applied elsewhere in the system. Given the long-term nature of the relationship experienced by someone with learning disabilities with providers of their social care, the interactions which occur as a result are likely to be highly important in understanding the reciprocal roles most prevalent for that individual.

Walsh et al (2000) highlighted how any relationship which holds certain parental characteristics (i.e. differential levels of dependency, power or emotional vulnerability), which surely exists between clients and support staff, can be understood in object relational terms. This indicates how powerful, enduring and influential such relationships are to the client involved in such a dynamic.

How services maintain dialogical conversations of power

In my experience in working in the field of learning disabilities, I can give no personal example of a system referring itself for support. The issues are invariably located in the individual the system is struggling to support. The referrals are often clustered under the rubric of ‘challenging behaviour’, (i.e. problematic behaviours which places the individual or others at risk and /or prevent access to community facilities). Here the system’s method of referring can be seen as enacting a role of rescuing or ‘all powerful’.

It is also important to attend to the dialogue we engage in as services responding to such referrals, as we adopt a position of dominance/power in accepting referrals which are couched in the notion of the individual requiring support, rather than the system. This surely perpetuates the role carers inhabit as they bring the individual to be ‘cured’ to therapy. CAT offers new methods of relating as it’s collaborative approach addresses power imbalances by ‘working alongside’ an individual.

Procedures can be identified which involve the interplay of the individual in their support system, and thus shares responsibility to all elements of the system rather than locating the issue in the individual. Emerson & Hatton (2001) note that challenging behaviours often serve as a function to re-establish ‘control’ for the individual (i.e. terminating unwanted contact or activities), or as a method of eliciting care from support staff. It can therefore be seen how this behaviour can be conceptualized as the client’s transference in response to reciprocal roles they have adopted.

It has long been acknowledged that ‘challenging behaviour’ in learning disability settings, have strong environmental determinants. As Emerson (2001), stated, “violent behaviour is likely to be intimately connected to the social environment (which includes the beliefs, attitudes and behaviour of social care workers)”. Emerson & Hatton (2001), illustrated how the combined responses of the system around the individual who challenges can be highly damaging. This includes the individual experiencing abuse, (Rusch et al, 1986), inappropriate treatment, i.e. the prescription of non-indicated medications, (Davis et al, 1998), exclusion from community based services, (Borthwick- Duffy et al. 1987), deprivation and systematic neglect, (Emerson & Hatton, 1994). All these responses naturally reinforce the likelihood of challenging behaviour occurring. The triggers and consequences of challenging behaviour can therefore be conceptualized as reciprocal role procedures between the client and their support system, namely around issues of control and punishment.

Such research findings indicate greater focus on the system to reduce instances of challenging behaviour. Ryle and Kerr (2002), identified that the system in which the person operates can itself become caught up in reciprocating or identifying with the individual’s role enactments and in so doing both re-enact previous maladaptive patterns.

Lloyd and Williams (2004), identified five key reciprocal roles, (persecuting/persecuted, ideally caring/ideally cared for, rejecting/rejected, punishing/punished, controlling/compliant), and resultant procedures which learning disability staff commonly find themselves in relation to those they support. Thus perpetuating previous harsh roles the client has experienced.

All staff need not inhabit the same roles as they identify or reciprocate with the client’s enactments. If the roles which different staff members enact are particularly polarized (i.e those enacting ‘ideal care’ versus those more allied to ‘punishment’) this can result in staff splitting. Some may identify with the client’s plight and move to a rescuing role, becoming over-involved beyond professional boundaries, whilst others may adopt a reciprocating rejecting role (through a sense of hopelessness and frustration as they perceive the client to be sabotaging or overly demanding). As staff hold rigidly to their roles they are likely to criticize those that hold an opposing role. This ‘splitting’ often results in staff burnout through high levels of stress. In addition, the client may be left in a state of confusion as they receive mixed messages from their support system, resulting in feeling uncontained and likely to resort to further challenging behaviour.

Working at the staff level thus creates opportunities to pre-empt the breakdown of a support system, avoiding the perpetuation of further experiences of loss and rejection for the client.

The use of contextual reformulations to re-adjust maladaptive service responses

My own work with individuals referred to the service for challenging behaviour has involved a growing emphasis on contextual reformulations and interventions, working alongside support teams to understand why a referred client is presenting as they are and assisting support staff to adopt more psychological approaches in their roles.

I have found it useful to adopt Carradice’s model (2004), of staff consultation within a CAT framework, to recruit the members of the system in addressing their difficulties. The model advocates a process of allowing staff ventilation of feelings, providing a theoretical understanding of their distress to depersonalize their reactions, drawing an SDR through collaboratively drawing patterns of their experiences with the client and finally drawing out staff ’s ideas for exits.

A clinical example of my own illustrates the above process, working with a man who had a long history of self-harm, fire-setting, aggressive outbursts, and absconding. He had experienced numerous staff groups who became increasingly punitive and controlling in their responses. This merely escalated the man’s behaviour, becoming more difficult to manage. The client found it difficult to engage, and would dip in and out of therapy. I viewed this as a clear reflection of a reciprocal role he was enacting through his very chaotic close family relationships where they would show interest and then repeatedly let him down.

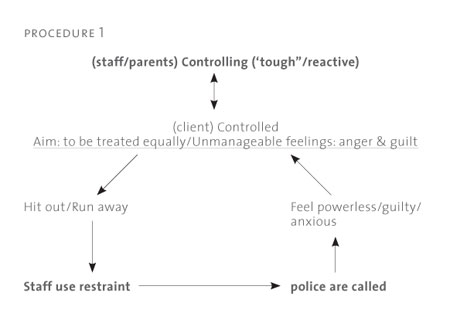

Through consultation and individual work a ‘controlling’ procedure could be described (Appendix 1, figure 1). It was revealed how staff were continuing to react to the client’s behaviour as previous staff groups had. In doing this an assumption could be derived which led them into these behaviours of: “either I’m fully in control or out of control”. This assumption worked equally well for both staff and the client. As a result a trap was identified where staff reacted to any instances of anger by being overly controlling. In response, the client’s anger escalated, with the negative consequences of being restrained or involvement from the police. This was understood to result in confirming to both the client and staff that he was dangerous and risky, and therefore required this level of control.

The exits included staff acknowledging their feelings of control and fear and encouraging negotiation, problem solving and role playing. Given the client’s deficits in problem solving, the staff team began to provide alternatives and consequences for the client to then decide on a course of action. This had the effect of working within his ZPD whilst avoiding a controlling dynamic and relating in a more adult relationship.

In addition, it was deemed important to give him space when experiencing increased agitation. This encouraged the client to learn that carers would not respond in ‘extreme’ ways, i.e. calling the police, and thus helped him maintain self-esteem. Finally he was taught anger management strategies (i.e. asking for space, using relaxation techniques), enabling him to control his anger autonomously. His adoption of these techniques highlighted how his support network had scaffolded his learning from providing direct input, to prompting and eventually being internalised by the client.

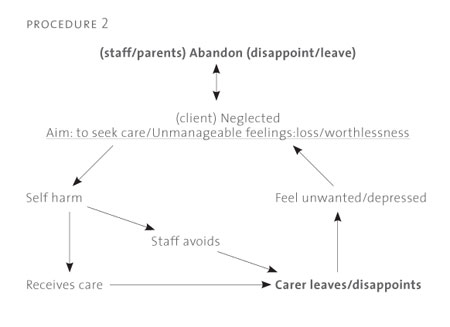

The second procedure was elaborated by some brief individual work with the client around his self harming behaviour, (Appendix 1, figure 2). He was able to describe how he felt either completely cared for or rejected. This was notable in how his family interacted with him, yet his clear idealising of his wish to live with them which he felt would solve all of his problems. In our work it was evident how he engaged in self harm in order to seek care, (illustrated in his wish for people to notice him, or to be treated as special in hospital). Staff consultation was able to identify their responses to this behaviour in how they became highly anxious and saw him as highly risky. They either withdrew or give care. The care was however only of short duration, in effect letting the client down, which merely confirmed the client’s expectations.

Exits were identified by staff in acknowledging the client’s sensitivity to loss and disappointment and providing consistent and appropriately boundaried care. This included following through with requests and promises in order to build trust. In this way the client could learn that he could receive care through means other than self harm.

Follow up indicated that the client was able to actively use his strategies to request space when he began to feel anxious. He indicated a greater level of trust between him and staff in his ability to turn to them to discuss problems, rather than engage in his previous risky behaviours. Even though the client continued to engage in certain boundary testing behaviours, the staff maintained their consistent responses, i.e. not immediately calling the police when he absconded. As a result the numbers of reported incidents dramatically reduced, and the client showed a good ability to respect the boundaries which were necessary for his safety.

Strengths of contextual reformulations in learning disability settings

A number of benefits to using contextual reformulations can be identified as follows:

It’s ability to re-conceptualise the client’s difficulties into a coping mechanism developed to meet core unmet human needs. This has the result of diffusing the often damaging countertransference responses by the staff, which often include staff ’s assumptions that the behaviour is ‘manipulative’ or ‘attention seeking’.

The use of the SDR in mapping out the system, enables a non-judgemental understanding of the causes of negative behaviours. This allows staff not to personalize their reactions, allowing for open expression and working through of countertransferential responses. This prevents staff becoming stuck in collusive cycles of reacting to difficult behaviours.

CAT can re-interpret often complex patterns into understandable and accessible ways, to assist all staff, regardless of differing levels of intellect, in how they relate on a daily level with their clients.

This allows staff to develop their own ‘exits’ from unhelpful procedures. With this comes greater ownership and less likelihood of the interventions being rejected as ‘unworkable’. Rejection of interventions may otherwise occur through a countertransference response to an ‘expert’ dipping in to ‘solve’ the problem, or through the advice not being rooted in practical considerations, out of ignorance of the available resources of the system.

It allows intervention to be targeted at a number of levels in the system, (individual, to staff team, to management and organizational levels), depending on the most effective point of entry into the system.

It develops a shared understanding of the problem. This allows for greater staff cohesion and containment for both the staff and the client, as mixed messages, and the prospect of staff splitting are avoided.

Limitations of contextual applications of CAT

It is not always easy to see where it is best to make an impact within the system. This is due to confusions as to where the problem really lies, or the parts of the system that are most influential in maintaining maladaptive procedures. This is particularly difficult when the power dynamic is stacked against the individual with learning disabilities, and others in the system may wish to avoid their role in the difficulties.

Even though staff engaged in the work may be willing to create change, they may be powerless to have a long-lasting impact. Long-term change may be predicated by the motivation of those in more powerful senior positions to implement necessary organizational changes.

The nature of staff teams in these settings is inherently one of frequent change. Finding a good working alliance and agreement to follow through with interventions may not mean long-standing change if key staff members leave the service. The ability to provide regular review and further training sessions thus becomes an issue.

If all of those involved in the client’s care are not involved in the process, unhelpful dynamics can still continue to be played out, sabotaging any good work that others have achieved. This is particularly difficult to achieve when a client often requires 24 hours support and there are not available supplementary staff to draw on to cover staff ’s participation in the process.

Conclusion

Using a CAT approach within learning disability settings, whilst a relatively new mode of working for myself, highlights it’s strengths in a field which demands the integration of developmental and contextual influences on the client. The use of working alongside the client in a truly collaborative way addresses the stark power imbalances that are often prevalent in the lived experience of people with learning disabilities. CAT’s method of appraising difficulties as observable and transparent attempts to address unmet needs, has assisted me in representing difficulties in non-blaming ways, again a necessary element of the reparative work for all involved in these systems.

Both individual and contextual CAT approaches make it easy to understand the required exits which develop from the recognition phase of reformulation, which demystifies the ‘expert’ role of professionals driven to offer interventions. In so doing, the gains are owned and maintained by those integral to the development of the individual. This approach offers a new way of working from traditional long-term assessment intensive approaches of understanding an individual’s presentation. This is a crucial element in a context where results are required quickly both for the individual requiring support and in an increasingly resource stretched NHS. I look forward to the increasing knowledge base and developments from using CAT in this context.

Andrew Moss

References

Bakhtin, M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. Edited by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holoquist. Austin. University of Texas Press.

Bordin, E.S. (1979). The generalisability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy, Theory, Research and Practice, 16, 252-260.

Borthwick-Duffy, S.A., Eyman, R.K., & White, J.F. (1987). Client characteristics and residential placement patterns. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 92, 24-30. Carradice, A. (2004). Applying Cognitive Analytic Therapy to guide indirect working. Reformulation, theory and practice in CAT, 23, 16-23.

Davis, S., Wehmeyer, M.L., Board, J.P., Fox, S., Maher, F., & Roberts, B. (1998). Interdisciplinary teams. In S. Reiss & M.G. Aman (Eds.). Psychotropic Medication and Developmental Disabilities: The International Consensus Handbook, p133-150. Ohio: Nisonger Center, Ohio State University.

Dunn, M. (1993). Some subjective ideas on the nature of objects. A.C.A.T. Newsletter, Nr. 2, 16-17, London, UK, November 1993.

Emerson, E. & Hatton, C. (1994). Moving Out: The effect of the move from hospital to community of the quality of life of people with learning disabilitites. London. HMSO.

Emerson, E. & Hatton, C. (2001). Violence against social care workers supporting people with learning difficulties: A review. NISW Briefing Number 26: Violence Against Social Care Workers.

Hobson, R. (1985). Forms of feeling: The heart of psychotherapy. Tavistock Publications, London.

King, R.A. (2005). CAT, the therapeutic relationship and working with people with learning disability. ACAT online reference library.

Leiman, M. (1993). Words as Interpsychological Mediators of Psychotherapeutic Discourse. Paper presented at the Semiosis in Psychotherapy Symposium, 6/9/93, Valamo Monastery, Finland.

Lloyd, J. & Williams, B. (2004). Exploring the use of cognitive analytic therapy within services for people with learning disabilities and challenging behaviour. Clinical Psychology and People with Learning Disabilities, Vol 2, Issue 3, 20-22.

Psaila, C.L. & Crowley, V. (2005). Cognitive Analytic Therapy in People with Learning Disabilities: An investigation into the common Reciprocal Roles found within this client group. Mental Health and Learning Disabilities: Research and Practice. 2 (2), 96-108.

Rusch, R.G., Hall, J.C., & Griffin, H.C. (1986). Abuse provoking characteristics of institutionalized mentally retarded individuals. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 90, 618-624

Ryle, A. (1991). Object relations theory and activity theory: A proposed link by way of the procedural sequence model. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 64, 307-316.

Ryle, A. (1994) Projective identification: A particular form of reciprocal role procedure. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 67, 107-114.

Ryle, A, & Kerr, I. (2002). Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Principles and Practice. Wiley. Stiles, W.(1997). Signs and voices: Joining a conversation in progress. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70, 169-176.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Walsh, S. Hagan, T & Gamsu, D. (2000). Rescuer and rescued: Applying a cognitive analytic perspective to explore the ‘mis-management’ of asthma. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 73, 151-168.

Appendix 1

Figure 1 :

‘Controlling’ Target Problem Procedure for contextual reformulation. (Staff ’s response in bold type).

Figure 2 :

‘Seeking Care’ Target Problem Procedure for

contextual reformulation. (Staff ’s response in

bold type).

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!

Petition to NHS England - The Case for Funding Training in the NHS 2021

Alert!ACAT's online payment system has been updated - click for more information

Full Reference

Moss, A., 2007. The Application of CAT to Working with People with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-27.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Thoughts on the Rebel Role: Its Application to Challenging Behaviour in Learning Disability Services

Fisher, C., Harding, C., 2009. Thoughts on the Rebel Role: Its Application to Challenging Behaviour in Learning Disability Services. Reformulation, Summer, pp.4-5.

Helping service users understand and manage the risk: Are we part of the problem?

Crowther, S., 2014. Helping service users understand and manage the risk: Are we part of the problem?. Reformulation, Winter, pp.41-44.

Reciprocal Roles and the 'Unspeakable Known': Exploring CAT within Services for People with Learning Disabilities

Lloyd, J. and Williams, B., 2003. Reciprocal Roles and the 'Unspeakable Known': Exploring CAT within Services for People with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Summer, pp.19-25.

"They have behaviour, we have relationships?"

Greenhill, B., 2011. "They have behaviour, we have relationships?". Reformulation, Winter, pp.10-15.

Applying Cognitive Analytic Therapy to Guide Indirect Working

Carradice, A., 2004. Applying Cognitive Analytic Therapy to Guide Indirect Working. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.18-23.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

Book Review: Just War. Psychology and Terrorism

Collins, S., 2007. Book Review: Just War. Psychology and Terrorism. Reformulation, Summer, pp.18-19.

Case Study on Z not as Impossible as we had Thought

Lloyd, J., 2007. Case Study on Z not as Impossible as we had Thought. Reformulation, Summer, pp.31-39.

Generating Practice-Based Evidence for CAT

Marriott, M. and Kellett, S., 2007. Generating Practice-Based Evidence for CAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.40-42.

Keeping cat alive

Ryle, A., 2007. Keeping cat alive. Reformulation, Summer, pp.4-5.

Reformulating the NHS reforms

Jones, A. and Childs, D., 2007. Reformulating the NHS reforms. Reformulation, Summer, pp.7-10.

The Application of CAT to Working with People with Learning Disabilities

Moss, A., 2007. The Application of CAT to Working with People with Learning Disabilities. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-27.

The Inner Voice Check

Elia, I., 2007. The Inner Voice Check. Reformulation, Summer, pp.28-29.

Using CAT in an assertive outreach team: a reflection on current issues

Falchi, V., 2007. Using CAT in an assertive outreach team: a reflection on current issues. Reformulation, Summer, pp.11-17.

You’re driving me insane: Literature, Lyrics and Drama through CAT eyes for clients and students

Elia, I. and Jenaway, A., 2007. You’re driving me insane: Literature, Lyrics and Drama through CAT eyes for clients and students. Reformulation, Summer, pp.43-44.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.