Developing a Language for the Psychotherapy of Later Life

Hepple, J., 2003. Developing a Language for the Psychotherapy of Later Life. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.10-12.

Context

2003 has been an exciting year for the dissemination of our ideas on the psychotherapy of late life from a CAT perspective. Laura Sutton and myself have been working hard on the 'CAT in old age' book and are pleased to say that it is now in the final press stages, being due out in January 2004. The correct title and reference is:

Cognitive Analytic Therapy in Later Life. A new perspective on old age. Edited by Jason Hepple and Laura Sutton. Publishers: Brünner-Routledge.

There are contributions from Mikael Leiman, Sally-Anne Ennis, Madeleine Loates, Mark Dunn and Ian Robbins. The short paper below gives a flavour of the material covered in the book and the type of presentations that Laura and I have been engaging in over the last year.

Introduction

As Freud famously and perhaps a little unwisely stated at the age of forty nine himself :

"Near or above the age of fifty the elasticity of the mental processes, on which the treatment depends is, as a rule lacking - old people are no longer educable".

(Freud, 1905).

This view has had pervasive negative effects on both the development of a psychotherapy theory that speaks to later life as well as the development of psychological therapy services for older people. On exploring this situation further, it seems to me that there are three main conceptual hurdles to the development of a robust psychotherapy of later life:

1. Ageism

2. The Impairment Model

3 A Child-orientated view of Psychological Development

I will take these individually.

Ageism

"Ageism is a term used to describe a societal pattern of widely held devaluative attitudes and stereotypes about ageing and older people. Like racism and sexism, ageism is presumed to be responsible for social avoidance and segregation, hostile humour, discriminatory practices and policies, and a conviction that elderly individuals are a drain on society".

(Gatz and Pearson 1988, p184).

The above describes the standard view of ageism as a socio-political construct involving negative stereotypes of older people and ageing. From the interpersonal perspective of CAT, however, I would suggest that :

"Ageism does not reside exclusively in the young or indeed the old, but in the psychological relationship between the imagined two. Ageism is a mass ego defence; a projection and introjection of negative beliefs and fears about ageing and death in an attempt to escape the reality of the human condition".

And described as a CAT snag:

" I feel uncertain about the meaning of (my) life and anxious about the future. It seems as if there is no escape from the fact that we all grow old and die without finding meaning to our existence and with others abandoning and ridiculing us as our physical and mental faculties decline. If I am to avoid being preoccupied with fruitless rumination about death, which causes depression and stasis, then I must get on with life. There seems no alternative but to put off the acknowledgement of my own ageing to a point in the future when I am old(er) by using defences based in denial, ("You are only as old as you feel", plastic surgery, idealisation of the power of medical science, etc.). This leaves me disconnected from my self, my life and my development and vulnerable to life events that shatter the illusion of immortality and provide glimpses into the seemingly inevitable despair that lies ahead. As time goes on I must try harder and harder to hold it all together. This ends in exhaustion, anxiety and despair about the future and the futility of my past'.

(Hepple and Sutton, 2004, Chapter 2).

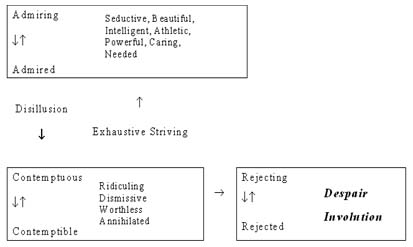

Idealised fantasies of ageing can be described by reciprocal roles such as: Immortal to Admired, Wise to Venerated, Perfectly Caring to Cherished. When disillusion sets in negative roles are uncovered: Contemptuous to Contemptible, Abandoning to Abandoned and Abusing to Abused. 'Reverse Ageism' can be seen as the contemptuous dismissal of the young by the old involving fantasies of the past as the 'golden age' and the relentless negative effects of progress and evolution. Ageism has been slow to reach societal consciousness in the West; perhaps because of the strength of the denial based defence that uses ageist views as a protection against our own mortality. It is perhaps the universality of ageing that has made ageism the 'last great -ism' in Western Society.

The Impairment Model

This is the inevitable extension of the medical or 'organic' model as applied to old age, that looks to disease based explanations of distress, rather than considering individual meaning in the context of a person's own psychological development. Neuropsychology charts deficits and compares older people with 'norms'. It pronounces what a person can no longer do compared with what they should be expected to be able to do. Consider the experience of the average older person in a memory clinic setting to see the power of the model in services for older people in the whole of the health system. In Old Age Psychiatry, patients are often divided into 'organic' (demented) or 'functional' (depressed, anxious or psychotic). There is no category for developmentally and existentially understood distress, except for perhaps the labels 'behavioural' or 'difficult'.

A Child-orientated view of Psychological Development

It is clear that psychoanalytic theory has been obsessed with a child and infant based explanatory model of human development; as if all can be understood as a playing out of unresolved conflicts from early life. While not doubting the power of this model it cannot be a full explanation for distress and uncertainty in later life. Erikson (1963) was the first to really consider psychological development as a life long process continuing into later life, in his extraordinary paper 'The eight ages of man'. Even here, however, the assumed linearity of the stages ending in the 'final conflict' of 'ego-integrity vs. despair', and the emphasis on early development (six of the eight stages) smacks of some internalised negativity towards later life. After his death, Erikson's wife found a loosely described ninth stage; 'transcendency' which may hint at the possibility of hope in old age and the potential for resolution rather than simply the (losing) battle against psychological entropy (despair).

"Despair expresses the feeling that the time is now short, too short to attempt to start another life, and to try out alternate roads to integrity."

(Erikson, 1963, p294).

Where now?

Carl Jung wrote of a ' psychology of life's morning and a psychology of its afternoon', (Jung, 1929, quoted in Garner, 2002, p128), and CAT seems to be in a good position to contribute to the later. CAT is able to offer a truly interpersonal and developmental understanding based on collaborative exploration of an individual client's unique experience, through its conceptualisation of reciprocal roles and dialogue. As Tony Ryle puts it:

"Personality and relationships are not adequately described in terms of objects, conflicts or assumptions, They are sustained through an ongoing conversation with ourselves and with others - a conversation with roots in the past and pointing to the future. In their conversation with their patients, psychotherapists become important participants in this conversation and, CAT, I believe, fosters the particular skills needed to find the words and other signs that patients need."

(Ryle, 2000).

From our work with older people in both the setting of individual therapy and using CAT as a consultation tool for supervision of work with older people, Laura and I have begun to describe theoretical understandings in the following areas:

1. The re-emergence of borderline traits in later life.

2. Narcissism in later life.

3. The retreat into involution and pseudodementia.

4. Delayed trauma in late life.

5. The role play of dementia care.

In the forthcoming book there are chapters devoted to each of these areas with detailed clinical material which brings to life the CAT understanding of late life development. It is beyond the scope of this short paper to do any justice to this material without the detailed clinical exploration of the various contributors. The essence of the approach is to see later life distress as a developmental and interpersonal phenomenon. To give readers a flavour of the style of the work I have included a couple of figures from the talks relating to our developing understanding of narcissism in later life. In Fig 1, King Lear rages at the storm. Unable to sustain his grandiose self in the face of ageing and a loss of his physical and mental powers his narcissistic rage destroys those around him and ultimately himself.

"Pray do not mock me:

I am a very foolish fond old man,

Fourscore and upward…

You do me wrong to take me out o'the grave:

Thou art a soul in bliss: but I am bound

Upon a wheel of fire, that mine own tears

Do scold like molten lead."

King Lear (IV,7)

Fig 2 demonstrates a CAT understanding of later life narcissism: ageing brings with it considerable assaults on the grandiose (admiring to admired) self in those with a narcissistic personality structure. 'Narcissistic' collapse occurs when exhaustive striving is no longer able to generate even brief moments of reciprocated admiration, leading to despair and the experience of potential annihilation of the self. The only safe place to go is further into the shell of 'involution' - rejecting the outside world and attempts at dialogue. It is here that some people retreat into a pseudo-dementia (as did Lear himself) as the final acting out of the humiliated, contemptible self. This sort of developmental understanding allows description of the reciprocal role play at work which gives a framework for the understanding of the client to therapist relationship in such clinical work, which in turn gives hope of non-collusive interaction and therapeutic change. As Winnicott recognised:

"I'm seen or understood to exist by someone. I get back (as a face in the mirror) the evidence I need that I have been recognised as a being".

(Winnicott, 1962).

Conclusion

I hope this brief paper will serve as an invitation to join in the dialogue Laura, myself and others have been having around the neglected field of later life psychotherapy. CAT has much to offer and we await your comments on the book with anticipation.

References

Erikson, E. (1963) Eight ages of man. In: Childhood and society ( 2nd ed.). New York: Norton.

Freud, S. (1905) On Psychotherapy. Standard edition vol. 7. London: Hogarth Press.

Garner J (2002) Psychodynamic work with older adults. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 8: 128-137.

Gatz, M. and Pearson, C.G. (1988) Ageism revised and the provision of psychological services. American Psychologist, 43, 184-188.

Hepple, J. and Sutton, L. Eds. (2004) Cognitive Analytic Therapy in Later Life. A new perspective on old age. Brünner-Routledge.

Ryle, A. (2000) What theory is CAT based on. Origins of CAT. ACAT online. http://www.acat.org.uk (5th October 2000).

Winnicott, D. (1962) Ego integration in child development. In: The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment. London: Hogarth Press.

Full Reference

Hepple, J., 2003. Developing a Language for the Psychotherapy of Later Life. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.10-12.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Book Review: Cognitive Analytic Therapy and Later Life by Sutton and Hepple

Ardern, M., 2004. Book Review: Cognitive Analytic Therapy and Later Life by Sutton and Hepple. Reformulation, Summer, pp.28-29.

CAT in Later Life: Becoming a Historian of the Self

Sutton, L., 1999. CAT in Later Life: Becoming a Historian of the Self. Reformulation, ACAT News Summer, p.x.

Some reflections on the Malaga International CAT Conference "Mental health in a changing world"

Maria-Anne Bernard-Arbuz, 2013. Some reflections on the Malaga International CAT Conference "Mental health in a changing world". Reformulation, Winter, p.50.

Diagrammatic Psychotherapy File

Dunn, M., 2002. Diagrammatic Psychotherapy File. Reformulation, Spring, p.17.

“Resilience in the face of change” – 23rd National ACAT Conference, the benefits of working with over 65s – our reflections on why the evidence base is so limited

Dr Sarah Craven-Staines and Dr Tamsin Williams, 2017. “Resilience in the face of change” – 23rd National ACAT Conference, the benefits of working with over 65s – our reflections on why the evidence base is so limited. Reformulation, Summer, pp.32-33.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

ACATnews: A Fellow Scandinavian's Experience of the CAT Conference in Finland

Burns-Ludgren, E., 2003. ACATnews: A Fellow Scandinavian's Experience of the CAT Conference in Finland. Reformulation, Autumn, p.8.

ACATnews: CAT in Ireland

Parker, I., 2003. ACATnews: CAT in Ireland. Reformulation, Autumn, p.9.

ACATnews: CPD Update

Buckley, M., 2003. ACATnews: CPD Update. Reformulation, Autumn, p.6.

ACATnews: Impressions from the International CAT Conference in Finland, June 2003

Curran, A. and B. Kerr, I., 2003. ACATnews: Impressions from the International CAT Conference in Finland, June 2003. Reformulation, Autumn, p.7.

ACATnews: North-East

Jellema, A., 2003. ACATnews: North-East. Reformulation, Autumn, p.6.

Cultural Diversity and CAT

Toye, J., 2003. Cultural Diversity and CAT. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.25-29.

Developing a Language for the Psychotherapy of Later Life

Hepple, J., 2003. Developing a Language for the Psychotherapy of Later Life. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.10-12.

Editorial

Scott Stewart, M. and Nuttall, S., 2003. Editorial. Reformulation, Autumn, p.2.

History and Use of the SDR

Ryle, A., 2003. History and Use of the SDR. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.18-21.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Potter, S., 2003. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.33-34.

Letters to the Editors: Agenda for Change and Psychotherapy

Nield, C., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Agenda for Change and Psychotherapy. Reformulation, Autumn, p.3.

Letters to the Editors: Association of Adult Psychotherapists (AAP)

Webster, M., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Association of Adult Psychotherapists (AAP). Reformulation, Autumn, pp.3-4.

Letters to the Editors: Dissertations and Reformulation

Toye, J., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Dissertations and Reformulation. Reformulation, Autumn, p.4.

Letters to the Editors: Psychoanalytic Perspective on Perversion Reformulated

Denman, C., 2003. Letters to the Editors: Psychoanalytic Perspective on Perversion Reformulated. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.4-5.

Mind the Gap

Walsh, M., 2003. Mind the Gap. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.22-24.

The States Description Procedure

Ryle, T., 2003. The States Description Procedure. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.13-16.

Using and Understanding of Primary Process Thinking in CAT

Sacks, M., 2003. Using and Understanding of Primary Process Thinking in CAT. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.30-32.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.