Cognitive Analytic Therapy & Dysphagia: using CAT relational mapping when teams can’t swallow our recommendations

Colomb, E. and Lloyd, J., 2012. Cognitive Analytic Therapy & Dysphagia: using CAT relational mapping when teams can’t swallow our recommendations. Reformulation, Winter, pp.24-27.

Dysphagia is a broad term used to describe difficulties with the swallow. It can occur at the oral or pharyngeal (throat) stage of a person’s swallow. The two greatest risks associated with dysphagia are asphyxiation (choking) and aspiration (food or fluid entering the lungs rather than the stomach). Aspiration can lead to chest infections and in severe cases pneumonia.

People with learning disability are at a higher risk of presenting with dysphagia (and other health complaints ) than individuals in the general population (Baker, Oldnall, Birkett, McCluskey and Morris, 2010) and respiratory disease is the leading cause of death for the learning disability population (Hardy, Woodward, Woolard, Tait, 2007).

It is the role of the speech and language therapist (SaLT) to assess the safety of a person’s swallow and make mealtime recommendations, which optimise safety by minimising the risk of aspiration and asphyxiation. Due to the serious nature of dysphagia much of a SaLT’s time can be dedicated to working with clients with eating and drinking difficulties.

A Community Learning Disability Team (in North-East Hampshire and South West Surrey) has a CAT supervision group. Current members are from Community Nursing, Speech Therapy, Music Therapy and Behavioural Support (and have included people from Psychiatry and Occupational Therapy), facilitated by the second author (Julie), who is a clinical psychologist. As you can imagine, a name like ‘CAT’ invited all kinds of jokes as the group thought about what they wanted to call themselves; and the first author (Elly), perhaps aided by her sensitivity to language, came up with ‘CATerpillars’ in which we positioned CAT’s awareness of relationships as ‘one nice green leaf’!* Half of the group worked with both individual clients and the staff teams of those clients and the other half worked exclusively with staff teams and carers.

The first time we worked together pre-dated this group. Both clinical psychology and speech therapy were asked for a capacity to consent (Mental Capacity Act) assessment in which the referral was for the Speech Therapist to assess comprehension and the Psychologist, intelligence. Social Services were attempting to determine whether a young woman, whom they believed had an intellectual disability, could consent to remain living with her mother when her younger sister had been removed and put into the care of the local authority owing to neglect and emotional abuse. On starting this work, we soon found it was obvious that the issues were principally relational rather than language or intellectual. Using CAT’s tool of mapping out reciprocal roles, we based this capacity assessment on describing the relational patterns that were limiting capacity and, in keeping with a focus on relationships, we wrote both the report and a letter to the young adult and the mother in the more intimate style of a Reformulation letter, than a classically more distanced assessment report.

When a place came up in the supervision group, Elly remembered this piece of work and was curious and open minded about using CAT. She did not have a suitable individual case (i.e., someone for whom communication is damaged by emotional problems such as elective mutism), but in discussion we wondered whether CAT could be useful where there are staff problems. Some teams feel toxic in their effects on our work, where they adopt a collusive approach to non-cooperation with professionals invited to advise. These teams increase the risk of non-compliance with meal time recommendations, which might in turn result in serious ill health or even death. In accord with the original vision for CAT in the NHS, in using CAT, Elly is seeking to enhance her Speech and Language Therapy practice.

When working with people with learning disabilities who have dysphagia, much of the post assessment work is carried out with staff teams because many of the people that we work with do not have capacity to understand and adhere to recommendations. Service Users depend on the staff team to ensure they are as safe as possible; following mealtime recommendations is part of this.

In working with staff teams on dysphagia cases, several relational themes are commonly seen:

Competent but reliant

The staff team are aware of the risks, understand and carry out the recommendations but are often very reliant on the speech therapist, unable to generalise the recommendations to different mealtime settings or less commonly encountered foods. For example ‘I know he can have mashed potato but do you think he will be ok on mashed swede?’

Caring but unaware

The staff team truly care for and have the best interests of the person at heart but they are unaware of the risks that eating certain foods would pose for a particular individual. For example they might say ‘well, he likes hard boiled sweets so why shouldn’t he have them’ despite incidents of the person choking on similar textured foods such as nuts.

‘Well rounded’

The staff team are aware of the risks and the recommendations and are able to employ a ‘common sense’ approach. For example ‘He has trouble chewing but he really wants fish and chips – lets make sure the food is cut up well and soften it with sauce’.

Elly brought several cases to the CAT supervision group, all related to dysphagia guidelines and working with staff teams. From discussions in the CAT supervision group and by applying CAT principles to other dysphagia cases, Elly began to identify 3 typically emerging relational patterns. The following are vignettes’ of cases that Elly took to the supervision group. Each of the cases described falls into one of the patterns identified.

How Julie and Elly had similar views of one particular group home

Both of us had worked in the same home and had similar frustrating experiences and this case followed the same pattern, with the same client. We describe what happened prior to either of us having the use of CAT’s relational tools.

About 12 years ago, Julie had received a referral for a man ‘Chris’ (a pseudonym), with profound learning disabilities (whose developmental level would be measured in months rather than years, if such measurement has any meaning) who uses a wheel chair. The staff team referred Chris to us as they wanted advice as to how to stop him masturbating continuously. Observations using momentary time sampling to arrive at a functional analysis showed how empty of alternatives his life was. However, although he rejected most attempts at interaction from other people, a careful analysis of his sensory awareness showed that he would respond to certain tactile stimuli, which he could access via staff helping to put in his hands certain toys. Despite further momentary time sampling clearly demonstrating a positive change in his behaviour when he was given the right stimuli, (and staff were encouraged to wash his hands before supporting him to experience these toys), staff continued to avoid him and to ignore the guidelines the psychologist developed. Julie tried hard and would revise her guidelines to see if staff would get to like them, but eventually gave up, feeling very disgruntled about what she saw as hopeless.

Approximately two years ago Elly was involved in working with the same service user. He was referred by a physiotherapist who had concerns about his safety at mealtimes. Assessment revealed limited chewing and a weak cough putting him at high risk of aspiration and asphyxiation. He was on a non modified diet, eating things such as chicken nuggets and crunchy chips and he was coughing with each mouthful.

A mashed diet was recommended based on observation of Chris eating a variety of textures. Staff were not happy to offer this as they felt that it negatively impacted on his way of life. Elly reluctantly agreed to trial a soft texture diet as this was safer than no modifications at all. Again staff raised concerns and Elly tried to compromise but staff felt anything other than access to a full textured diet would be unfair. After many revisions to the recommendations, hours of supervision and discussions with care management Chris was eventually discharged from speech and language therapy. He remains at risk of choking and suffers regular chest infections.

So when a referral came through for someone else in this home, we were starting this work of using CAT from the same reciprocal role position. Our position encouraged our mutual empathy for how awful this home was and our bonding about how we disliked working with them, because we saw clients there failing to benefit from our input. We were both aware of our negative feelings about the staff team’s attitude and these difficult experiences had stayed with us making us feel uncomfortable. On receipt of the latest referral we knew that both of us had one ‘voice’ saying to ourselves, “There’s no point going in there yet again“. The referral had come from a manager, not from the support workers themselves which meant we felt distanced and excluded from the team and how they felt ‘done to’ by us. However, we both were also saying to ourselves that we didn’t want it to be like this and we wanted to approach the work with a more open-minded attitude. We could both see the value of CAT’s relational mapping to help us see how we played into the prevailing attitude and how we could be more relational.

‘Adam’ was referred by his G.P at the request of home staff following two choking episodes (one requiring emergency services), from the same house as Chris. Elly assessed Adam and recommended avoidance of specific food textures and staff support with mealtime behaviours.

Several members of the staff team who had been present when Adam had choked were very receptive to the assessment and the recommendations, some offering ideas of strategies that seemed to support him. However, others were less convinced, stating that each mealtime is different so it is impossible to employ strategies consistently.

Previously Elly would have tried to value all views and incorporate them into the management plan (in the role of trying to please everyone), often resulting in a convoluted plan that was difficult to follow. On this occasion using the principles of CAT, Elly commented on the difference of opinion and how it was difficult to form a consistent picture of Adam with differing perspectives being offered. Elly suggested that she would make recommendations based on the assessment and that it would be the responsibility of the staff team to decide how to employ these practically.

Elly offered to facilitate a meeting to agree on how recommendations would be implemented but the staff team declined. However in a subsequent review visit it was noted that the recommendations made by Elly were actually being adhered to.

The difference with this and with previous experience with the home is that Elly took a more assertive role, which led to quicker outcomes for Adam.

‘Bill’ was referred by his G.P at the request of his Home Manager. Elly assessed Bill and recommended a ‘fork mashable diet’. On making this recommendation Elly sat down with the home manager and a senior member of staff to describe what this was and what types of food would be safe for Bill. The home manager and staff member reported that the recommendations and rationales behind them made sense and that they would pass information on to the staff team.

Several weeks later Elly contacted the home to review Bill and was told that his mother had heard about the recommendations and was very angry as she felt that it was over the top and ‘taking things too far’. The home manager stated that she agreed with her.

Elly recognised that she felt as though parent and home had taken an ‘attacking role’ leaving her in the role of victim. She also felt rejected by the home manager who had appeared to agree with the original recommendations.

The home manager felt that the recommendations needed to be discussed at a ‘best interest’ meeting. Elly agreed to attend and asked if it was best, having never met or spoken to Bill’s family, for her to contact Bill’s mother first to discuss concerns raised. The home manager did not give a definitive answer stating “I will leave it up to you but I know that she is not a happy bunny”. In the end Elly waited for the meeting to discuss Bill’s case.

At the meeting it came to light that there had been some miscommunication and the recommendations suggested by Elly closely matched the practices that Bill’s mother had employed when he lived at home.

By bringing the case to the CAT supervision group and looking at the roles being played out, Elly was able to hypothesise that her feeling of being the ‘victim’ was reciprocated by the Home Manager who may have felt that both SaLT and mother were criticising practices within the home. By keeping the two parties separate and appearing to empathise with both, the home manager was able to deal with the situation.

Taking this relational overview was very beneficial from Elly’s perspective because it encouraged her to challenge her default position which would typically be to take the situation very personally and feel attacked and rubbished, resulting in a somewhat defensive and defeated response.

‘Diane’ (a pseudonym) had been well known to SaLT for several years. She is an elderly lady with a severe learning disability, supported by a staff team who have known her for many years and who care deeply about her.

The recent referral was for a review of her eating and drinking. She was already on pureed food and thickened fluids and there was little in the way of texture modification that could be offered. The next step would be for Diane to be PEG fed (tube inserted directly into the stomach). As Diane was not coughing at every mealtime, not suffering regular chest infections and clearly gaining pleasure from eating and drinking, tube feeding was not considered a viable option by home staff or Elly. The difficulty faced was that on the occasions that Diane did cough it was traumatic for both her and the people supporting her; her eyes would water, she would go red in the face and occasionally her lips would turn blue. Staff were torn between championing her quality of life (on the occasions when she ate without coughing and enjoyed her food) or focusing purely on her safety.

Elly facilitated a meeting with the staff team to discuss the different emotions at play when considering Diane’s mealtime needs. This was a novel way of working for Elly because although eating and drinking is often an emotive topic, she typically used to stick to the clinical facts.

During the meeting issues and feelings raised by the staff team were mapped out in a CAT style. The outcome was that the recommendations remained the same but the exercise was valuable in allowing all present a safe environment to voice their hopes and fears for Diane.

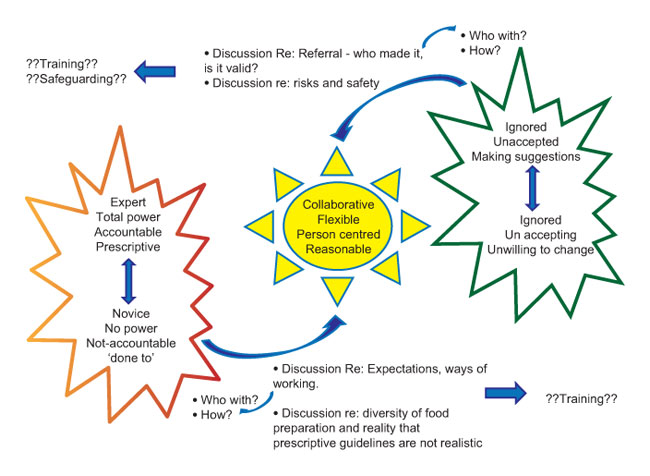

The map below illustrates the three commonly occurring relation patterns that Elly identified:

The central position describes Diane’s case and aims to describe a working relationship between SaLT and staff team where work is completed in partnership and the knowledge and skills of therapist and staff team are taken into account. All involved in the provision of care take some responsibility for managing risks and promoting quality of life.

The position on the left hand side shows staff teams who assume the position of handing all of the responsibility and risk management over to the Therapist and present as ‘helpless’. A typical comment made by staff teams in this position would be “you are the professional, we have to do what you say”. This is the pattern that can be best used to describe the relation pattern seen in Bill’s case

The position on the right hand side shows relationships where staff teams tend not to acknowledge risks highlighted by the therapist and who continue as they always have. This is similar to the pattern seen in Adam’s case.

From a SaLT perspective Elly has found using this map and the principles of CAT to consider the relationship between the Therapist and Staff team very useful for identifying why some cases feel more challenging than others when the clinical decision process is relatively straightforward.

In the past Elly would have arranged meetings and training sessions about the clinical difficulties but may not have acknowledged the complex relational issues between the therapist and staff teams or even within staff teams. CAT has been invaluable for highlighting that by identifying difficult relational patterns and addressing these, working relationships can feel much more productive and straightforward.

Because we sketched out this map in the supervision group, this map captured more than the situation in dysphagia work. We all identified with it (indeed we had all contributed to its creation) as it drew out typical relational problems when we, as health professionals, are asked to come in and fix a problem that is presented as beyond the staff team.

Elly Colomb is a Speech and Language Therapist is a Community Learning Disability Team. Julie Lloyd is a Clinical Psychologist and CAT Supervisor in the same team. As Elly is now on maternity leave, please send any comments to Julie.Lloyd@sabp.nhs.uk

References

Baker V, Oldnall L, Birkett E, McCluskey G and Morris J. (2010) Adults with learning disabilities (ALD). Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists Position Paper. RCSLT: London

*Carle, E. (1969). The Very Hungry Caterpillar. World Publishing Company.

Hardy S, Woodward P, Woolard P, Tait T (2007 revised) Meeting the health needs of people with learning disabilities RCN guidance for nursing staff. Royal College of Nursing: London

Full Reference

Colomb, E. and Lloyd, J., 2012. Cognitive Analytic Therapy & Dysphagia: using CAT relational mapping when teams can’t swallow our recommendations. Reformulation, Winter, pp.24-27.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Trauma, Trauma and More Trauma: CAT and Trauma in Learning Disability

Julie Lloyd, 2019. Trauma, Trauma and More Trauma: CAT and Trauma in Learning Disability. Reformulation, Summer, pp.44-46.

COVID Reformulation Postcards Katie Redman

Katie Redman, 2020. COVID Reformulation Postcards Katie Redman. Reformulation, Summer, p.10.

The Launch of a new Special Interest Group

Jenaway, Dr A., Sachar, A. and Mangwana, S., 2011. The Launch of a new Special Interest Group. Reformulation, Winter, p.57.

CAT Skills Training in Mental Health Settings

Freshwater, K. and Kerr, I., 2006. CAT Skills Training in Mental Health Settings. Reformulation, Summer, pp.17-18.

Psycho-Social Checklist

-, 2004. Psycho-Social Checklist. Reformulation, Autumn, p.28.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

A letter to the NHS...

Anonymous, 2012. A letter to the NHS.... Reformulation, Winter, pp.20-21.

Aims and Scope of Reformulation

Lloyd, J. and Pollard, R., 2012. Aims and Scope of Reformulation. Reformulation, Winter, p.45.

Anonymous Letters

Anonymous, 2012. Anonymous Letters. Reformulation, Winter, pp.22-23.

Book Review: Post Existentialism and the Psychological Therapies: Towards a therapy without foundations

Pollard, R., 2012. Book Review: Post Existentialism and the Psychological Therapies: Towards a therapy without foundations. Reformulation, Winter, p.43.

CAT in the NHS: Changes as a result of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the future of CAT

Vesey, R., 2012. CAT in the NHS: Changes as a result of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and the future of CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

Cognitive Analytic Therapy & Dysphagia: using CAT relational mapping when teams can’t swallow our recommendations

Colomb, E. and Lloyd, J., 2012. Cognitive Analytic Therapy & Dysphagia: using CAT relational mapping when teams can’t swallow our recommendations. Reformulation, Winter, pp.24-27.

Concerning the Future of CAT and Other Relational Therapies

Dunn, M. and Dunn, S., 2012. Concerning the Future of CAT and Other Relational Therapies. Reformulation, Winter, pp.10-13.

Editorial

Lloyd, J. and Pollard, R., 2012. Editorial. Reformulation, Winter, pp.3-4.

Exploring whether the 6 Part Story Method is a valuable tool to identify victims of bullying in people with Down’s Syndrome

Pettit, A., 2012. Exploring whether the 6 Part Story Method is a valuable tool to identify victims of bullying in people with Down’s Syndrome. Reformulation, Winter, pp.28-34.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Hepple, J., 2012. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Winter, p.5.

Past Hurts and Therapeutic Talent

Williams, B., 2012. Past Hurts and Therapeutic Talent. Reformulation, Winter, pp.39-42.

Reciprocal roles within the NHS

Welch, L., 2012. Reciprocal roles within the NHS. Reformulation, Winter, pp.14-18.

Relationships in Microcosm in Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Based on a workshop given at the 2012 ACAT Conference in Manchester

Hepple, J., 2012. Relationships in Microcosm in Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Based on a workshop given at the 2012 ACAT Conference in Manchester. Reformulation, Winter, pp.35-38.

The 16 + 1 interview

Wilde McCormick, L., 2012. The 16 + 1 interview. Reformulation, Winter, p.44.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.