A Sign for the Therapeutic Relationship

Akande, R., 2007. A Sign for the Therapeutic Relationship. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-7.

(Please note. Symbols used below have been substitued for the actual symbols use in the article. Please refer to the issue of Reformulation for the correct symbols.)

When some clients experience themselves as the focus of another’s attention, they feel intruded upon. Even the therapist’s attempts to be objective and descriptive rather than critical and blaming may be perceived as a form of threat. I had been quite accustomed to drawing an observing eye in the corner of client’s diagrams and explaining how this symbolised the process of recognition and self-reflection. One particular client, who found being the focus of therapy extremely disconcerting was even more distressed by the addition of the observing eye. She did not like looking at herself, let alone being “studied” by her therapist. However, it felt really important to find a way to represent the

therapeutic process conveyed by this sign; the client would need to see and understand her TPP before she could possibly change it.

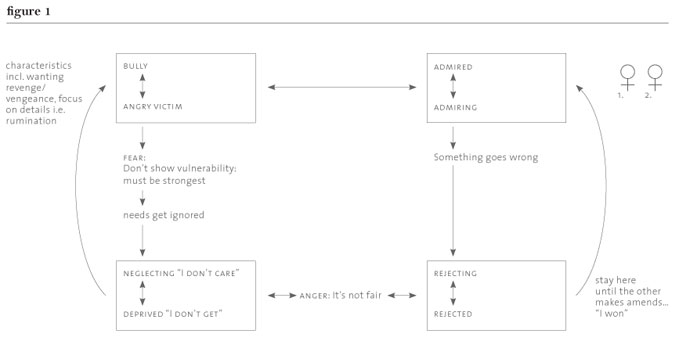

Jellema (2006) suggests that attachment theory can be useful in considering the client’s way of relating to others and the needs of the individual to form attachments. She suggested that work with very disturbed and traumatised clients makes this an invaluable consideration. Indeed, one of the reasons that I was drawn to CAT as a trainee clinical psychologist was its emphasis on relationship. Clients may perceive us as threatening, critical, or rescuers. Whilst we try to acknowledge this in our reformulation letters or by admitting where we find ourselves on the SDR, it seemed that there was a need for a more explicit sign of these processes. Hepple (2006) pointed to the importance of witnessing the client’s narrative, suggesting that the therapist is “beside the client … ”. I wanted to symbolize these thoughts whilst the client took that painful step into self reflection. And so, ♀ ♀ was born. Of course, if I am working with a male client, I would draw ♂ ♀.

I now use this image on all diagrams instead of the reflecting eye. I begin by drawing 2 ♀ on separate post-it notes. I stick them on a space away from the main TPP to emphasise the aim of therapy: “that we can stand back from how you usually find yourself relating to others and see the whole pattern”. Bakhtin comments that individuals have different perspectives (1990, in Hepple, 2006). This notion is clearly illustrated by showing that the two figures have slightly different view points. For example, in the diagram below, figure 1 obscures figure 2’s view of all the RRPs except Rejecting – Rejected. I emphasise that our aim is to recognise and understand each others perspectives without “brow-beating” each other into submission by stating that there may be things that we disagree on and our task is to be respectful and supportive to each other whilst sometimes needing to embrace those differences.

In figure one, the two figures are standing close together.

This proximity can demonstrate the strength of the therapeutic

relationship. As the images are drawn on separate post-it notes, they can also be moved around. Whilst it sometimes feels as though we are both reflecting, it can also feel as though we are not particularly united. I might represent this by moving one of the figures to the other side of the diagram:

Hepple 2006 also points out that the therapist’s identification with client’s reciprocal roles can draw him/her into enacting the

problematic procedures. The images can be moved around the SDR as might happen within the therapeutic relationship. For example, if the ending process evoked feelings of deprivation, as though the therapist did not care about the client’s needs, I might move images as follows:

I worked with one client who was denied a childhood and was involved in household chores from the earliest of ages. One of the goals of therapy was “to be able to have fun”. We made a game out of spotting enactments by moving our stick images from the reflective space onto the RRP, just like a child may use a doll to express his/her own feelings. In this way the images can be a tool to facilitate recognition and to rehearse exits.

CAT draws together several different psychotherapeutic theories. Pollard (2002) points out that these theories offer different definitions of the self. Further, therapeutic orientation may influence one’s understanding of how the self developed. Nonetheless, most clients can understand and envisage a process whereby roles may be parent- or child-derived. I often suggest that we need to evoke that inner child and listen to what s/he is still struggling with. Most clients believe that they do have an inner child. However, many also have difficulty listening to that

inner child, and the stick images can be used to help identify internal (“self – self ”) dialogues. For example, X had an intense sense of loneliness. He also had a critical – disappointing RRP. A great deal of his therapy focussed on how he might fail me and be a “bad client”. Eventually, he was able to acknowledge that his prediction that I would be disappointed was his own internal dialogue: he was being critical of his own achievements in therapy and felt disappointed with himself. He was then able to see the similarity between how he thought about himself (his inner adult dialogue) and how his parents had treated him in childhood. This led him to access memories of how he felt as a child when his parents were critical of him (his inner child dialogue).

Ultimately, the client chose not to accept his parent-derived view of himself and to listen to his inner-child who, once encouraged to speak, was highly motivated to socialise with other people. In his goodbye letter, X talked of how the intense sense of loneliness was carried by his inner-child. Once he had listened to his inner child and felt more connected to him, the whole self was then ready to be connected to the outside world.

In the past, I had been encouraged to write up my use of these stick images, but was not sure whether any one else would find such an article particularly interesting. It was not until I read Irene Elia’s article on “the inner voice check” (Reformulation, Issue 28) that I was enthused into writing this article. I was struck by how useful the child-parent images could be. Certainly, if they were used in conjunction with stick people, they could offer a creative way of incorporating a developmental and current relating perspective onto SDRs. I would be interested in other

people’s comments or adaptations to the use of these images.

Rachel Akande rachel-s.akande@pr-tr.wales.nhs.uk

References

Elia, I. 2007. The Inner Voice Check. Reformulation, 28. pp 28-29.

Hepple, J. 2006. The Witness and the Judge: Cognitive Analytic Therapy in later life: The case of Maureen. The British Journal of

Psychotherapy Integration: 2 (2); 21 – 27. ACAT reference library.

Jellema, A. 2006. An Animal Living in a World of Symbols. ACAT reference library.

Pollard, R. 2002. What do we mean by the Self in CAT? Implications for Research. ACAT reference library.

Full Reference

Akande, R., 2007. A Sign for the Therapeutic Relationship. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-7.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

The Inner Voice Check

Elia, I., 2007. The Inner Voice Check. Reformulation, Summer, pp.28-29.

Letter from the Editors

Elia, I., Jenaway, A., 2007. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Winter, p.3.

Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities

Frain, H., 2011. Working within the Zone of Proximal Development: Reflections of a developing CAT practitioner in learning disabilities. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-9.

Developing a Language for the Psychotherapy of Later Life

Hepple, J., 2006. Developing a Language for the Psychotherapy of Later Life. Reformulation, Winter, pp.23-28.

Using The Parent-Adult-Child Model Alongside CAT

Louise Elwell, 2017. Using The Parent-Adult-Child Model Alongside CAT. Reformulation, Winter, p.43.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

A Sign for the Therapeutic Relationship

Akande, R., 2007. A Sign for the Therapeutic Relationship. Reformulation, Winter, pp.6-7.

Cuckoo Lane

Elia, I., 2007. Cuckoo Lane. Reformulation, Winter, pp.4-5.

Evidence submitted by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (NICE 92)

Rowland, N., 2007. Evidence submitted by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (NICE 92). Reformulation, Winter, p.20.

In the Beginning was the Conversation 'Process' Spirituality and CAT

Dunn, M., 2007. In the Beginning was the Conversation 'Process' Spirituality and CAT. Reformulation, Winter, pp.16-19.

Letter from the Editors

Elia, I., Jenaway, A., 2007. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Winter, p.3.

States Characterisation Procedure (SCP) for supporting the reformulation of patients with borderline/dissociative features

Ryle, A., 2007. States Characterisation Procedure (SCP) for supporting the reformulation of patients with borderline/dissociative features. Reformulation, Winter, pp.9-11.

Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy with parents: some theory and a case report

Jenaway, A., 2007. Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy with parents: some theory and a case report. Reformulation, Winter, pp.12-15.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.