Integration of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Understandings

Ruppert, M., Birchnall, Z., Bruton, C., Christianson, S., 2008. Integration of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Understandings. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-22.

Introduction

The Study was completed as part of a top-up doctorate programme. The workshop presenters were: Maggy Ruppert, Steve Christianson, Zoe Birchnall and Carol Bruton. Zoe and Carol facilitated the experiential groups at the workshop as well as the CAT Group.

Rationale for the Study

The words of Ryle and Kerr (2003) have provided a rationale for going in this direction:

‘The extent to which CAT theory and practice as used in this (a group) setting has been genuinely integrated with the theoretical framework of group psychotherapy, of whatever theoretical orientation, has, however, been much more limited. There are clearly conceptual overlaps between these approaches, notably the interest in and therapeutic focus on the individual as a social being. Nonetheless, as is well recognized, complex transpersonal processes are enacted within groups to which the understandings of the CAT model have not yet been rigorously applied and this remains an area of potential exploration. The overlapping and complementary paradigms of CAT and group psychotherapy could certainly benefit from such work…’

Previous published studies and accounts, such as Duignan & Mitzman (1994) and Maple &Simpson (1995) describe groups that typically begin with participants who have experienced either a full CAT or the initial four sessions including sequential diagrammatic reformulations (SDRs) and sometimes reformulation letters as well. This way of doing group therapy creates a lot of work outside of the group, and we wondered if this has deterred clinicians from this way of working? We also question if the individual CAT work before the group may encourage greater dependency on the group therapists/facilitators and impede the group participants’ working with each other. Given that our aim was to provide an interactionally orientated group that used CAT understandings and tools to facilitate the group work, rather than doing CAT in a group, we chose not to do any individual CAT work prior to the group.

CAT and Group Therapy – the Natural Point of Integration

The groups we are familiar with running draw heavily on the idea that the group is a social microcosm. Yalom describes the group as being like a laboratory:

‘…. sooner or later the participants will begin to interact much as they do in any group, they replicate their relationship patterns within the group. Thus, the facilitators need not know anything about the participants before they begin the group…’

A primary role of the facilitators then is in enabling participants to work in the ‘here and now’ (Yalom 1985). They encourage participants to observe, explore, and reflect on their interactions within the group. This is not so different from what occurs with CAT, but the advantage of a group is more opportunities for patterns to be enacted. Furthermore, with two facilitators and participants empowered to notice their own and others’ reciprocal roles and procedures through the use of CAT tools, there is ample opportunity for recognition and revision and less risk of un-noticed entrapment and collusion. In this study the live supervision via a camera link further increased the potential to observe, understand, and articulate the patterns in a helpful way.

What we did – the How, What, Where and Who

Environment

We had a group room with two discrete cameras in the top opposite corners which provided live feedback to a room across the corridor where Maggy and Steve were observing. The SDRs were displayed on A5 sheets on a large Board, and each participant had an A5 diagram facing them on the floor in front of their seats. They also received a copy of their own and each others’ diagrams for reference outside of the group.

Preparation

This model of therapy, utilising the social microcosm, does not require the group facilitators (Zoe and Carol) to know the participants before they enter the group.

Following referral, Maggy saw each participant for a single session of 45 –60 minutes duration. This was to meet Ethics Protocols and to prepare people for the group. All participants were given details of the research and consent forms prior to the appointment as well as our usual group therapy hand-out with minor modifications. The session was to ensure the criteria for inclusion were met and to prepare participants for the group. Thus during this meeting Maggy explained briefly the basics of reciprocal roles and procedures and drew an exemplar diagram for each person to aid explanation of how these would be used in the group. The client also completed a CORE-OM.

Participants

Seven people were referred, 3 men and 4 women. One male dropped out before assessment was completed due to the impracticality of attending, and one female was asked to leave after missing sessions 3 and 4 and informing us she could not come to session 5. She was offered an alternative group.

The 5 remaining participants will be known as: Bea, Dee, Sue, Ian and Rob.

CORE (O-M) scores ranged from 1.87 to 2.93

(The range for a clinical population is 1.31-2.93 (Evans et al, 1998)).

All four attendees were referred to the group from within secondary mental health care, except Sue who had previously attended our Emotional Regulation Group and was recruited

from there.

Biographies

Bea – a woman in her 50s, single but with a partner. Nurse by background, currently not working due to mental health problems that had been with her on and off over many years. She had recently relocated to the UK from abroad and was referred to the service ostensibly with depression.

Dee – a woman in her early 30s with two primary aged children. Her partner died in a traffic accident two years prior. She was currently in a volatile relationship and she announced during the group that she was expecting their child. (She gave birth two months after the follow-up group.) Referred to service from A&E following an overdose.

Sue – a woman in her mid 30s, single and socially isolated. She dropped out of school aged 13. Relocated moved to this area having completed a two year intensive individual psychotherapy in another part of the country, which was provided after a very serious significant suicide attempt. Currently on an Access course.

Ian –in his 20s, living with his partner but uncomfortable about how others viewed his relationship which was same sex. He worked full-time in a responsible job but suffered severe anxiety and suicidal feelings. And described a rather overprotective mother.

Rob – in his late 30s, a househusband with two primary school aged children. Referred for mood difficulties but in a very difficult long-term relationship. On referral identified difficulty in relating to others. He had spent much of his early years in a children’s home after his father died. Although adopted at 12 he was subsequently boarded at school and since adulthood has been estranged from his adoptive parents.

All participants had abandonment issues and all but Ian describe harsh, critical, neglecting, and emotionally deprived childhoods, some with abuse.

The Group Session Structure and Time

16 weekly sessions with a follow-up 11 weeks after. (There was also a focus group with the researcher, 2 weeks after this, in order to gain feedback for qualitative analysis).

The group ran for 90 minutes. Fifteen minutes before the end, the facilitators would stop the group and spend 5 to 8 minutes discussing, in view of the participants, how they experienced the group and their observations. After this chat, the facilitators would go round the room inviting each participant to share their comments on their experience in the group that day as well as responding to the discussion of the facilitators if they so wished. It was customary to comment on how they were feeling. This is based on Yalom’s work and something we use in other groups. It was not specific to the CAT group but is consistent with the summing up and review that is good practice within CAT sessions.

Outcome

SDRs were done in the group. We had anticipated this would take 3-4 sessions. In fact they were completed by session 2. An example is provided below; there was a necessity to keep them simple in order to be useable.

A Group Reformulation Letter was prepared for session 4 though in fact it was presented at session 5. Diagrams were referred to throughout and more active encouragement to write in Exits were made by the facilitators around session 12.

All Participants attended Session 16. A group Goodbye Letter was read out by the facilitators. Three group participants brought and read out their letters. The other two described efforts to do a letter but were unable to bring them.

Attendance

75 out of a total of 85 sessions were attended. Five absences were unplanned.

Measures

The study was primarily qualitative and data is still being analysed. All participants attended the focus group. In addition all were invited to complete two forms after each group session and send them to a secretary for analysis after the therapy had concluded. One participant completed zero post-group session feedback forms, the remaining 4 completed on average about 8 of a possible 17 each.

Process and Feedback on Outcome

The group process and commentary on what occurred in the group, including participants’ letters and our letters to the group, is probably of most interest but would exceed the remit for this article. There was high enthusiasm from the facilitators and supervisors for the group, and we have plans to run another one. Our subjective impression was that the group was able to reach where individual therapy cannot. We felt the CAT tools enhanced the pace of the group and we felt the participants probably gained more from this group in the time than a comparable interactional style group. We were left invigorated rather than exhausted which perhaps speaks volumes for the impact that the participants and this way of working had upon us.

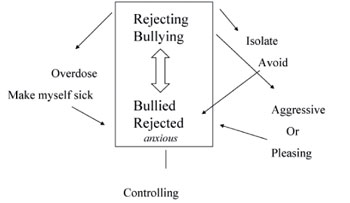

For us the CAT tools of the diagram enabled us to feel contained and to be active very quickly with the core issues that the participants were struggling with. For example in Session 3, when Sue was clearly troubled but not wanting to verbalise what she was feeling, Zoe went to her diagram (illustrated in this article) and named the dilemma she had as a facilitator: ‘…I want to respect what you are saying – you say ‘give me 10 minutes’ but I am aware that you may be in your pattern of isolating and avoiding?’ This was enough to enable Sue to say what she needed to.

Participants were generally positive about the group. They valued the reformulation letter mainly because it helped them to know that they had been heard and the facilitators were attentive. We feel it also encouraged the culture of working actively with each other on patterns. They found the ending difficult and wanted the group to continue in one form or another. They expressed the range of responses we are familiar with in individual CATs, such as disappointment and fear as well as appreciation and hope. One participant in the group commented that she felt that they had been ‘cherry picked’ for the group, such was the level of cohesion and understanding between members. However, this was balanced by another person commenting that she thought the researcher would have had anyone in the group!

This discussion reflected the level of cohesion and sense of belonging achieved within the group, and given the struggle each member had with social isolation it seems likely that some corrective emotional experience was achieved through the felt sense of belonging within the group. The fact that each participants’ reciprocal role pattern reflected their struggle in one way or another, with belonging-- be it with rejection, abandonment, ignoring or neglecting patterns --it was heartening and indeed inspirational for us to see how they worked with each others’ patterns and gently challenged (well actually not always gently! ) each other. At the same time, they gained recognition and feedback on their own contributions. In this process they experienced a sense of acceptance and value from their peers. For us the issue of belonging would be singled out as being the hardest to address within an individual psychotherapy, and yet it is pivotal to improved well being.

Another core feature of this style of group therapy is that it allows and enables participants to become more aware of what they have to offer, and in offering to others they offer to themselves. Thus the choice of the term of facilitator rather than therapist is deliberate; our role is to enable participants to heal each other and themselves and in so doing rediscover their value and self worth. All participants had considered and some had made serious attempts to take their own life prior to the group. Therefore, with this in mind, we end this submission with the final paragraph of one participant’s goodbye letter:

‘…’This group experience has been good for me – a unique experience that will stay with me. We should all be proud that we stuck it out to the end. Hopefully we have all learned that we need to love ourselves a little bit more and to value our precious lives.’

References

Duignan, I.A. & Mitzman, S. (1994) Measuring individual change in patients receiving time-limited cognitive analytic group therapy. International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy, 9, 151-160.

Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Mellor-Clark, J., Margison, F., McGrath, G., & Audin, K. (1998) CORE System Information Management Handbook

Maple, N., & Simpson, I. (1995) CAT in groups

in Ryle, A. (Ed.) Cognitive Analytic Therapy 77-101 Wiley

Ryle, A. & Kerr, I. B. (2003) Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy. p 174 Wiley

Yalom. I. D. (1985) The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy

3rd Edn Wiley

Authors

Email any of us using our names

e.g. Maggy.Ruppert followed by @nwmhp.nhs.uk

We are based in Norwich working for the City Locality:

Maggy Ruppert Consultant Clinical Psychologist ACAT Practitioner and Accredited CAT supervisor.

Zoe Birchnall Nurse Therapist, Integrative Therapist, CAT aware BAC registered .

Carol Bruton Nurse Therapist CAT Diploma and Practitioner, BAC registered.

Steve Christianson Nurse Therapist CAT Diploma

Maggy, Steve and Zoe have been running interactive Yalom style groups continuously for the last 13 years and are regular contributors to the group skills training for the clinical psychology doctorate programme at the University of East Anglia. Carol has been running groups for the last 3 years alongside her CAT work.

Full Reference

Ruppert, M., Birchnall, Z., Bruton, C., Christianson, S., 2008. Integration of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Understandings. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-22.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Effectiveness of Group Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) for Severe Mental Illness

Dr Laura Brummer & Olivia Partridge, 2019. Effectiveness of Group Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) for Severe Mental Illness. Reformulation, Summer, pp.29-31.

International ACAT Conference “What Constitutes a CAT Group Experience?â€

Anderson, N., M., 2009. International ACAT Conference “What Constitutes a CAT Group Experience?â€. Reformulation, Winter, pp.25-26.

Reflections on Our Experience of Running a Brief 10-Week Cognitive Analytic Therapy Group

John, Dr C., Darongkamas, J., 2009. Reflections on Our Experience of Running a Brief 10-Week Cognitive Analytic Therapy Group. Reformulation, Summer, pp.15-19.

CAT Reflective Practice Groups

Jason Hepple, 2018. CAT Reflective Practice Groups. Reformulation, Winter, pp.22-25.

Capturing Service Users’ Views of Their Experiences of Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT): A Pilot Evaluation of a Questionnaire

Phyllis Annesley and Alex Barrow, 2018. Capturing Service Users’ Views of Their Experiences of Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT): A Pilot Evaluation of a Questionnaire. Reformulation, Winter, pp.14-21.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually

Murphy, N., 2008. CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually. Reformulation, Summer, pp.26-30.

Catch up with CAT

Potter, S., Curran, A., 2008. Catch up with CAT. Reformulation, Summer, p.54.

Clinical Implications for the Pregnant CAT Therapist

Knight, A., 2008. Clinical Implications for the Pregnant CAT Therapist. Reformulation, Summer, pp.38-41.

Consent to Publish in Reformulation

Jenaway, A., Lloyd, J., 2008. Consent to Publish in Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, p.7.

Cuckoo Lane

Selix, M., 2008. Cuckoo Lane. Reformulation, Summer, p.6.

How to Enjoy Writing a Prose Reformulation

Wilde McCormick, E., 2008. How to Enjoy Writing a Prose Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, pp.16-17.

Integration of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Understandings

Ruppert, M., Birchnall, Z., Bruton, C., Christianson, S., 2008. Integration of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Understandings. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-22.

Is CAT an Island or Solar System?

Bancroft, A., Collins, S., Crowley, V., Harding, C., Kim, Y., Lloyd, J., Murphy, N., 2008. Is CAT an Island or Solar System?. Reformulation, Summer, pp.23-25.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Westacott, M., 2008. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.3-4.

Letter from the Editors

Elia, I., Jenaway, A., 2008. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Summer, p.3.

Metaprocedures in Normal Development and in Therapy

Hayward, M., McCurrie, C., 2008. Metaprocedures in Normal Development and in Therapy. Reformulation, Summer, pp.42-45.

Plugging in and Letting Go: the Use of Art in CAT

Hughes, R., 2008. Plugging in and Letting Go: the Use of Art in CAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.9-10.

Service Innovation

Jenaway, A., Mortlock, D., 2008. Service Innovation. Reformulation, Summer, pp.31-32.

Silence in Practice

Harvey, L., 2008. Silence in Practice. Reformulation, Summer, pp.11-13.

The ‘Human Givens’ Fast Trauma and Phobia Cure

Jenaway, A., 2008. The ‘Human Givens’ Fast Trauma and Phobia Cure. Reformulation, Summer, pp.14-15.

The Body in Dialogue

Burns-Lundgren, E., Walker, M., 2008. The Body in Dialogue. Reformulation, Summer, pp.18-19.

The Development of the Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation

Parkinson, R., 2008. The Development of the Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, pp.33-37.

The States Description Procedure

Hubbuck, J., 2008. The States Description Procedure. Reformulation, Summer, pp.46-53.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.