CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually

Murphy, N., 2008. CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually. Reformulation, Summer, pp.26-30.

for a client with Learning Disability and Asperger Syndrome

Introduction

Although there has been some literature on the application of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Hare, 1997 and Reaven & Hepburn, 2003) and psychoanalytic therapy (Jacobsen, 2004) to people with Asperger Syndrome (AS), to my knowledge, there is no literature on the use of Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) with people with AS.

In this paper I will attempt to summarise how CAT was implemented through individual therapy with a man with learning disabilities and AS. I will also show how the Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation (SDR) was used contextually with his staff team.

The Model: Cognitive Analytic Therapy

Anthony Ryle initially developed CAT in the late 1970’s. Since then it has been further developed. It is a time limited psychotherapy in which a letter of reformulation is written to the client, in order to explain how their early experience influenced the formation of unhelpful roles and procedures that maintain current difficulties. The purpose of therapy is to help clients recognise and revise these roles and procedures. A diagram (Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation) is created with the client, based on the reformulation letter; to further assist recognition and revision of roles and procedures.

The Case Example: Brief Summary

Referral

Max was referred by a Clinical Psychologist from his previous placement. She stated that he had had regular input from her since his admission to an inpatient unit one year prior to the referral. He had a “history of self-injurious behaviour, obsessive compulsive disorder, and had been diagnosed elsewhere with Asperger Syndrome”. She requested that he continue to receive psychological input on his resettlement to the local area.

The Client

Max was the eldest of three children. He had developmental delays and attended a residential school for children with learning disabilities from the age of five. He stayed with his parents every other weekend and in the school holidays. From the age of ten he attended a boarding school for children with behavioural problems. On leaving school he undertook courses at an agricultural college. He was admitted to an inpatient service at the age of twenty-seven following “aggressive outbursts at home involving damage to property, intimidating behaviour towards his mother and fighting with his brother”. Due to an increased risk to himself and others he was detained under the Mental Health Act. It was on his discharge a year later that he was resettled and the referral made.

Max had a mild learning disability. He could independently read and write. He had good sequencing ability and a good sense of time. He was able to verbalise his thoughts. He also expressed himself by writing his thoughts down. He had good understanding of the concepts used in CAT and was able to retain the sessions’ content.

The Context

Max lived in his own flat, which was part of a small block of flats where other clients also lived on their own. There was a staff flat too. All residents were allocated hours of support. In Max’s case this was to help him with tasks of daily living and to access community facilities. The staff flat had drop-in sessions for designated time periods in order to facilitate social networking between the residents. Since the flat was staffed 24 hours, staff could be accessed outside of the allocated hours when necessary.

Therapeutic Input: Assessment

Max and I met for a total of forty-six sessions. The first two sessions were initial assessment sessions. Presenting problems identified were:

1. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

OCD is an anxiety disorder characterised by intrusive thoughts, images or worries (i.e. obsessions) and/or repetitive, non-functional behaviours (i.e. compulsions) that emerge in an effort to quell anxiety (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Symptoms are time consuming, cause considerable functional impairment, and often contribute to increased social isolation, persistent distress, and a progressive narrowing of behaviour and interests (Reaven & Hepburn, 2003). OCD may occur more frequently in those with AS (Kerbeshian and Burb, 1986).

Max informed me that for many years he had a compulsion to wash and that this was based on a fear of being dirty and getting germs. He would then worry that either he would become ill or that he would pass the germs on to others and cause them serious harm. There had been episodes where he had spent periods of up to four hours in the bath continuously washing due to thoughts of being contaminated with germs.

In individuals with AS it is difficult to ascertain what are stereotyped behaviours associated with AS and what are behaviours associated with OCD. Reaven & Hepburn (2003) differentiate some of the obsessions that are associated with the autistic spectrum as opposed to OCD and state that adults with OCD are more likely to engage in cleaning, checking and counting behaviour. In contrast, adults with AS are more likely to exhibit repetitive ordering, hoarding, telling/asking and repeated touching. As stated previously Max engaged in lengthy cleaning rituals. These interfered with his daily activities and he became distressed if anyone tried to prevent him from engaging in the behaviour. Thus, it appeared that these were linked to OCD, rather than his AS.

1. Self-Harm

Max pulled the skin off the bottom of his feet. This often caused bleeding and required his feet to be wrapped in bandages to aid his mobility. In the past he had hung himself upside down off the side of his bed and held his breath, which had resulted in bilateral conjunctival haemorrhages. He had also taken overdoses of prescribed medication resulting in hospital admissions.

I referred Max to an Occupational Therapist (OT) to undertake a sensory integration assessment to ascertain whether or not his self-injury was due to difficulties with processing sensory information. The OT concluded that it was difficult to isolate a specific sensory processing problem.

2. Asperger Syndrome

Max had formally received a diagnosis of AS. People with this disorder have impairments in social interaction, social communication, and imagination and social understanding. Aspects of the disorder relevant to the therapeutic input will be described in more detail later on.

3. Learning Disability

As mentioned earlier, Max had a mild learning disability. He was more ‘disabled’ by his Asperger Syndrome, rather than his learning disability.

4. Generalised Anxiety and Health Anxiety

Max presented as being highly anxious. Tantum (2000) states that high anxiety is a feature of many people with autistic spectrum disorders, especially when there is a family history of anxiety disorders. Max said that his mother presented as being highly anxious and would engage in obsessive rituals.

It transpired that when Max was anxious, he experienced somatic symptoms, which he interpreted as an indication that he was seriously ill. He then engaged in his washing rituals and self-harm behaviour in response to the anxiety that he was experiencing.

Max informed me that he ruminated about developing various life-limiting illnesses and disorders.

Intervention

Step One: Engagement

Nineteen sessions were spent doing life story work. During sessions, Max chose to write about important events in his life in a chronological order. The purpose of this was to get a sense of his early life and how this was affecting him. Also, as the previous psychologist had reported that Max had difficulties engaging in psychology sessions, the writing enabled him to tell me about significant events in his life through both verbal and written communication. This helped him to enjoy the sessions, as it was something he did not find threatening. Thus it also acted as a means of building a therapeutic relationship. The life story also provided a structure to the sessions, which reduced the frequency of Max asking questions and seeking reassurance.

Step Two: CAT Therapy

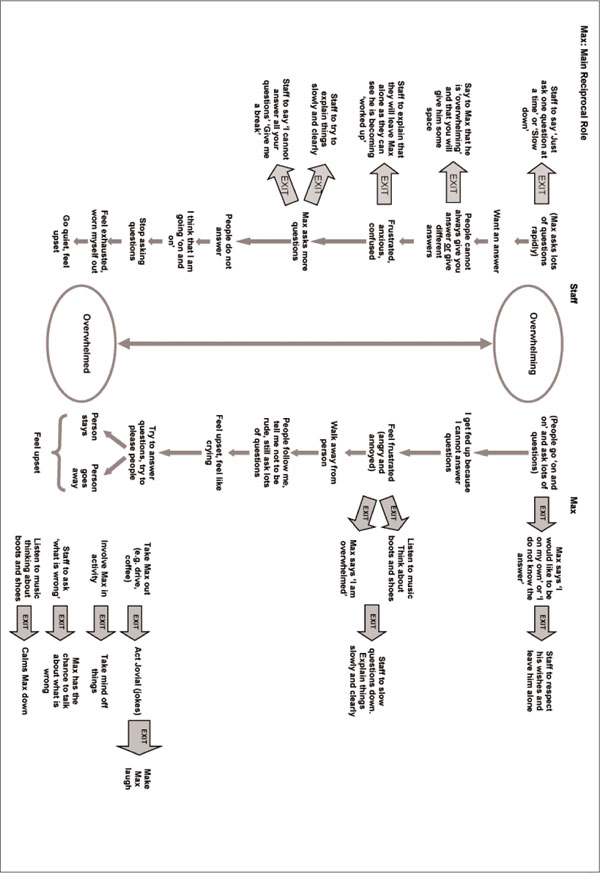

Max was then offered twenty-four sessions of CAT. I and others experienced Max as being very overwhelming, as he would ask a series of questions in quick succession and constantly seek reassurance. Due to his AS he experienced the world and others as very confusing and would frequently feel overwhelmed. Max and I therefore chose to work on one main reciprocal role of overwhelming to overwhelmed. Reciprocal roles are the way in which we relate to significant others that are based on early experiences. They are similar to analytic concepts of transference and counter transference. Although there were other reciprocal roles present we agreed that to work on several roles at once would be overwhelming!

Explanation of Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation (SDR: Appendix 1): Max’s Experience

Max experienced people asking him a lot of questions or giving him lots of information as overwhelming. When this occurred he became frustrated, as he could not always answer their questions. He told me that he walked away from the person, but that people often followed him and continued to ask him questions. He said that he felt upset and felt “like crying”. He said that he tried really hard to answer their questions and tried to please them. If the person stayed with him and continued to ask questions he found them overwhelming. If they left him he worried that he had offended or upset them. Either way he was left feeling upset and overwhelmed.

Others’ Experience

Others’ experienced Max as overwhelming, as he asked lots of questions in quick succession. Although he was seeking answers and reassurance, he often did not allow any time for the person to answer his questions, which would lead to further questions. Sometimes people were not able to give him answers, which made him feel frustrated. Or people gave different answers to the same question, which left him feeling anxious and confused. When he was feeling frustrated, anxious and confused he asked more questions. People did not always answer him, and he thought that he was going “on and on” and stopped asking questions. He felt exhausted and worn out which resulted in him going quiet and feeling upset. He felt overwhelmed.

‘Exits’

Enabling Max to challenge his dysfunctional beliefs about illness, contamination and germs proved to be difficult due to the rigidity of his thinking, as is often present in people with a diagnosis of AS.

To address his rigid thinking, what proved to be effective was Max having his ‘exits’ outlined to him in ‘black and white’. He could rote learn these and then apply them when he recognised he was in his ‘trap’. For example, when he thought he had “AIDS” he could think about the ways HIV was transmitted and that these did not apply to him.

In addition to this, staff had specific ‘exits’ that they could use if they felt Max was overwhelming them. We started off doing this in the confines of the therapeutic relationship. For example if Max was asking me multiple questions rapidly, I would ask him to him to “Slow down” and tell him how this helped me not to feel overwhelmed. Once Max could recognise my ‘exit’ in the therapy sessions, staff were then instructed to use the ‘exit’ also. Once the staff team used their ‘exits’ consistently, Max was able to generalise. When he felt more confident using his ‘exits’ and recognising others’ ‘exits’ within his core staff team, he then was able to generalise this to family members and other people who worked with him.

Step Three: Staff Support and Staff Training

For the duration of therapy I facilitated regular staff support groups. The purpose of these was for Max’s core group of staff to have a forum to discuss issues and generate strategies when working with him.

More formal staff training events then took place that involved all of his staff team. The purpose of these was to share the SDR. The staff team were encouraged to use their ‘exits’ when Max overwhelmed them, as this would help him recognise when he was being overwhelming. In addition, their using ‘exits’ with him would give Max more confidence to use his ‘exits’ with them.

The team were also informed what Max’s ‘exits’ were and were encouraged to respect these when he used them, for example to give him “time and space alone”. The more accepting and supportive the team were when Max used his ‘exits’ the more he used them. Initially Max feared that he would offend the staff team by using his ‘exits’, but the staff team respecting him when he used his ‘exits’ reduced the fear.

Thus, the diagram was used to enable the staff team to recognise the reciprocal role enactment and see the logical ‘exits’ both for them and Max. The ‘exits’ were then incorporated into Max’s care plan.

Characteristics of Aspergers Syndrome

and How CAT Addresses These:

Social Interaction

Max wanted to interact with others but was unsure how to and/or found it too anxiety provoking. At the beginning of therapy there was no reciprocity. Using the SDR we reflected on how his asking too many questions leaves him feeling frustrated, anxious, and confused. We therefore incorporated an ‘exit’ that would not only help to reduce these feelings but also help develop reciprocity. The ‘exit’ was for people to say, “Just ask one question at a time”. By initially doing this in the therapy sessions, Max learned that he got his question answered and that this reduced his difficult feelings. It also modelled turn taking and appropriate interaction.

The collaborative approach of CAT with the emphasis on the therapeutic relationship helped to serve as a model for other relationships and thus reduced his difficulties with social interaction.

Social Communication

Impairments in social communication identified were Max’s literal interpretation of language, his repetitive questioning, and his occasional incessant talk about his subject of interest, regardless of the response of others.

Due to his literal communicative style the rating sheet was difficult to complete in order to interpret and monitor change. Instead we compiled a list of his difficulties at the beginning of therapy and asked him whether or not he was still experiencing these difficulties at the end of therapy. By doing this Max was able to not only monitor change according to items on the list, but was also able to add areas of progress, such as now being able to undertake college courses, which had previously been too anxiety provoking. As with other people with AS, metaphorical concepts and language were avoided and a concrete approach was used.

The repetitive questioning and incessant talk on his subject of interest were understood in terms of the procedures within his SDR.

Imagination and Social Understanding

As with many people with AS, Max had difficulties imagining the future and hence experienced difficulties with planning and organising. His inability to imagine the future led to difficulties with change and heightened anxiety. The structured nature of CAT makes the therapy predictable. For instance the maintenance of boundaries was imperative to help Max feel safe and contained. These were not only ‘physical’ boundaries such as meeting at the same time each week in the same room, but also relational boundaries between therapist and client. Identifying a problematic procedure, such as being overwhelming by asking too many questions too quickly, also gives structure by identifying and agreeing a focus for intervention. The very nature of the SDR also gives a degree of structure via suggesting how to respond to others and predicting how they will respond in return.

Theory of Mind

Deficits in theory of mind mean that people with AS have difficulty explaining their own behaviour and understanding how it impacts on others. People with AS also have difficulty understanding others’ perspectives, inferring the intentions of others, understanding emotions, and predicting the emotional state of others.

The use of the SDR, however, gives a structured framework that clearly outlines the perspective of others. From this Max could develop an understanding of how he affected others. Understanding his own and others’ emotions in relation to behaviours (e.g. constant questioning) ensured that he could now sometimes predict the reactions of others to him.

Being explicit about my feelings in sessions also helped Max understand how he was affecting me. So, as stated previously, I would use an ‘exit’ such as “Slow down”, and then state how Max’s slowing down helped me to not feel overwhelmed. Over time Max was able to recognise for himself when he was talking or asking questions rapidly and ask, “Have I overwhelmed you?” At the end of therapy, one of the ways in which Max felt he had made progress was “thinking of others feelings”, demonstrating an improvement in this theory of mind task.

Progress

With regard to the presenting problems identified at referral and initial assessment, Max had made significant improvements in a number of areas by the end of therapy. There was a significant reduction in his self-harm and obsessive washing. This appeared to be due to a reduction in his anxiety levels. In addition, he was more assertive and engaged in activities that he had previously avoided.

Staff identified that he was using his ‘exits’ with them and also removing himself from situations that he found overwhelming and re-joining the group/activity when he felt able to. They stated that previously Max would not have been able to do this (for fear of offending others), which would have resulted in increased anxiety and associated difficulties (e.g. self harm). The staff also reported that Max was checking if he had misinterpreted situations, which enabled a discussion to take place, preventing potential difficulties. They stated that previously Max would have ruminated about events, culminating in increased anxiety and associated difficulties. It was only at this point that staff would have been aware of a problem.

Maintenance of Change

Since this episode of therapy four years ago, Max has been referred again twice. The first referral was fifteen months later. This was with respect to memories of being bullied at school and how this was affecting his interaction with his staff team. We met for four sessions and re-visited the diagram and ‘exits’. The goal was to understand his difficulties within the context of the SDR. He still had a good understanding of his SDR. Max was clearly still using his ‘exits’, as were the staff team with him. The further sessions enabled Max to build on his progress from the previous episode of psychological therapy.

Two years elapsed before Max was referred again. It was recognised both by him and the staff team that there was some re-enactment of reciprocal role procedures. Max appeared to be misinterpreting some of his interactions with staff, which was causing difficulties for him and the staff that supported him.

We met for four sessions. There had been a number of areas of noticeable maintenance of change. For example, in the initial session we re-visited the diagram and incorporated more ‘exits’, without Max displaying anxiety, repetitive questioning, or reassurance seeking. He was able to work quickly without either of us feeling overwhelmed. He had also continued to make improvements with regard to theory of mind and had much better sense of others’ perspectives and how he impacted on people. He was able to use terms of reference (e.g. worked up) in the right context and so had continued to make improvements in the area of social communication.

As the staff team had changed significantly from the initial therapeutic input four years earlier, two further staff training events took place. It appeared that some of the difficulties that had prompted this referral were due to a change in staff team and them not being fully aware of the previous work. This meant that they did not recognise when Max was using his ‘exits’, nor did they know what their appropriate ‘exits’ should be. Max’s father and a professional from one of his day services also attended the training. His father recognised all of Max’s ‘exits,’ demonstrating that Max generalised their use to people external to his staff team.

Discussion

This case highlights how CAT was used successfully both therapeutically with a client with a learning disability and AS and contextually with his staff team. It highlights how instrumental the inclusion of his staff team was in enabling change to occur. The collaboration between the therapist, client and staff team ensured that the ‘exits’ were continually followed and reinforced. It was essential to inform new staff about Max’s roles, procedures, and ‘exits’ in order to maintain his progress.

The benefits were not only a significant reduction of all presenting problems, but also the client’s development of self-awareness and awareness of self in relation to others. This helped him cope more successfully in a world that was difficult for him to understand. It also helped others to understand him.

As these are findings from a single case, caution must be applied in generalising them. However, the results in this case do suggest that it would be beneficial to evaluate the use of CAT with more people who have both AS and LD. It would also be useful to conduct more research to determine the particular factors of CAT that engineer change.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: APA.

Hare, D. (1997). The use of cognitive-behavioural therapy with People with Asperger syndrome. Autism Vol. 1 (2) 215-225.

Jacobsen, P. (2004). A Brief Overview of the Principles of Psychotherapy with Asperger’s Syndrome. Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry. Vol. 9 (4) 567-578.

Kerbeshian, J. and Burb, L. (1986). ‘Asperger’s Syndrome and Tourette Syndrome: The Case of the Pinball Wizard in Tantum, D. (2000). Psychological Disorder in adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome. Autism, Vol. 4 (1) 47-62.

Reaven, J. & Hepburn, S, (2003). Cognitive-behavioural treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in a child with Asperger syndrome. Autism, Vol. 7 (2) 145-164.

Tantum, D. (2000). Psychological Disorder in adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome. Autism, Vol. 4 (1) 47-62.

Full Reference

Murphy, N., 2008. CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually. Reformulation, Summer, pp.26-30.Search the Bibliography

Type in your search terms. If you want to search for results that match ALL of your keywords you can list them with commas between them; e.g., "borderline,adolescent", which will bring back results that have BOTH keywords mentioned in the title or author data.

Related Articles

Talking myself into and out of Asperger's Syndrome: Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) to rethink normal

Victoria, 2015. Talking myself into and out of Asperger's Syndrome: Using Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) to rethink normal. Reformulation, Summer, pp.18-22.

CAT and People with Learning Disability: Using CAT with a 17 Year Old Girl with Learning Disability

David, C., 2009. CAT and People with Learning Disability: Using CAT with a 17 Year Old Girl with Learning Disability. Reformulation, Summer, pp.21-25.

A Case Example of CAT with a Person who Experiences Symptoms of Psychosis

Dr Sara Morgan, 2018. A Case Example of CAT with a Person who Experiences Symptoms of Psychosis. Reformulation, Winter, pp.35-38.

Creatively Adapting CAT: Two Case Studies from a Community Learning Disability Team

Smith, H., Wills, S., 2010. Creatively Adapting CAT: Two Case Studies from a Community Learning Disability Team. Reformulation, Winter, pp.35-40.

Applying Cognitive Analytic Therapy to Guide Indirect Working

Carradice, A., 2004. Applying Cognitive Analytic Therapy to Guide Indirect Working. Reformulation, Autumn, pp.18-23.

Other Articles in the Same Issue

CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually

Murphy, N., 2008. CAT Used Therapeutically and Contextually. Reformulation, Summer, pp.26-30.

Catch up with CAT

Potter, S., Curran, A., 2008. Catch up with CAT. Reformulation, Summer, p.54.

Clinical Implications for the Pregnant CAT Therapist

Knight, A., 2008. Clinical Implications for the Pregnant CAT Therapist. Reformulation, Summer, pp.38-41.

Consent to Publish in Reformulation

Jenaway, A., Lloyd, J., 2008. Consent to Publish in Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, p.7.

Cuckoo Lane

Selix, M., 2008. Cuckoo Lane. Reformulation, Summer, p.6.

How to Enjoy Writing a Prose Reformulation

Wilde McCormick, E., 2008. How to Enjoy Writing a Prose Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, pp.16-17.

Integration of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Understandings

Ruppert, M., Birchnall, Z., Bruton, C., Christianson, S., 2008. Integration of Cognitive Analytic Therapy Understandings. Reformulation, Summer, pp.20-22.

Is CAT an Island or Solar System?

Bancroft, A., Collins, S., Crowley, V., Harding, C., Kim, Y., Lloyd, J., Murphy, N., 2008. Is CAT an Island or Solar System?. Reformulation, Summer, pp.23-25.

Letter from the Chair of ACAT

Westacott, M., 2008. Letter from the Chair of ACAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.3-4.

Letter from the Editors

Elia, I., Jenaway, A., 2008. Letter from the Editors. Reformulation, Summer, p.3.

Metaprocedures in Normal Development and in Therapy

Hayward, M., McCurrie, C., 2008. Metaprocedures in Normal Development and in Therapy. Reformulation, Summer, pp.42-45.

Plugging in and Letting Go: the Use of Art in CAT

Hughes, R., 2008. Plugging in and Letting Go: the Use of Art in CAT. Reformulation, Summer, pp.9-10.

Service Innovation

Jenaway, A., Mortlock, D., 2008. Service Innovation. Reformulation, Summer, pp.31-32.

Silence in Practice

Harvey, L., 2008. Silence in Practice. Reformulation, Summer, pp.11-13.

The ‘Human Givens’ Fast Trauma and Phobia Cure

Jenaway, A., 2008. The ‘Human Givens’ Fast Trauma and Phobia Cure. Reformulation, Summer, pp.14-15.

The Body in Dialogue

Burns-Lundgren, E., Walker, M., 2008. The Body in Dialogue. Reformulation, Summer, pp.18-19.

The Development of the Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation

Parkinson, R., 2008. The Development of the Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation. Reformulation, Summer, pp.33-37.

The States Description Procedure

Hubbuck, J., 2008. The States Description Procedure. Reformulation, Summer, pp.46-53.

Help

This site has recently been updated to be Mobile Friendly. We are working through the pages to check everything is working properly. If you spot a problem please email support@acat.me.uk and we'll look into it. Thank you.